Cut the cord: hoisting cable cutting during helicopter rescues

Barry Smith outlines his thoughts on the worst-case scenario during helicopter missions – having to cut the hoist cable with people attached

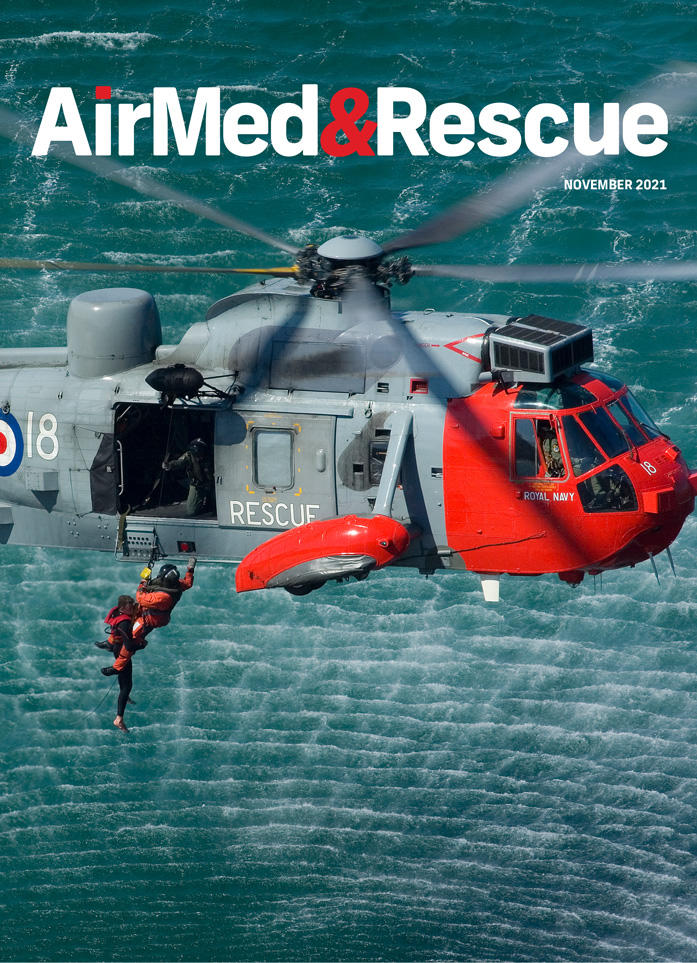

There are few things worse in the helicopter rescue world than having to cut the hoist cable with people attached to the hook. Thankfully, it is a very rare occurrence, but it can have catastrophic results if mishandled. Despite being a low frequency event, it must be kept in mind with every live hoist evolution. Time and effort must be expended on a regular basis to train for this scenario.

Cut in training

“For us, the training aspect for hoist emergencies has three parts,” explained Dave Callen, Co-Founder of SR3 Rescue Concepts. “We have a module that addresses all possible hoist emergencies. The topic that generates the most discussion among the students is cutting the cable. We break it into two scenarios, one is a true emergency that requires the use of the ballistic shearing device and the other is not as emergent – such as the cable being snagged but the aircraft is not in danger. We also discuss case studies of actual hoist emergencies, how they were handled, and what their outcomes were, both good and bad. One crucial aspect that needs to be discussed is the possibility that the crew will have to cut the cable with someone on the hook."

“Psychologically, this could be devastating. But if it means that it might save multiple lives versus the possibility of losing one life, the decision must be made. The crew also needs to discuss this aspect of flying rescue missions and the hazards that are involved,” according to Callen.

The next part of the training scenario takes place in the aircraft on the ground. They take about half a day and run all the students through different possible hoist emergencies on their aircraft. Students simulate cutting the cable with the ballistic device and with a manual device. The important aspect of this training is to show how difficult it can be to actually cut the cable. It can take precious time to find the switch while standing on the skid or even sitting in the door of the cabin, particularly if the helicopter is manoeuvring during an emergency.

The final part is simulating emergencies while flying hoist scenarios. “For example, with a twin-engine ship, during a hoist evolution we will announce a simulated single engine failure and let the crew handle it,” stated Callen. “It is an eye-opener for the students to suddenly have to change focus, quickly make a decision, and physically find the shear switch.”

Pre-plan, pre-brief

A big part of successfully handling any emergency is a thorough pre-hoist brief and good checklist. That checklist includes many of the possible emergencies and what will be done to mitigate them. This can greatly reduce the lag time to respond to an emergency, especially if it might require cutting the cable. Another part of this briefing is for the crew to identify the cable shear switch physically and visually. This also gets the crew mentally prepared for this type of emergency and what will happen. The crew must also have a set command for cutting the cable: it might be shear, shear, shear or cut, cut, cut but whatever the command is, it must be clear and unambiguous.

There are few things worse in the helicopter rescue world than having to cut the hoist cable with people attached to the hook

This also brings up whether it is best to have two pilots during a hoist mission. Many agencies, especially in the US, fly single-pilot. With an aircraft emergency during a hoist evolution, the hoist operator is going to be occupied with the hoist and the pilot with handling the emergency. If there is a second pilot on board, they could probably get to the shear switch more quickly than the other crewmembers.

