High-rise helicopter rescues

Barry Smith investigates the unique challenges of helicopter rescues when you’re surrounded by high-rise buildings

With over 750 high-rise commercial and residential buildings, the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) has developed a sophisticated helicopter response plan for fires in these structures. The LAFD has a fleet of seven helicopters, five Leonardo AW139s and two Bell 206s. Their primary role is to fight wildland fires.

Response by numbers

“The LAFD dispatch center has very specific response algorithms for fires in different types of buildings,” explained Scot Davison, LAFD’s Chief Pilot. “Air operations is automatically dispatched on any second alarm at a high-rise building. A second alarm is called by units at the scene that determine more resources are needed. A minimum of three helicopters respond. One fills the role of helicopter command, known as the Helco. The Helco is responsible for airspace management over the fire for any helicopters that respond.”

Once the Helco is on scene, he begins to communicate with the incident commander (IC) on the ground to develop a plan for how the helicopters will be used. Do people need to be evacuated from the roof, are any hoist rescues going to be needed, will the helicopters transport firefighters and equipment to the roof? The Helco can also describe the fire situation by determining the exact location of the fire, how and where it is spreading, and determine if there are any people trapped near the fire or on other floors.

“If it is determined that the helicopters will be used to evacuate people from the roof, the first hoist helicopter will insert one or two flight paramedics, who are also firefighters, onto the roof,” stated Davison. “They will control and triage the victims on the roof. They gather all the victims together, shelter in place and determine if any of them need to be immediately removed due to injury or illness. The decision to evacuate by helicopter is driven by how the fire is progressing and if the structural integrity of the building is compromised by the fire. The number-one option is to have the victims shelter in place with the flight paramedic / firefighters. This would be a location on the roof away from the heat and smoke of the fire. Once the fire is under control, the victims can walk down the stairwells. If it becomes unsafe, then the incident commander will call for helicopter evacuation in co-ordination with the Helco.”

Specific criteria to be met

The first aircraft, often one of the Bell 206 Jet Rangers, will be the Helco. The second ship will be the hoist rescue aircraft. It will insert the flight paramedic / firefighter onto the roof. The third helicopter will transport the Airborne Task Force, which consists of four to five firefighters, and their equipment, to the roof of the building. To place this team on a roof, there must either be a helipad on the roof, or the helicopter can hover no more than three feet above the roof. If these criteria are not met, they will not be used. Once on the roof, they will be directed to perform specific tasks by the IC. They typically do not fight fire from above. They would be doing search and rescue for victims on the floors above the fire, and reporting on conditions within the building. Any victims found would be escorted to the roof and turned over to the flight paramedic. If a high-rise incident required more helicopters than the LAFD has, there are several other sources of rescue helicopters within the area.

No limits on adaptability when it comes to Hoist mission training |Sponsored content|

No limits on adaptability

Bluedrop’s unique Hoist Mission Training System uses the latest technology to ensure that there is no limit to the complex operating environments on which users can train, according to Barbarie Palmer, Senior Director of Business Development for Bluedrop

Able to provide geotypical terrain capabilities as a stand-alone product or integrate with a front-end training device for full crew mission rehearsal, you can virtually train for a myriad of operating conditions including:

- Time of day – day/night/NVG

- Environment – wind, sea state, decreased visibility (brown out, fog, rain)

- Terrain – over land, over water, confined area, complex hoist target, urban / built up

- Procedures / malfunctions – TFZ, snagged cable, hoist overtemp, run away cable, cable cut, double hoist, sling load

- Equipment – Stokes litter/guideline, horse collar, double lift, rescue basket and more.

Currently, there are many things for which operators cannot train outside of a live environment – either because there has historically been no means of realistically simulating it, or because the safety parameters on live training prohibit it. Bluedrop believes that much of a SAR environment is already high-risk, and that it is our responsibility to ensure that high-fidelity training limits that risk where possible.

Once it has been determined that a helicopter evacuation will be done, a pre-determined casualty collection point will be created on the ground to offload the victims. Paramedics and ground ambulances will be staged there to care for and transport the victims to the hospital.

Typically, they only carry about one hour of fuel in the AW139 helicopters. This allows them to maximize performance and load capability for firefighting and hoist rescue missions. For a high-rise incident, they send one of their fuel trucks to a pre-designated helispot near the incident so the helicopters can quickly refuel when necessary.

State arrangements differ

To place this team on a roof, there must either be a helipad on the roof, or the helicopter can hover no more than three feet above the roof

With a population of over two million, King County, Washington, which includes the city of Seattle, has no fire department with helicopters. However, the King County Sheriff’s Department, as well as neighboring Snohomish County Sheriff, use helicopters to perform rescue missions.

