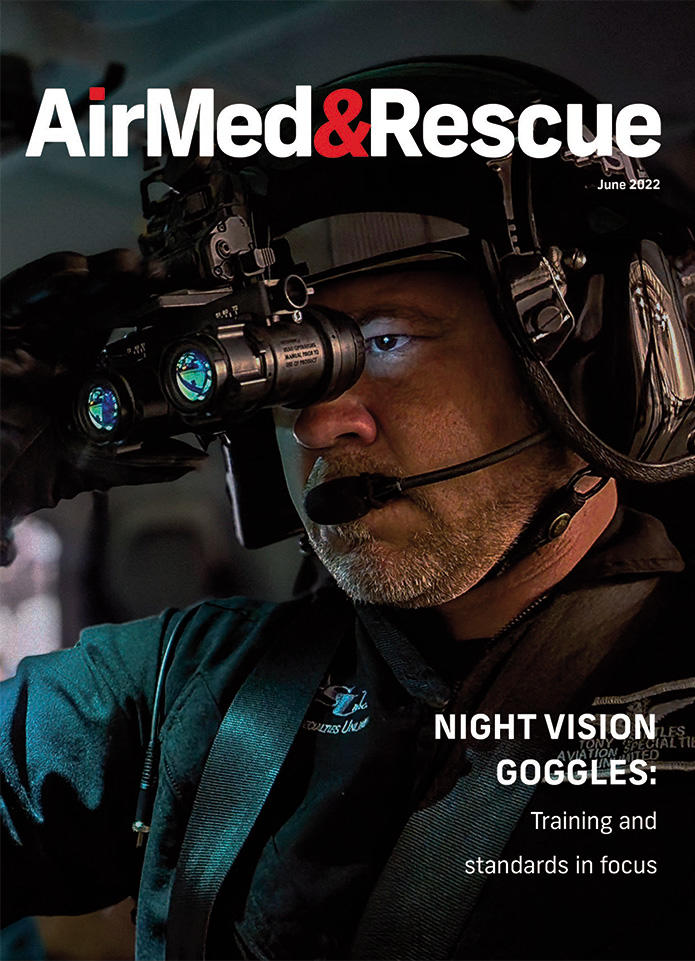

Night vision goggle training: standards and solutions

Mario Pierobon looks at how training on the use of night vision goggles plays a significant role in framing their proper use by crews

Night vision goggles (NVG) are being increasingly used by helicopter as a standard practice for night operations, especially during rescues. Considering that the use of NVGs is safety sensitive, training on their use plays a significant role in framing the proper use of the goggles by crews.

Guidance materials (GM) to European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) safety regulations on air operations (AIR OPS) state that to provide an appropriate level of safety, training procedures should accommodate the capabilities and limitations of the night vision imaging system (NVIS) and associated systems, as well as the restraints of the operational environment.

Most civilian operators may not have the benefit of formal NVIS training, similar to that offered by the military. The GM1 SPA.NVIS.130(f) affirms: “While NVIS are principally an aid to flying under vision flight rules (VFR) at night, the two- dimensional nature of the NVG image necessitates frequent reference to the flight instruments for spatial and situational awareness information. The reduction of peripheral vision and increased reliance on focal vision exacerbates this requirement to monitor flight instruments. Therefore, any basic NVIS training syllabus should include some instruction on basic instrument flight.”

while there is a need to stipulate minimum flight hour requirements for an NVIS endorsement, NVIS training should also be event-based

To be effective, the NVIS training philosophy should be based on a two-tiered approach: basic and advanced NVIS training. According to the EASA GM: “The basic NVIS training would serve as the baseline standard for all individuals seeking an NVIS endorsement. The content of this initial training would not be dependent on any operational requirements. The training required for any individual pilot should take into account the previous NVIS flight experience. The advanced training would build on the basic training by focusing on developing specialized skills required to operate a helicopter during NVIS operations in a particular operational environment.”

In addition, while there is a need to stipulate minimum flight hour requirements for an NVIS endorsement, NVIS training should also be event-based, according to the EASA GM. “This necessitates that operators be exposed to all of the relevant aspects, or events, of NVIS flight in addition to acquiring a minimum number of flight hours. NVIS training should include flight in a variety of actual ambient light and weather conditions.”

The NVIS training requirements in the EASA AIR OPS regulations call for flight crew ground and flight training, training for crew members other than flight crew (the NVIS technical crew members), ground personnel training, NVIS flight instructor training, and training on NVIS equipment minimum requirements.

There are several options available that feature NVG training through various means, typically offering in-house training at their facility and possibly a few more that will send an instructor to the customer’s facility. Tony Tsantles, Chief Flight Instructor and NVG Check Pilot for Aviation Specialties Unlimited (ASU) said: “Many organizations employ their own NVG Check Pilots. ASU offers training in Boise, Idaho, with a variety of terrain and environmental challenges that add nicely to pilot skill and confidence building while using NVGs.”

