Adapting police helicopters for search and rescue missions

Barry Smith discusses how law enforcement teams adapt their aircraft fleet and skills to ensure response readiness when facing the diversity of search and rescue missions

In January 1982, Air Florida Flight 60 – a Boeing 737 airliner – crashed into the Potomac River in Washington, DC after the pilots failed to engage the aircraft’s internal ice protection systems during the snowstorm. The US Park Police Bell 206L LongRanger, Eagle 1, responded to the incident and, using a line attached to the cabin, the crew hovered only a few feet above the icy river to rescue the surviving passengers.

Helicopter-equipped law enforcement agencies from local and national police forces have since been committed to executing search and rescue (SAR) duties as additional assignments. For some, SAR has become a primary mission with dedicated ships and crews. However, this necessitates the same high level of skill and training as other dedicated SAR operators in order to complete them safely and efficiently.

A range of aircraft as diverse as mission parameters

Helicopters used for law enforcement SAR range from light single-engine ships to heavy twins. Outside of the US, most law enforcement agencies that have helicopters belong to national police forces. In Europe, some of the most common ships used for SAR are Airbus H135 and H145 helicopters and their predecessors. In the US, the most common SAR aircraft for police units is the Airbus H125 and its derivatives. With no national police force, single-engine rescue ships are the standard within local and state agencies. However, larger and busier police rescue units are adding Airbus H145s and Bell 429s to their fleets, typically purchasing one for use as the primary rescue ship, while the other single-engine ships are used mostly for law enforcement patrol duties.

A unique source of helicopters for US law enforcement is the Department of Defense: helicopters that have been retired by the military, such as the Bell UH-1 Huey, can be transferred to civilian government agencies at no cost. The recipient agencies modify and maintain them for law enforcement and rescue duties, with many departments installing newer, more powerful engines and transmissions, rotor blades, and other aftermarket equipment to increase their hot and high performance. This results in a very capable rescue ship at a much lower cost than a new aircraft.

Maryland State Police Leonardo AW139 used for EMS and rescue

Getting camera-ready

The most ubiquitous law enforcement equipment for SAR work is the electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) camera systems found on almost all police helicopters. These are critical for search missions where the exact location of the victim is unknown, such as locating missing children and adults with mental health conditions. More recent systems are capable of zooming in on small targets miles from the helicopter, allowing them to search from higher altitudes, which is much safer for the helicopter in the event of a mechanical failure that demands an immediate landing. The high resolution also gives the crew a much better picture of the conditions and possible hazards at the scene and can develop the rescue plan even before they arrive.

Another valuable tool for ships equipped with rescue hoists is an embedded downward-facing high-definition video camera in the hoist housing. The camera images can be sent to a screen in the cockpit that allows the pilot to see what the hoist operator sees, can be recorded for training and mission evaluation, and are often released to local television stations. This is a great public relations tool that can be used to gain public support for maintaining or increasing the budget for rescue equipment.

Rescue rangers

Another rescue technique popular with US police agencies using smaller ships, such as the Bell 407 or MD500/530 series, is short haul. A long rope, up to 250 feet long, is attached to the helicopter by two separate hooks to the belly of the aircraft. A rescuer is then attached to the rope and transported to the victim, who is subsequently attached to the rope and flown a short distance to where the patient can be loaded into the helicopter or passed off to a ground or air ambulance.

Whatever method or helicopter is used, when a unit decides to perform rescue missions, time and money must be dedicated to maintain the necessary skills. This can be especially demanding in areas with a wide variety of terrain and hazards, such as California, which ranges from rivers and lakes to expansive deserts and 14,000-foot mountains.

Some agencies have partnered with local firefighters and rescue technicians to benefit from their expertise, including the California Highway Patrol, which uses Airbus H125s equipped with rescue hoists. They are crewed by a pilot and a paramedic/hoist operator, and each of the eight helicopter bases recruit and routinely train with local rescuers, who are the ones lowered to the victim by the hoist. In the Sierra Nevada mountains, these include mountain SAR experts in climbing and rope rescue as well as avalanche prediction. Lifeguards at park beaches are used for water rescues on lakes and the ocean.

In more rural areas of the western US, several sheriff’s departments have obtained ex-military Bell UH-1 Huey helicopters exclusively for rescue work. Due to the small budgets of these units, some are using volunteers who work full time for fire departments as firefighters and paramedics. This allows the aircraft to be staffed by highly experienced paramedics who can immediately begin advanced life support in the hinterland.

SPONSORED CONTENT - Centum explains the difference having its Lifeseeker device onboard can make to airborne law enforcement units, maximizing the chance of mission success

Our law enforcement clients are using Lifeseeker in an average of 30 to 40 search and rescue missions a year, and say that the main improvement it has brought into their operations is the ability to find missing people faster. In every mission performed with Lifeseeker by our clients, the time needed to find a person was less than one hour, and in some cases even less than 30 minutes, which reduces operational costs for the user.

