Eyes in the sky: how UAVs are increasingly used in police search and rescue and surveillance

Mario Pierobon discusses how police forces in North America and Europe are using UAV support to boost force efficiency and effectiveness, and the regulatory obstacles they bring

In recent years, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology has increasingly allowed police teams that were once ground-based to become airborne. UAVs have witnessed a variety of applications by police forces, most recently in relation to the management of the Covid-19 pandemic. At the same time, regulations related to UAV operations are being streamlined and the cost of UAV equipment is coming down. All these factors are encouraging the adoption of UAVs by police forces.

According to Oisin McGrath, CEO of DroneSAR, this has coalesced in a significant increase in operational output at a relatively low cost, particular during Covid-19 restrictions. “Search and rescues (SAR) and missing persons have remained quite high due to the opportunity for people to travel within certain distances from their houses. UAVs provide a simple and cost-effective method to search smaller areas without having to request police air support helicopters. Having livestream capability to a central HQ or the ability to securely crowdsource the search video allows command and control personnel to become involved in searches without being there in person.”

Police use of UAVs

UAVs have a wide variety of law enforcement application, including mapping crime scenes, providing aerial images, and 3D mapping of crash scenes. Master Deputy Matthew Devaney of the Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office, US, stated, “Mapping crash scenes in this manner can help streamline crash scene investigations, ultimately clearing roadways safely and in a timely manner. They also have been used for traffic congesting, such as observing traffic patterns at large scale events – i.e., traffic flows at Covid-19 testing sites, around schools, or during traffic-related crashes, and they help with real-time traffic management and flow.” Devaney continued: “UAVs have further been used for event management at large-scale events, such as at large sporting events or other large gatherings, and can be used during disaster relief, such as tornados, flooding, and large-scale power outages.”

The Santa Rosa Police Department (SRPD), US, uses UAVs for several tasks, but primarily to augment officers on the ground in the provision of community services. “We use them anytime an ‘overwatch’ or ‘eye in the sky’ may assist the officers on the ground in completing a task. These tasks include typical SAR activities, missing persons, crowd management, tactical responses and evidence collection to name a few,” said Micheal Heiser, SRPD Sergeant. “An example of successful UAV deployment includes locating an elderly missing person in physical distress that officers on the ground had been unable to locate. The drone saw a much larger field of view than officers at ground level and found the subject in a field. The UAV pilot was able to direct ground units in and render aid to the individual.”

© Courtesy Ottowa PD

The Queensland Police Service (QPS), Australia, also uses UAVs to assist in operational situations. These include mapping traffic crash scenes, gathering evidence at crime scenes, recordings for media purposes, assisting at the management of sieges, and gaining situational awareness during disaster events such as floods and bushfires. “Our UAV operations are conducted in compliance with the relevant Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) legislation and regulations. These laws and regulations apply equally across all states and territories in Australia,” said a QPS spokesperson.

UAVs have a wide variety of law enforcement application, including mapping crime scenes, providing aerial images, and 3D mapping of crash scenes

The Emergency Services Unit (ESU) of the Ottawa Police Service (OPS), Canada, primarily uses UAVs for search and rescue. “If the SAR team is deployed to look for a missing person in a rural or wooded area, the UAV can cover a much greater search grid with greater speed and efficiency than traditional ground teams can accomplish. The SAR UAVs are equipped with both 30x zoom digital HD cameras and thermal imaging cameras,” said Mike Adlard, UAV pilot and program administrator at ESU OPS. “We use a third 30X Zoom camera that is also equipped with a laser range finder that is able to direct an infrared beam to the ground that tells us the GPS coordinate of the item we are looking at from the sky. This enables us to communicate to ground search teams the exact co-ordinate and they are subsequently able to rapidly navigate to the location to locate the person. Our search teams have embedded paramedics as well so that we are able to immediately administer emergency first aid as required.”

For public order, ESU OPS is currently determining the feasibility of utilizing a UAV for information purposes. “The challenge with this is the balance between flying a large piece of equipment over a large crowd and considering the public safety aspect and the advantage of an aerial view of a large gathering,” said Adlard. “The primary focus in these situations is always public safety, so we have yet to incorporate the use of a UAV in these circumstances.”

UAV regulations

In Canada, the Federal Government has created a system that applies to all UAV pilots depending on the size of UAV that is flying. Adlard continued: “While there are some steps being made to consider the differences between emergency services using UAVs as opposed to the hobbyists, all pilots are essentially bound by the same regulations. One of the challenges that the Government is looking at currently is the ability for an emergency services pilot flying a UAV to fly beyond visual line of sight.”

In Europe, with the recent implementation of the new EASA drone regulations, the training and certification process has become more straightforward, McGrath observed. “Most drone operators will fall into the categories of qualification that allow drone pilots to operate a little closer to people, fly further distances, operate higher weight drones and in some cases fly in previously restricted areas.”

In the US, law enforcement adheres to the same 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) as commercial pilots and air operators. “We follow 14 CFR Part 107 regulations. All of our pilots are Part 107 licensed pilots. The FAA is working to catch up to the growing UAV market, but we are able to function well within the current regulations,” said Heiser.

Adlard observes that often in a rural environment it is difficult to be able to see the UAV in the sky with visual line of sight and cover a large area. “Many UAVs are capable of flying significant distances away but the current regulations prohibit this. This is problematic in an emergency situation,” he said. “Our hope is that the Canadian Federal Government is able to recognize the differences in what emergency services are compelled to do and what the enthusiast should not do. A recognized difference between these two may allow for more flexibility in emergency flights accompanied by increased training.”

