How to make sure your hoist cable doesn’t fail during an airborne rescue mission

James Paul Wallis examines what can go wrong with neglected helicopter hoist cables and the signs winchmen need to watch out for

As the rescue swimmers rise to the safety of the helicopter, the cable from which they’re suspended begins to unravel. Veteran Ben Randall judges that the frayed cable isn’t strong enough to hold both him and rookie Jake Fischer, so he unclips and falls into the dark waters below. This nightmare scenario was, thankfully, filmed in front of a blue screen for Hollywood movie The Guardian and no actors were harmed, but it illustrates how important the hoist cable is in the helicopter rescue system. Beyond the loss of a rescuer or casualty, past incidents have shown that a cable that separates can be a danger to the whole crew if it whips up and impacts the main or tail rotor. Despite all the technology onboard an aircraft, the condition of just a few strands of wire is vital to mission success and safety.

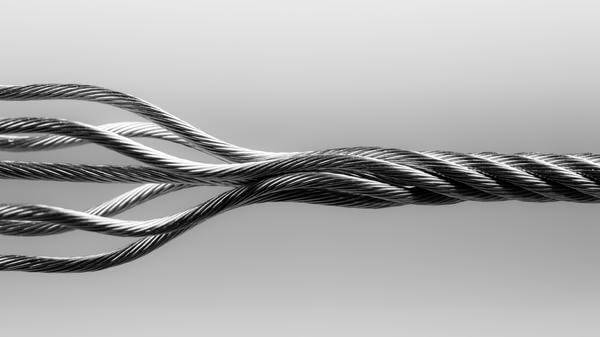

A typical hoist cable is a stainless-steel rope attached to the hoist at one end and a hook at the other. Individual wires are twisted into strands, and the strands are twisted to make an inner core and an outer wrap. Together, these wires share the load of rescuers and casualties and must withstand being wound and unwound from hoist drum and exposure to sometimes harsh environments. Any defects can lead to a reduction in strength and premature failure.

Care of cables includes inspection, cleaning and lubrication, depending on the cable type, all following guidelines laid out by the original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

Inspections

Cables are regularly inspected by operators and repair centres. Swiss air rescue service Rega, for example, inspects its hoists and cables every month or after one operating hour. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) uses authorised contractors alongside its own technicians to maintain its cables. As well as daily checks, there are more detailed inspections based on the frequency of usage. At Travis County STAR Flight, maintenance staff inspect the cable after every use as soon as is practical. Casey Ping, who spoke to AirMed&Rescue just ahead of his retirement as Programme Director, said the organisation goes beyond the inspection schedules prescribed by OEMs: “At a minimum, we follow the OEM guidelines. We also perform additional inspections, both in frequency and type.”

At Priority1Air Rescue (P1AR), Manager SART/TAC Adam Davies detailed that both hoist operators and rescue specialists should take the time to do user level inspections of their cables after hoisting flights to ensure they are still in good condition. Common signs of damage or excessive wear include flattening, bends, kinks, broken strands and ‘milking’, said Davies, as well as bird caging, where the outer strands stretch and open out. P1AR crews use a cable dimensional checker tool in the field to identify any necking or bulging that will need further investigation.

Air Rescue Systems, which sells hoisting equipment and cable care tools, advises users to also check for off-coloured deposits or powder that may indicate superficial or internal corrosion, as well as necking (sections of narrowed cable that indicate broken internal strands).

Inspections should be both visual and tactile, said a representative of hoist-maker Breeze Eastern. And there are more hi-tech approaches such as MagSens, a non-destructive inspection system that uses magnetic flux leakage to spot potential defects in the cable, which is offered by Zephyr International. Michael Mitchell, President of Zephyr, explained: “The MagSens provides a simple repeatable method to inspect the cable and it provides a means of standardising the inspection, so anyone with basic training can inspect the cable better than a trained individual, because it can sense and detect damage on the inside of the cable.”

A damaged cable is best replaced, not repaired, said Davis: “There was a time when, if a hoist cable was damaged and it was not too far above the hoist hook, they would consider, based on the type of damage, cutting the cable and re-swaging the end, but, fortunately, that does not happen anymore. For the most part, the industry operates a zero-tolerance policy regarding hoist cables. Meaning if they are damaged in any way, they are replaced.” However, Mitchell told AirMed&Rescue that his testing shows that if properly installed, the connection to a new ball end is stronger than the cable itself.

One complexity of performing an inspection is that the cable should be kept under tension as it’s unwound and rewound onto the hoist drum. Zephyr International’s maintenance stations include capstans that keep the cable under tension while being wound onto a drum. Air Rescue Systems’ Cable Buddy offers a more manual solution, comprising a pulley attached to the helicopter’s floor anchors or skids that allows a crew member attached to the cable to apply tension by leaning back as they walk away from the aircraft.

Cleaning and lubrication

Other than checking for damage, the other main aspects of cable maintenance are cleaning and lubrication. A spokesperson for Breeze Eastern commented that users should pass the cable through a clean cloth in order to remove debris or other contaminants, and should also perform a fresh-water rinse if the cable has been exposed to salt water or high-humidity environments.