The other debate centers around using a twin-engine ship for hoist rescues, some of which are capable of flying away from a hover on a single engine. Even if they cannot, under the density altitudes they might encounter, the remaining engine can often be pushed into producing emergency power from between 30 seconds to two minutes, which may be enough to reel in the people on the hoist or do a more controlled descent and shear the cable when the people on the cable are just a few feet off the ground. Many US agencies engaging in hoist missions with single-engine ships are moving to twins for safety reasons, if money can be found in their budget.

Captain Davidson has over 35 years of air transport flight operations, safety, and line flying experience. Davidson currently provides aerospace advisory services to air transport corporate executives and business owners through his management consulting firm, Aerospace Partners, and is Chief Safety Officer at MedHealth Partners.

Far from being restricted to pilot training, Bluedrop Training and Simulation detail how it is bringing the virtual reality landscape to hoisting operations, and how it is meeting the communications challenges within - SPONSORED CONTENT

The potential of virtual reality technology for pilot simulation has been long recognized, but less so for other crewmember roles. What made Bluedrop turn to VR for its Hoist Mission Training System (HMTS)?

Simulation for other crew positions has classically lagged the cockpit but no longer. Bluedrop chose VR because full immersion with less infrastructure and lower cost was required to meet industry training needs.

It’s for this same reason that we are also incorporating extended reality (XR) to further some of the fine motor skills required for cabin management work. Bluedrop believes that training outcomes need to drive the need for simulation not technology. When you mix VR/XR with realistic physical haptics, the sky is literally the limit.

Hoist operation requires both expertise and comfort with the hoist mechanisms, but also strong communication with the winch operator. How does the HMTS replicate these necessary aspects into hoist training?

The winchman is an essential part of the crew in a rescue mission – whether they are in the aircraft, on the hook, or on the ground. Depending on the nature of the operation, we can simulate radio communications between the winchman and the aircraft but more commonly, communication is non-verbal using hand signals or lights for example.

This can be replicated in the simulation environment. Based on the procedures of the operators, we enable the simulation for verbal and non-verbal cuing as operations and equipment dictate. Also, with most rescue scenarios, the pilots can’t see the rescue target once on scene and they rely on the conning or hover trim from the hoist operator for aircraft adjustment. The HMTS fully replicates aircraft crew communications through the connecting of a cockpit training device to the HMTS to truly enable full crew mission training.

Find out more about Bluedrop's Portable Hoist Mission Training System

“As a pilot, I teach other pilots during hoist missions in trees not to hover just over the treetops,” commented Callen. “Even with a strong twin-engine ship, it will lose some altitude if an engine fails. If you hover 40 or 50 feet above the trees and lose an engine, you will have room to drop some altitude as you fly away. If you hover close to the treetops, you will settle into the trees and crash, even if the aircraft had the capability to fly away.

Again, this all goes back to pre-planning and pre-briefing a hoist rescue as you arrive on scene. This is something we are simulating during training with twin-engine aircraft so everyone on the crew sees what happens when one engine is reduced to idle and how aggressive the pilot has to be to fly away safely.”

Cullen continued: “Another way to reduce the time when a helicopter is most vulnerable is to use dynamic hoisting, which I recommend whenever possible. Any time the aircraft can maintain forward airspeed is a tremendous help in dealing with an emergency. The load on the hook is much more stable in forward flight and can reduce or eliminate the load on the hook from spinning. The helicopter is also much more manageable during any emergency with some forward airspeed. I cannot stress enough how much difference an airspeed of just 10 to 15 knots can make in an emergency. It can mean the difference between flying away or having to cut the cable in a twin.”

Hoist-cutting in urban waterways

In an effort to learn more about what happens when a hoist cable must be cut in an emergency, the Los Angeles County, California Fire Department (LACoFD) and Goodrich Rescue Hoists teamed up to create scenarios where they actually used the ballistic shear device to cut some hoist cables. This agency uses two different airframes; the Bell 412 and the Sikorsky S-70 for fire, rescue, and EMS missions. Both are flown with a single pilot and have emergency cable shearing devices on the hoists that use an explosive squib to cut the cable. Additionally, they also carry manual cable cutting devices for non-emergency situations.

“I felt the training was inadequate not only in our unit but in the industry,” explained Michael Dubron, a Firefighter and Paramedic with the LACoFD aviation unit at the time of the tests. “If there has to be any conversation about why and when and how to cut the cable, it will be too late and could lead to a catastrophic event. So, I approached Goodrich to see if we could get some cables and squibs and create some scenarios where we would actually cut cables and see what we could learn.”

In addition to providing cables and squibs, Goodrich representatives attended the training. The scenarios were also videotaped from several angles and locations to use for documentation and future training.

Two different exercises were used during the scenario. One was a swift water rescue with a moving victim in a narrow canal, which is one of the most high-risk rescue environments the LACoFD responds to. In urban areas, the riverbed is lined with concrete and is crossed by many streets and power lines making hoist cable entanglement a very real possibility. It is so easy to be concentrating on the victim and not see a set of wires. Even if you do see them and are able to stop the forward motion of the helicopter, the rescuer on the cable is going to continue being pulled downstream and the cable may hit the wires and require cutting the cable. If it requires a conversation between the pilot and hoist operator, it may be too late.