While there are some steps being made to consider the differences between emergency services using UAVs as opposed to the hobbyists, all pilots are essentially bound by the same regulations

The national aviation authorities in Europe have their own airspace management rules and these will decide how UAV operators can fly in controlled airspace. This may come with altitude restrictions and/or no-fly zones near bigger airports. McGrath said: “Generally, police forces will require to launch UAVs at short notice and in any area. Agreements would have to be in place between these agencies and the local aviation authorities or air traffic control units. Some authorities will require more specific training to be completed in order for this to occur. Many UAV training schools will be able to assist with this liaison.”

© Courtesy Queensland Police

The cost of equipment

When OPS and the ESU began using UAVs, Adlard recalled, the aircrafts and required payloads were not available on the common market and were, as such, extremely expensive. He added: “In recent years, larger companies have recognized the need and capacity of the professional UAV and come out with UAVs that include longer flight times, superior cameras, safety margins, and efficient deploy ability. That said, they are not cheap, but prices have come down significantly.”

McGrath also recognized that as technology advances, the cost of UAVs has steadily decreased. “Moreover, the cost of additional equipment such as thermal image cameras have also decreased. What was once a military-grade technology has become commercialized, and with this the price will decrease. Nowadays, for a relatively low budget, police forces can implement drone systems,” he said. “Coupled with this, smaller UAVs are becoming ‘disposable’, not meaning that we throw them away after each use, but that if they do land in water or fall from the sky, it is not at a huge loss. Obviously, for more advanced tasks such as long surveillance etc. helicopters will still be required as the mission can easily change very quickly! Flexibility in operations is key.”

The UX factor

The experience of police who are being trained to use UAVs is very positive. “Our staff enjoy piloting the UAVs. The potential of these aircraft continues to expand each year with the development of new technology,” says Devaney.

According to Adlard, UAVs have undeniably demonstrated their advantages. “As we continue to grow our program, we continue to determine additional potential uses. In this vein, we have by far not reached the potential. Moreover, the technology continues to advance, giving us further advantage,” he says.

McGrath observes that it is nevertheless very important that during the UAV training the police units are made very clear of the limitations to these machines. “UAVs are another ‘tool’ for the police officer to use and certainly will not solve all their problems or missions. UAVs need to be implemented into an organizational structure very carefully in order for them to be effective,” he stated. “Proper training, accident reporting, lessons learned, risk management, etc. are but a few pieces that need to be in place before any UAV takes off. Taking a team approach for the entire organisation will result in a much more robust UAV operating system and a much safer and higher operational output.”

The SRPD is continually looking for improved equipment and ways to address its operational needs. “We have plans to expand the use and better integrate UAVs into police responses and to serve our community,” said Heiser. “We definitely have not used them to their full potential. This is mainly because we have chosen to take a phased approach to integrate the UAV as a tool. Our program is relatively new and as it grows and expands, we will continue to add UAVs into how we respond to assist and serve our community.”

July 2021

Issue

- Adapting skills and aircraft for police multi-mission capabilities

- How UAVs can boost force efficiency

- Selecting the right equipment for police surveillance and SAR

- Interdisciplinary HEMS crew integration in Norway

- An exclusive excerpt from PostFlight: An Old Pilot’s Logbook

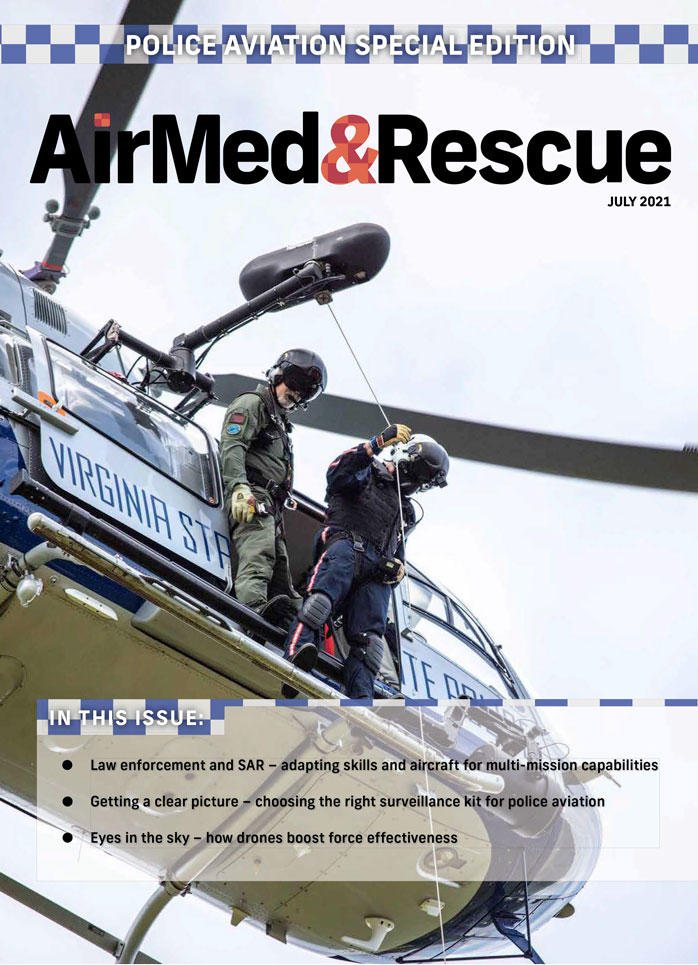

- Interviews: Tab Burnett, Alaska Department of Public Safety; Kevin Kissner, Virginia State Police

- Provider Profile: European Air Ambulance

Mario Pierobon

Mario Pierobon is a safety management consultant and content producer. He writes extensively about aviation safety and has in-depth knowledge of the European aviation safety regulations on both fixed and rotary wing operations. His rotary wing expertise is concerned primarily with specialised operations and the operations requiring specific approval, such as HEMS, hoist operations and performance-based navigation.