Adam Davis commented that lubrication is typically performed by the maintenance department during their maintenance and inspections on the hoist. A common and simple method, he said, is to slowly reel the cable in while letting it pass through an oiled towel in your gloved hand. Rega uses a similar approach, a representative explained: “We use a lint-free cloth, put oil on it and, during reeling in, we lubricate the cable. We refresh the cloth every seven metres with new oil so that the whole cable is lubricated thoroughly.”

Zephyr’s RHGSE mobile cable maintenance station features an assembly that uses compressed air to dry the cable as pads clean it and apply lubricant (if required) as the cable is retracted into the hoist, explained Mitchell.

The RCAF is among operators whose cable maintenance routines do not include lubrication due to the type of cables used, a spokesperson confirmed. Breeze Eastern told AirMed&Rescue why its guidelines do not include lubrication: “The oils within the cable are intended to remain within the interior for the life of the cable. In general, our position is that no additional lubricant should be added to the cable on top of the existing lubricant, especially to the cable’s exterior, since doing so may interfere with the action of the tensioning system.” There are, however, circumstances when lubrication may be appropriate, the representative added: “Some usage, cleaning, and maintenance processes end up stripping the lubricants from the cable’s interior and re-lubrication may be considered as anti-corrosion measure. In this case, thin lubricants which are applied in contact with the cable should be removed from the cable’s exterior with a clean cloth.”

As for the choice of lubricants, for the cables that come with Goodrich hoists, use of OEM-prescribed lubricants ‘is a necessity’, said Marty Sezack, Manager of Aftermarket Technical Services, Hoist and Winch, at Collins Aerospace, which owns the Goodrich brand. He continued: “Off-the-shelf products such as WD40 may aid in water removal and cleaning, but do not provide the level of lubrication required to attain full cable life.”

Mitchell commented: “The lubricants used are many but the most common is a thin film corrosion preventative, many commercially available products are available. I prefer the thin-filmed CPCs over the turbine oil that Goodrich calls out.” He explained that the oil penetrates the cable through capillary action, displacing any water inside.

Service life and replacement

Even if no damage is identified, the cable will need to be replaced when it reaches the end of its service life. The OEM sets the replacement criteria, explained Ping, which is usually a combination of age and usage cycles. Davis gave ballpark figures of 1,500 cycles or 55 hours of actual use. In Davis’ experience, it’s rare that a cable lasts to the end of its life cycle, though: “They are most commonly replaced due to common wear that occurs from regular hoisting.”

Ping added: “Since it is a life safety product, we may replace in any significant event (shock load, cable strike and so on) without meeting replacement criteria. It is a small price to pay for confidence in the equipment.” A shock load is a rapidly applied dynamic load that can damage a cable, even though it could safely take the same load if gradually applied (a static load). This can occur if, for example, the cable suddenly gets caught on the skids.

Cables installed and delivered with new hoists are properly tensioned and conditioned by the manufacturer, noted Sezack. If a cable reaches the end of its life and is replaced, the new cable should be conditioned following the same procedure. Using the term cable ‘seasoning’, Davis explained that the cable must be tightly wrapped to the hoist drum.

In-flight emergency

Returning to our example of Kevin Costner’s heroics in The Guardian, what is the procedure if a cable fails during operations? Crews on a helicopter with a dual-hoist system can simply switch to the backup, but for those without that luxury, Davis explained that one option is to cut the cable above the damaged area and apply a splice, which traps the end of the cable and creates a temporary attachment point. This can be a traditional slotted plate or a more advanced option such as the Quick Splice offered by Lifesaving Systems. Davis said: “[This] allows you to … perform one recovery to get your rescuer back to the helicopter. This is, however, considered an emergency procedure, so if there are other safer or more viable options for that recovery, those options should be exercised first.”

Prevention

Cable care is a matter of flexibility and vigilance. Cable servicing, both care and conditioning, should be driven by a planned programme, but this should adapt to any changes in operational tempo, said Sezack: “Operational safety driven by a regular inspection programme, inclusive of post-mission inspections, remains the best course of action … these inspection and maintenance practices also help assure full operational life of the cable and thus a lower cost of ownership.”

As a final thought, let’s remember that prevention is better than cure. Davis highlighted that good cable management extends to the care you take during missions: “When hoisting you want to ensure that you are managing the cable with an expert level of finesse to ensure that the cable is not contacting surfaces that it should not, as well as ensuring that you are not shock-loading the cable.”

June 2019

Issue

In this issue:

Military SAR content:

Spotlight: Italian Air Force’s dedicated SAR unit, the 15th Wing,

Review of the operations that occurred during Hurricane Florence by a member of the US National Guard

Royal Canadian Air Force interview - what does it take to be a SAR Tech?

Medical Insight: The physiological effects of winching

The importance of cable care

Review of Rotorcraft Asia

James Paul Wallis

Previously editor of AirMed & Rescue Magazine from launch up till issue 87, James Paul Wallis continues to write on air medical matters. He also contributes to AMR sister publication the International Travel & Health Insurance Journal.