Getting a clear picture: procuring the right surveillance equipment for police aviation

Mandy Langfield spoke to police aviators about their choices for onboard equipment that pair crew and aircraft safety with enhancing their aerial law enforcement role

The UK National Police Air Service (NPAS) provides Police Air Support for England and Wales, utilizing a fleet of aircraft that were inherited from individual forces when NPAS was formed in 2013. Each force had previously bought its own aircraft with funding provided by the Home Office. Future fleet replacement will take place through the Police Blue Light Commercial procurement team.

But every police department around the world has a different procurement process; for example, in Alaska, US, aircrews (pilots and tactical flight officers) provide recommendations to leadership regarding equipment needs, as Austin McDaniel, Public Information Officer, explained: “Decisions regarding procurement are generally made at the agency command level. There is an exception if a special procurement need exists, which requires funding beyond budgeted amounts, in which case the state legislature must approve the expenditure.”

Specific equipment for the rotary fleet

Captain Paul Watts, Head of Flight Operations for NPAS, told AirMed&Rescue that its rotary fleet is equipped with a mix of WESCAM MX-10/15 and FLIR Star SAFIRE cameras, while the fixed-wing fleet carries MX-10s alone.

The WESCAM MX-10 is a compact multi-sensor, multi-spectral imaging system for surveillance missions from light aircraft. Its fully integrated weight is 38 pounds (17.2 kg), has a 10-inch (26 cm) diameter and stands 14 inches (36 cm) tall – this small size and low weight reduce the weight and clearance requirements for installation on manned and unmanned airborne platforms. The MX-15 turret can weigh up to 100 pounds (45 kg) with a diameter of 15.5 inches (40 cm) and has a height of 19 inches (48 cm).

The New Zealand Police Air Support is a nationally funded operation that is provided through a partnership with a civilian company determined through a tender process. The Police Air Support contract stipulates the civilian company will provide the aircraft, maintenance, hangarage/office requirements, and pilots (including ongoing check and training). A police spokesperson told AirMed&Rescue: “Each helicopter is crewed by sworn police staff operating as tactical flight officers (TFO) and the three Bell 429 helicopters are outfitted with a modern array of technical equipment including FLIR Star SAFIRE camera systems and Churchill ARS. This partnership provides a dedicated 24/7 Police Air Support Service based in NZ’s largest city, Auckland. Although primarily based in Auckland, the ‘Eagle’ helicopter can be dispatched anywhere in the country should it be required. The ASU crew and senior police are involved in any procurement process relating to the onboard equipment. The airframe provider is responsible for any aircraft equipment relating to continued air worthiness.”

The Police Air Support contract stipulates the civilian company will provide the aircraft, maintenance, hangarage/office requirements, and pilots

In Alaska, the crews have WESCAM MX-10 cameras mounted on their two H125 turbine helicopters. The cameras’ hardware is aided by Churchill Navigation’s Augmented Reality Mapping System.

In New Zealand, both the Star SAFIRE 380-HD and 380-HDc are in use. The system combines HD IR, color, and SWIR spectral information for enhanced results – essential in single video channel downlinks, and 120X magnification optics extend detection range. Laser payloads covertly illuminate and point out targets and determine distance and location, helping TFOs to feed accurate information to the pilot and enabling them to position the aircraft correctly.

The 380-HDc, meanwhile, delivers stabilized HD multi-spectral imaging in a compact, low-profile package that has been designed to maximize ground clearance in rotary aircraft without sacrificing capability and performance. Low power demand of 225W and lighter weight mean that other equipment could be added to the aircraft so that it could also perform multi-mission roles, such as SAR or medevac.

FLIR’s latest upgrade for its 380-HD users is the 380X, which is a hardware, firmware, and software upgrade to support advance image aiding features, as well as reducing operator workload and improving visibility. And, coming in 2021 is another leap forward for camera operators – the use of augmented reality mapping overlays.

© Alaska PD

Training for precise camera operation

Star SAFIRE III, the FLIR’s latest model, features internal navigation for precise targeting, MWIR thermal imager, optional EO color and low-light cameras, and multiple laser payload options.

In the UK, a police crew consists of a pilot and two TFOs. Captain Watts noted: “Training is carried out using NPAS’ in-house team and all TFOs are trained camera operators. Within a crew, one TFO will operate the camera and the other will be mission commander.”

In New Zealand, the training to become a TFO comes first – a nine-month process, and after that, all TFOs are trained camera operators. The police spokesperson explained: “Pilots do not perform the TFO role and vice versa. We consider each position a specialist role.”

In Alaska, meanwhile, TFOs are primarily responsible for camera operations. However, pilots are expected to have familiarity with the system. McDaniel told AirMed&Rescue: “The Alaska Department of Public Safety Aircraft Section emphasizes a crew concept in helicopter operations. Pilots and TFOs have specific roles but are also expected to work closely together in safety and operational decision-making.”