“We set up some wires across the canal,” Dubron stated. “During the scenario, a rescuer and victim, played by another rescuer, were attached to each other and the hoist cable as we would do in a swiftwater rescue. As the helicopter and rescuer/victim were traveling at the speed of the water, the cable would be encountered, and the cable would be cut. We were using one of our S-70s and, on the first evolution, we learned we had a switchology problem and missed cutting the cable. That was a huge eye-opener. In addition, our procedure is to have the hoist operator standing on the skid or footstep outside the cabin. We found that it was not easy for the hoist operator to reach back into the cabin to find the cut switch.”

Whilst fortunately they have never had to cut the cable in their 10,000+ flight hours, HeliOperations’ Nicholas Chick, Crew Training Post Holder, and Simon Daw, Senior Rear Seat Instructor, detail the essential preparation needed - SPONSORED CONTENT

Training pilots and crewmembers for that most crucial moment – actually cutting the cable – can be taxing, both in mental preparation and familiarizing them with the mechanism to act in the heat of the moment. What approach has HeliOperations had the most success with?

Simon: As the rear crew winch operator, hopefully familiarity and muscle memory will go a long way in an expeditious cut, the moment when any of the crew – although, for the vast majority of times, will be called out by myself at the rear of the aircraft – says cut, cut, which is our executive command to cut the wire. Thankfully, we have never had such an occasion to cut the wire and, until that moment happens, you are never entirely sure if your training has been fit for purpose.

However, we brief this process every single time a winch man descends from the aircraft, and in the many variables each decision depends on – the powers we are pulling and if we are safe with a single engine or otherwise, on the type of surface the winch man is being descended to, whether it is a pitching deck with guardrails or a stable platform on a cliff edge.

What is discussed with the winch man before he is lowered, and what information do the pilot and other crewmembers bring to the decision-making?

Nicholas: The detail of the winch emergency brief is given by the winch operator but specifically with the winch man’s agreement. It is one of the few areas that the pilots have little to no say in.

However, we also discuss on a sortie-by-sortie basis other winch emergencies, such as a jammed or runaway winch, and plan our actions thereon. In this way, these can be ‘practiced’ in a safe environment and we do this on a regular basis. For example, a jammed winch with a winch man dangling 80’ below the aircraft, 40mn from base in a 25kt wind and 5°C external temperature; this kind of situation has many captaincy decisions to consider.

These are a sample of considerations and decisions we take in an aircraft with just a single hydraulic winch. More modern helicopters will have a secondary electric winch, which expands the possibilities of scenarios and solutions.

Simon: Both Nick and I are ex-Royal Navy aircrew, both with approximately 5,500 hours on various types of aircraft. My final years of Royal Navy experience was spent on 771 Naval Air Squadron, based in Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose, where in all that time, we did not have a single occurrence of the winch being deliberately cut.

The impact of Covid

The second scenario involved approaching a confined landing area while lowering a rescuer on the hoist – this time using a dummy – and there was an aircraft emergency that required cutting the cable. The dummy was roughly 10 feet off the ground, which was considered a survivable height.

With the Bell 412, the pilot is the only person that can activate the squib to cut the cable. With the S-70, both the pilot and the hoist operator have cut switches. After the tests, the maintenance department was requested to investigate a change to the 412 so the hoist operator can also activate the squib. It was felt if there is an aircraft emergency, the pilot is going to have his hands full handling that and not have time to make the decision and actually cut the cable.

Dubron created a class on their tests and the issues that arose and presented it at the Goodrich Hoist Users Conference at HAI in Anaheim, CA, in 2019. They presented the class to the Airborne Public Safety Association Rescue Summit held at HAI as well. This reached an international audience, which was its intention. One of the goals of the tests was to present the findings as widely as possible. Dubron said they got invitations from all over the world to present their findings. Unfortunately, Covid-19 hit right after the conference, but Dubron hopes to be on the road when international travel is normalized.

“One of the things we want to concentrate on is creating a culture of learning from other units,” explained Dubron. “We have a very active rescue program that is considered one of the best in the US. But, we can still learn from other operators and we want to pass that along. For the sake of safety, everyone needs to check their egos and be open to new techniques, procedures, and equipment.”

October 2021

Issue

- The demand for automation reveals its shortcomings meeting the human factor

- How virtual and augmented reality meets the needs of SAR/HEMS training

- Keeping critical communications infrastructure live during Hurricane Ida

- How logistics is the critical challenge of neonatal air transport

- The latest SAR equipment that pairs innovation with affordability

- Interview with Rob Pennel about the EASA South East Asia Partnership Program

- And more

Barry Smith

Barry Smith has been an aviation and emergency services writer/photographer for over thirty years. He has published over 250 magazine articles and six books. He has also worked in emergency services as a paramedic, volunteer firefighter, and member of search and rescue teams for over 40 years.