ASU’s NVG training is delivered academically for either four hours (annual recurrent training) or eight hours (initial training) consisting of interactive, instructor led discussions via PowerPoint

“ASU’s NVG training is delivered academically for either four hours (annual recurrent training) or eight hours (initial training) consisting of interactive, instructor led discussions via PowerPoint”, says Tsantles. “We also offer online recurrent academic training for those who may have scheduling challenges and want to discuss the topics online with an instructor when convenient for the customer,” he says. “Flight training at ASU is conducted in a Bell 206 or Cessna 206 in Boise, Idaho, or in the customer’s aircraft at their facility. Training is always provided by an appropriately rated NVG certified flight instructor (CFI).”

In Australia, there are a limited number of NVIS flight schools, however these appear to meet the demands of the industry, says LifeFlight Rotary Wing Head of Training and Checking Graham Svensen. “The larger users of NVIS have their own flight schools embedded in the company and can provide NVIS qualifications to newly hired aircrew. LifeFlight is one such company doing this,” he says. “There are a few flight schools that offer and conduct training for privately paying clients we are one such organization that delivers training in our AS350 Squirrel. Training is delivered under syllabi approved and regulated by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA), by instructors with NVIS flight training qualifications.”

NVIS training standards are overlaid onto existing VFR performance standards and only additional considerations are typically added when using NVGs, observes Tsantles. “For example, a steep approach in the commercial rotorcraft practical test standards (PTS) references ‘Establishes and maintains the recommended approach angle, (15 degrees maximum) and proper rate of closure’”, he says. “The use of NVGs during maneuvers necessitate the added considerations of maintaining proper scanning techniques to ensure obstacle avoidance and properly judge rate of closure. Use searchlight/landing light to ensure adequate contrast for landing area and to detect obstacles.”

Individual organizations have the ability to adjust their NVG considerations to facilitate performance within standards established in their Company Operations Manual

In Australia, NVG training standards are published by CASA in the Manual of Standards, as part of the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations suite, affirms Svensen. “They are established by CASA with some input from industry. They are revised occasionally, generally based on changes to legislation or industry lobbying,” he says.

The standards established by the regulator – be it EASA, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), etc. - regarding expected pilot performance under visual flight rules (VFR) are still applicable with the NVGs being used, affirms Tsantles. “Traffic pattern standards of maintaining altitude +/- 100 feet and appropriate airspeed +/- 10 knots also do not change with night vision goggles on. Just as other VFR or IFR flight training standards are not often revised, NVG training standards are also not revised,” he says.

Individual organizations, however, have the ability to adjust their NVG considerations to facilitate performance within standards established in their Company Operations Manual or Pilot Training Manual, observes Tsantles. “Of course, they must provide that the overall maneuver still meets the standards commensurate with the ratings held by the pilot (Commercial or ATP)”, he says. “The NVGs as defined by 14 CFR Part 61.1 are ‘an appliance worn by a pilot that enhances the pilot’s ability to maintain visual surface reference at night’. The appliance makes operating in accordance with the standards much easier by having the enhanced surface reference provided by NVGs.”

Often HEMS pilots receive their training in the military before transferring to civilian operation, in this case most users of NVIS have established organic training systems to ensure their flight crew receive ongoing currency and proficiency checks as mandated by legislation, according to Svensen. “Whilst classically, most HEMS aircrew received their training in the military, there is now a much larger contingent of civilian-trained NVIS aircrew in the industry”, he says.

Indeed, according to Tsantles, in both the United States and Europe, there is a significant number of pilots who were not in the military and received their NVG training and endorsement entirely on the civil side. “ASU has trained a great many civil pilots who had never touched a pair of NVGs prior to our qualification training”, he says. “For those who transitioned from the military, civil regulatory entities have already established currency and compliance requirements in most areas we have supported”.

The FAA, for example, requires a civil logbook endorsement to act as pilot in command while wearing night vision goggles in 14 CFR Part 61.31(k), Tsantles observes. “In the same reference, there is a list of required academic training subjects and flight performance tasks to achieve the endorsement. The proficiency of the tasks is repeatedly demonstrated during annual training and evaluations”, he says. “To be considered NVG current, pilots must check with their respective regulatory body, as each may vary with their definition. NVG Currency is listed in 14 CFR Part 61.57(f) for FAA regulated operators in the US. EASA defines NVG currency in SPA.NVIS.130, and they differ quite a bit. Most operators have an approved company operations manual that outline those specifics."

May 2022

Issue

June’s edition of AirMed&Rescue considers sustainability across the industry, communication and asset management tactics during large-scale events, along with night vision goggle training standards.

Mario Pierobon

Mario Pierobon is a safety management consultant and content producer. He writes extensively about aviation safety and has in-depth knowledge of the European aviation safety regulations on both fixed and rotary wing operations. His rotary wing expertise is concerned primarily with specialised operations and the operations requiring specific approval, such as HEMS, hoist operations and performance-based navigation.