The changing face of camera technology

For Captain Watts, the MX-15 is ‘the most capable camera’, and has been in service for 10 years already. Connectivity is changing the game to improve performance further: “The MX-10 cameras, although not as capable, when coupled with the AIMs mission system in the EC 135 aircraft makes a highly effective search system. The ability to use 4G in flight has been a major step forward and future systems are likely to see even greater connectivity.”

The improvements in technology that have already happened in the past decade or so have rendered today’s cameras invaluable to police aviation units. The New Zealand police spokesperson said: “The high-quality picture, especially in IR sensors has been the greatest advancement. Our previous camera was a FLIR 8500, so it was a significant jump in technology to the Star SAFIRE series. The GPS technology has also provided significant benefits to our operation. This technology now allows integration with our augmented mapping and increased control of the gimbal. The on-screen information is great for providing exact GPS data for providing to our SAR or tactical teams during deployments.”

The improvements in technology that have already happened in the past decade or so have rendered today’s cameras invaluable to police aviation units

© Alaska PD

Looking to the future, when asked what they would most like to see their cameras being capable of, it is evident that artificial intelligence has a role to play. Captain Watts said: “A future system that could ‘learn’ search techniques and differentiate between different targets would dramatically reduce workload and may allow for routine single TFO operations.”

Furthermore, while some search and rescue aircraft can now track and home in on mobile phone signals, most police helicopters are yet to deploy this technology, but it would certainly be advantageous to the teams the air, many of whom respond in search and rescue emergencies.

McDaniel noted: “We have not personally experienced any major developments in the hardware realm in such a short timeframe. The cameras themselves represent a significant capital expenditure for the agency and are therefore expected to have a long lifecycle. However, we have noticed continued advancements in the software that enhances the cameras’ functionality. One example would be motion tracking software that uses machine learning to aid in identifying moving objects (e.g. people or vehicles) in a scene.” He went on to say: “Each iterative step in technology provides some added benefit. For example, the high resolution of our current system is far more effective in locating lost persons than legacy equipment. In looking towards future enhancements, systems that better highlight and track moving objects could be highly beneficial. Additionally, advancements in air-ground data links are expected to provide more capable and cost-effective options for enhancing the situational awareness of ground units/command teams.”

July 2021

Issue

- Adapting skills and aircraft for police multi-mission capabilities

- How UAVs can boost force efficiency

- Selecting the right equipment for police surveillance and SAR

- Interdisciplinary HEMS crew integration in Norway

- An exclusive excerpt from PostFlight: An Old Pilot’s Logbook

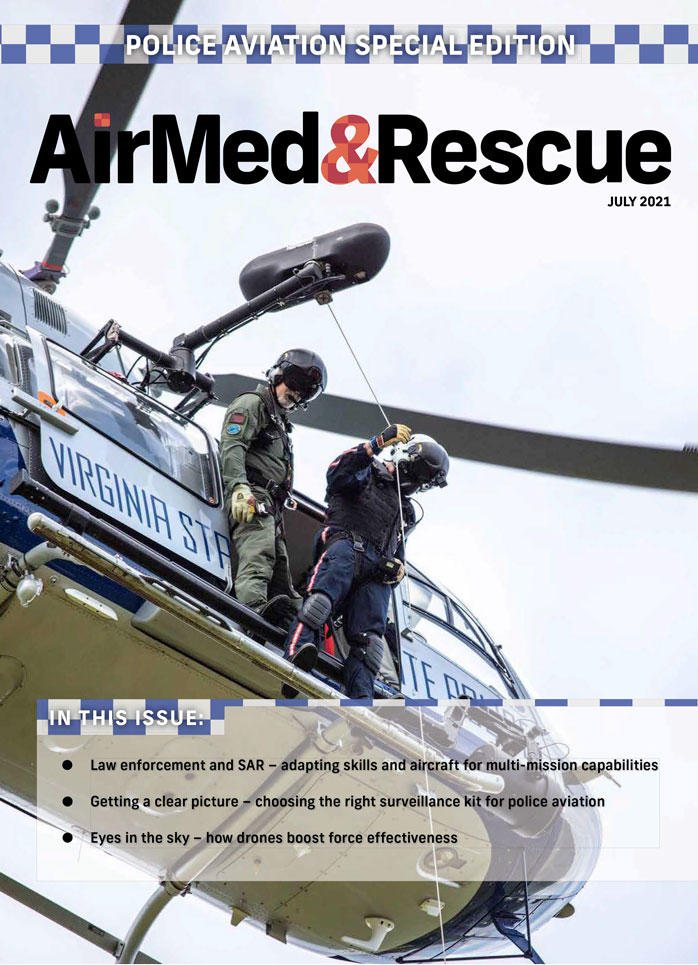

- Interviews: Tab Burnett, Alaska Department of Public Safety; Kevin Kissner, Virginia State Police

- Provider Profile: European Air Ambulance

Mandy Langfield

Mandy Langfield is Director of Publishing for Voyageur Publishing & Events. She was Editor of AirMed&Rescue from December 2017 until April 2021. Her favourite helicopter is the Chinook, having grown up near an RAF training ground!