To make sure Lifeseeker meets the needs of the most challenging missions, we place user feedback at the core of our product development process and have a very close relationship with our clients.

Lifeseeker has been developed according to the operational requirements of a recognized SAR organization. This organization is the early adopter of our product, so they have tested the system in their operational field and have participated in the product’s improvement processes. In fact, many of the upgrades of Lifeseeker and its interface come from that feedback.

Lifeseeker is constantly evolving and that is why we involve all our clients in the product development process. We have a product department in charge of gathering and analyzing customer feedback. Furthermore, we offer an after-sales support in which we solve technical questions from the clients and get feedback from them.

Arizona Department of Public Safety Bell 429 has larger cabin and better hot and high performance than single-engine ships.

Communications systems crucial to success

Of all the skills used during a rescue mission, none is more important than communications. The crews should be using standardized check lists for every type of rescue scenario. Such is their importance, these are frequently laminated and attached to the bulkhead near the hoist controls, and universal words and hand signals are used to prevent misunderstanding. It is only by repetition that the crews can build trust and confidence in each other.

A great benefit to communications that has been recently developed is the wireless intercom. This allows the pilot, hoist operator, and rescuer on the hook to talk with each other without the cumbersome intercom cords that are plugged into receptacles. The rescuer can continue to talk with the crew in the helicopter when they are off the hook and the helicopter moves off while the rescuer is preparing the victim to be moved.

Of all the skills used during a rescue mission, none is more important than communications

Increasingly, law enforcement agencies are seeing the benefit of using external professional trainers to initiate new training techniques and conduct regular audits of tactics, techniques, and procedures. This can be especially helpful when starting high-risk techniques that have not been done before such as night rescues or vertical wall rescues. It is vital that units take a ‘crawl, walk, run’ approach to helicopter rescue, starting with one type of rescue and only a couple of rescue devices. This allows them to master major techniques one at a time and, as crews gain skill and confidence, the training scenarios should get more difficult and complex.

SPONSORED CONTENT - Bluedrop Training and Simulation, Canada, outlines the complex challenges in training police officers for SAR missions and the potential of Simulation-as-a-Service

The principal challenge in developing training solutions for SAR missions is in ensuring high-fidelity physical interactions in a truly immersive environment. SAR operations can be task-saturated in a way that cannot be replicated in a static environment. This extends beyond visual fidelity: complex crew communications, realistic haptic interaction and reactions with the hoist cable, and a changing immersive environment are essential to meet the training needs of skilled operators.

Ideally, crews should be able to train for any mission eventuality, task, or aircraft emergency. But aircraft operating limits understandably differ between operations and training, constraining the variety of missions that can be trained live. This means the first time some crews experience the harsh and variable condition of a rescue is during the rescue itself. Simulation needs to fill this gap and enable high-quality, mission-relevant training that is frequent, adaptable, and accessible.

Bespoke on-site training options

It is imperative that training be brought to the point of need to maximize training delivery and minimize crews being away from essential operations. Training options need to be as flexible as the operators that require it. For that reason, high-fidelity portable options and Simulation-as-a- Service constructs can ensure training is brought to the operation thereby reducing cost, increasing the number of personnel that can be trained and maximizing training outcomes.

Across Europe and the US, virtual and physical helicopter rescue simulators are used to prepare for a greater diversity of training scenarios without the time consumption and cost of using an actual helicopter. In addition, emergencies that could include the need to cut the hoist cable can be run. These facilities are great for developing and practising good communications among the entire crew. Additionally, organizations will run communications simulations using their helicopter on the ground. They power it up and the crew takes their positions and run through all the checklists and talk through a rescue scenario using the precise terminology to ensure familiarity and proficiency during an actual rescue.

Keeping standards high

One of the greatest challenges facing law enforcement and other rescue organizations is the development of standards and accreditation for helicopter rescue. As of yet, there is no single overarching world organization providing accreditation services, but there are numerous working groups and annual conferences that bring together helicopter rescue personnel from all over the world. In the US, the Airborne Public Safety Association (APSA) offers accreditation programs for law enforcement, firefighting, and SAR.

While any helicopter public safety unit can participate, most are law enforcement agencies. If they want to get accredited for SAR, they send in an application. The unit is then sent a copy of the standards for SAR developed by the SAR committee of APSA. The unit then has six months to do a self-assessment to see if they comply with the standards and, in the instance they don’t comply with any of the standards, are given time to do corrections. The unit then is inspected by an assessor chosen by the APSA. The assessor determines if the unit is in compliance with all the standards and submits a report to the commission of APSA. If they are in compliance, APSA then accredits the unit, which is good for three years.