“Snohomish and King counties have been working together on rescue responses for almost 15 years as part of the Northwest Regional Aviation organization,” stated William Quistorf, Chief Pilot for the Snohomish County Sheriff's Department. “This is a group of helicopter units in Washington State that includes local, state, federal and military agencies that work together to respond to local and regional emergencies. Both agencies operate Bell UH-1H Huey helicopters equipped with the same rescue hoist.”

The Seattle Fire Department established an Aviation Special Operations Team (ASOT) to work with rescue helicopters. They began with training these firefighters on how to work around and in the helicopters. They then progressed to a fire department training tower, which was used to simulate a high-rise building for hoist operations. They were also trained in how to establish a safe landing zone and how to assemble and attach sling loads to the helicopter. This technique is used to transport rescue and firefighting equipment to the roof of a high-rise building. The team currently has 12 members.

In 2011, the Seattle FD arranged for training on a 50-story building in downtown Seattle. Here, they worked out a set of common procedures for the helicopter and the ASOT members. Complete evolutions were done with firefighters hoisted down to the roof, firefighting equipment transported via sling load, and removal of the team via the hoist. They also trained on hover step procedures where the helicopter is hovering about a foot off the roof and the firefighters exited and entered the cabin. Since then, the helicopters and the fire department team have continued to do quarterly proficiency training on these high-rise skills.

Collins Aerospace Goodrich share their insights on Hoists for high-risk environments |Sponsored content|

High-risk, high-reward

Collins Aerospace Goodrich hoists are used around the world in higher-risk environments for search and rescue operations, where high-performance equipment is mandatory

All Collins Aerospace Goodrich® hoist designs have been tested to MIL-STD-810 and/or DO-160 test requirements for hot / cold temperatures, explosive atmosphere, salt, fog, EMI, etc. they also undergo a 5,000-cycle endurance and specific damage tolerance tests to ensure that the customer does not experience issues during rescues.

We’re constantly engaged with our customers – both online and in person (as COVID allows) – and always take their feedback to heart. Customer feedback has led to incremental design modifications to each of our hoist models in response to the ever-evolving operating environment and mission.

Supporting our customers is an important part of our mission and we provide maintenance repair and overhaul (MRO) services at a number of MRO facilities and Authorized Repair Centers worldwide.

Reflecting on real-life use

We work with multiple organizations that train using our equipment, either as part of a larger organization or as a separate, training-focused organization. Over the years, multiple improvements have been made to hoists, either driven by customer feedback or regulatory requirements.

In 1995, we developed the first hoist with a 290’ cable length as requested by a Japanese customer for mountain search and rescue. We also worked closely with dedicated SAR operators to optimize the performance of the hoist in maritime situations, where faster and more precise control was requested by operators when rescuing in large waves. We have worked to add specific controls for the operator, including searchlight and helicopter hover/trim from the operator pendant, which enable a more efficient rescue operation as well.

We have also developed specific configurations for military operators, whether a rear mounted configuration; integration of a fast rope attachment point, a dual hoist system with dual cable cutters and HUMS system; or optimizing the design for extreme low-temperature operation.

“As with any helicopter rescue mission, we would do a reconnaissance of the building and the surrounding area,” commented Quistorf. “One of the first things we want to know is what are the winds doing. The winds act much differently in an urban high-rise environment than in the mountains. In the mountains, we well know how the winds will react based on the topography. With multiple high-rise buildings in an urban setting, the winds bounce and swirl around the structures and are very unpredictable. You can get up and down drafts and burbles over the tops that can make a steady hover very difficult. But, if we get too high above the roof to avoid the turbulence, it can also make hovering difficult due to the lack of visual references.”

Unique obstacles

The next thing to consider is what types of obstacles are located on the roof. Many buildings have antennas, cell phone towers, and air conditioning units that must be avoided. Very few have helipads on the roof, which mean a hover step maneuver to unload and load is necessary. They also look at the buildings surrounding the incident and assess access to nearby rooftops. They would rather move victims from a building to another roof close by, than fly all the way to the ground. In addition, in a built-up downtown district, the closest place to land could be some distance from the incident, increasing the time between loads.

If they are not able to land or do a hover step to remove the victims, hoisting takes a lot of time if there are many victims. In addition, after picking up three or four people, they would have to go someplace to unload them. Quistorf therefore looked at other rescue platforms that could carry more people and be loaded rapidly. They decided to use the Airborne Tactical Extraction Platform (AirTEP) made by Capewell Aerial Systems. This platform is attached to the cargo hook with a 15 to 25-m rope. A firefighter with a radio would be on the platform. It would be placed on the roof and five to six victims at a time could be rapidly loaded, secured and removed from the building. Large groups of firefighters can also be moved onto the roof.

“One of the most important roles for the helicopters at a high-rise incident is to provide information about the fire to the incident commander,” stated Ron Mondragon, an Operations Deputy Chief with the Seattle Fire Department. “Several of the law enforcement helicopters are equipped with microwave video downlink capability for their camera / FLIR systems. Our department has several handheld video receivers that can connect with the helicopter’s downlink system. This gives the command team a bird’s eye view of the fire. FLIR is a valuable tool for determining where the hottest part of the fire is located and where it is spreading. It also allows the command team to keep track of the firefighters in the building.”

“In addition, the AirTEP is an excellent way of transporting firefighters onto the roof. They need no special training, as one member of the ASOT will also be on the platform to make sure they are secured properly and safely get on and off the device. The decision to remove victims by helicopter needs to be made early in the incident. We have found that as a fire progresses and generates large amounts of heat and smoke, it interferes with helicopter operations. You also have the be aware that rotor downwash can affect the fire behavior.”

Regulation changes on the horizon?

“In the future, we see the possibility of using UAVs to gather information at high-rise fires, which would eliminate the noise and rotor downwash of a full-sized helicopter,” pointed out Mondragon.

The city of Seattle has never required emergency helipads as part of the building code for high-rise buildings. Mondragon said they are working with their Fire Marshall’s office to designate emergency helispots on the roof of high-rise buildings. They are looking for a 20-ft diameter area that is clear of obstructions where the AirTEP could be safely landed. These will be designated by a circle with a red ‘R’ painted in the middle. So, an expensive helipad, the construction of which is heavily regulated, does not have to be placed on a building. They would like to see this as part of the fire code, but it is not currently mandatory.

While many high-rise fires have been attended by helicopters around the world, it is often an ad hoc, unco-ordinated operation. These type of low occurrence-high-risk operations need planning and input from all the responders before they happen. Even regions with no dedicated fire department helicopters have shown they can develop an effective aerial

January 2020

Issue

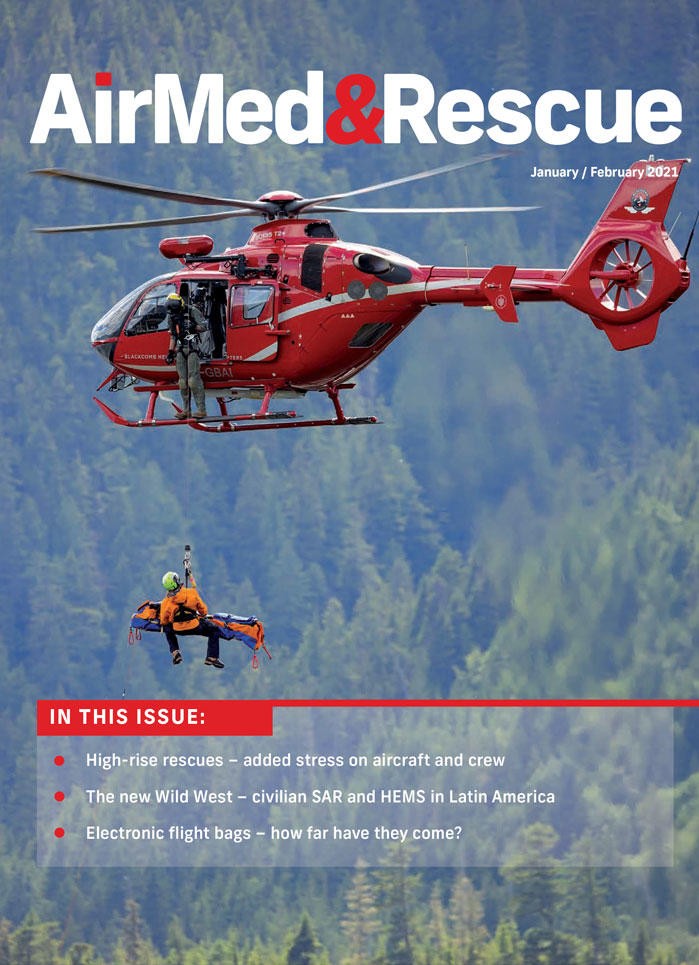

In this issue

- High-rise rescues: added stress on aircraft and crew

- The new Wild West: civilian SAR and HEMS in Latin America

- Electronic flight bags: how far have they come?

- Interview with Dr Duncan Bootland, Medical Director, AA Kent, Surrey Sussex

- Research into point of care tools for diagnosis

- EURAMI accreditation during Covid-19

Barry Smith

Barry Smith has been an aviation and emergency services writer/photographer for over thirty years. He has published over 250 magazine articles and six books. He has also worked in emergency services as a paramedic, volunteer firefighter, and member of search and rescue teams for over 40 years.