California Highway Patrol uses Airbus H125 for law enforcement, EMS, and rescue

SPONSORED CONTENT - Mario Vittone, General Manager of Lifesaving Systems Corp., spoke to AirMed&Rescue about the unique challenges faced in adapting police helicopters for search and rescue duties

For law enforcement, one of the challenges is creating flotation that can handle the added weight of body armor and armament. Most commercial life vests for aviation cannot handle the added hard weight carried by law enforcement personnel, which is often 20 kilos or more. To stay safe in overwater operations, these operators have to develop gear-ditching procedures, or find a way to increase buoyancy to compensate for the added weight of their kit. Neither solution is easy to achieve.

We receive inquiries every week from law enforcement units who are trying to work out how to take advantage of the new capabilities their helicopters have given them. For example, the hoist of the helicopter is the first necessary five per cent of any hoisting program. Then, units have to identify the equipment, maintenance, procedures, and significant training and flight hours to hone their newly developed skills and keep them current. The helicopter is just the beginning.

Helicopter rescue operations and operators are shifting

Forty years ago, the military was more than 90 per cent of our customer base. Now, they are half. The world of helicopter rescue is growing and shifting continually, and we’ve noticed the increase in activity and capability the world over.

The multi-mission requirements of our police customers often means a decrease in cabin space. Beyond the required harnesses for the rescuers, quick strops are popular rescue kit for law enforcement. They are a lightweight, compact, and inexpensive tool that work well in the recovery of most non-medical rescues. Baskets are a safer and more versatile option but their need for cabin space is a factor for smaller multi-mission platforms.

Rescue missions performed by law enforcement agencies have come a long way since that day on the Potomac River 40 years ago. Ad-hoc rescue missions are hopefully a thing of the past in many parts of the world. Equipment specifically designed for helicopter rescue, backed by constant training using techniques and procedures developed using best practices, has enabled police forces to successfully fulfil SAR missions. However, there is much more work to be done. There are areas of the world where there are no helicopter resources other than law enforcement units that have little rescue capabilities.

July 2021

Issue

- Adapting skills and aircraft for police multi-mission capabilities

- How UAVs can boost force efficiency

- Selecting the right equipment for police surveillance and SAR

- Interdisciplinary HEMS crew integration in Norway

- An exclusive excerpt from PostFlight: An Old Pilot’s Logbook

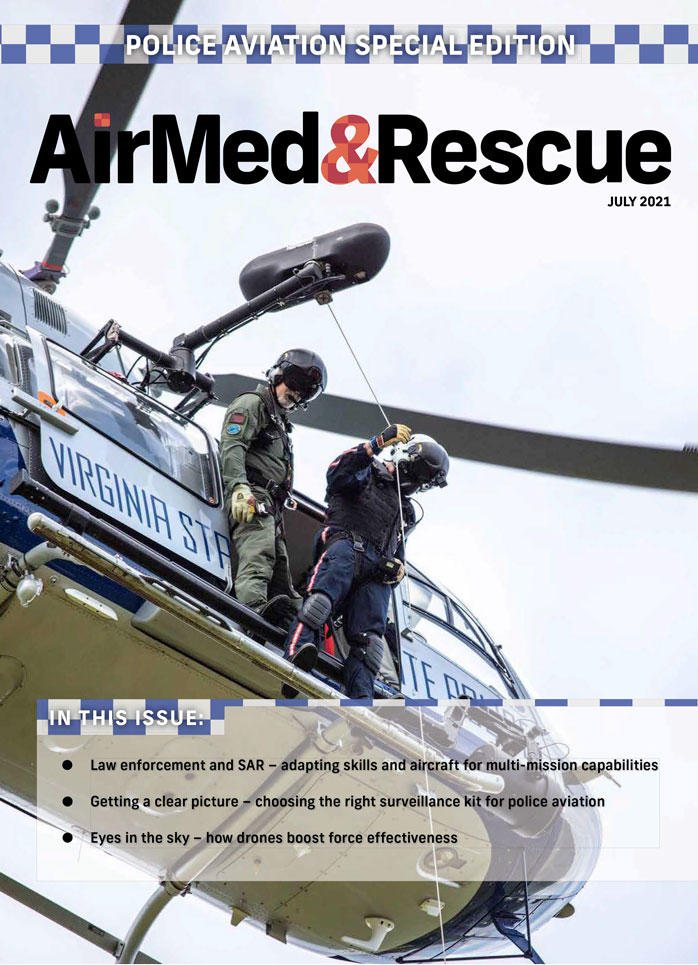

- Interviews: Tab Burnett, Alaska Department of Public Safety; Kevin Kissner, Virginia State Police

- Provider Profile: European Air Ambulance

Barry Smith

Barry Smith has been an aviation and emergency services writer/photographer for over thirty years. He has published over 250 magazine articles and six books. He has also worked in emergency services as a paramedic, volunteer firefighter, and member of search and rescue teams for over 40 years.