Three Little Pigs – or, how hard work and dedication pay off

In the third of four features, aeromedical pilot Mike Biasatti stresses the importance of being the master of the airframe you’re piloting, while demanding of yourself an expert grasp of knowledge so that if things do go wrong, you have the understanding of what’s happening and the confidence of how to react

The age-old story of The Three Little Pigs as told by James Halliwell-Phillipps is one I heard as a child. Just recently while sitting with my young son, it popped up on the cartoon channel and I started thinking of parallels in my aviation career and the lessons this old fable might contain.

This is a tale about three pigs who build three houses from different materials. A big bad wolf blows down the first two pigs’ houses, made of out of straw and sticks respectively, but is unable to destroy the third pig's house, built with bricks.

The primary moral lesson learned from the three little pigs is that hard work and dedication pay off. While the first two pigs quickly built homes and had more free time to play, the third pig labored in the construction of his house of bricks.

Fortune favors the well prepared

In life – and particularly in aviation – fortune favors the bold, but to an even greater degree it favors the well prepared. To be well prepared takes a commitment to be a life-long learner, particularly when it comes to the operation of an air medical helicopter.

Studies show that when our brain is constantly switching gears to bounce back and forth between tasks – especially when those tasks are complex and require our active attention – we become less efficient and more likely to make a mistake. This might not be as apparent or impactful when we’re doing tasks that are simple and routine, like listening to music while walking, or folding laundry while watching TV. But when the stakes are higher and the tasks are more complex, trying to multitask can negatively impact our lives – or even be dangerous.

Aircraft checklists are a pilot's best friend to ensure proper action is taken during something as routine as pre-flight, engine start, cruise check, but equally or perhaps to an even greater degree are the Emergency Procedure Checklists. You should:

Land Immediately – Urgency of landing is paramount. Primary consideration is survival of occupants. Landing in water, trees, unsafe area should be a last resort

Land As Soon As Practical – The duration of the flight and landing site are at the discretion of the pilot. Extended flight beyond the nearest approved landing area is not recommended.

Stop, confirm, act

One of our flight nurses shared a scary experience they had on a night flight with a patient onboard. In this case, the aircraft was a visual flight rules (VFR) Bell 407. The ceilings were deteriorating and the crew noticed the helicopter in a gradual descent. Handing the sectional chart to the nurse in the back, the pilot asked him to locate their position and steer them away from any towers in the area. As the pilot focused more and more on staying out of the clouds, he unintentionally pulled in too much power (raised the collective) for a period of time that exceeded the transitory range for the five-minute limit on engine torque, and a subsequent ‘Check Instrument’ caution light illuminated on the aircraft’s caution and warning panel (CWP). At that point, the pilot asked the medical crew if they knew what that meant and when they didn’t, he handed them the Rotorcraft Flight Manual and asked them to look it up in the Emergency Procedures section.

The cause of the fault was realized in time and the aircraft and crew were able to successfully complete the transport, but not before nearly entering instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and then descending well below a minimum safe altitude. It served as a sober reminder to me that knowledge of the aircraft, and particularly anything on your caution and warning panel, deserves your time and attention prior to ever lifting off. What could have been a simple correction, coupled with other distractions in a stressful scenario, could easily have had a different outcome.

Helicopters, especially single-engine helicopters with no autopilot and no co-pilot, require hands-on operation, such that trying to look through a bulky aircraft manual to find a procedure for a caution or warning light is impractical. Every operator will have its own policy and expectation for their pilots, but a very good general rule of thumb is that any caution/warning light that the emergency procedure indicates a ‘land immediately’ or a ‘land as soon as possible’ should be a procedure that you know verbatim, as your attention will be primarily on getting the aircraft safely back on the ground. When and if time permits, once you’ve completed the called for action, back it up with the checklist.

Always confirm what you’re seeing.

Always confirm what you’re seeing. I flew with an experienced captain when I was flying offshore and he told me the first thing you do in an emergency is nothing. Stop. Confirm. Act. It’s happened before where pilots of twin-engine aircraft have responded so quickly under the stress of an engine failure that they accidentally rolled off the good engine. Stop. Confirm. Act. Then always back up any action with the checklist.

Currency and proficiency

There can be a large gap between a pilot’s currency and a pilot’s proficiency. In the US, an air medical helicopter pilot who operates a VFR helicopter receives annual training and testing in each aircraft model he or she is authorized to operate. For those operating instrument flight rules (IFR) helicopters, to maintain instrument currency there is a six-month instrument competency training and check ride in addition to an annual training and testing requirement.

Being truly proficient in addition to being current is ultimately the pilot’s responsibility.

These training cycles serve as great refreshers, but you will likely fly several hundred patients in between those annual or semi-annual sessions, and the information learned has a tendency to erode over time. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations state that in order to carry passengers (crew/patient), the pilot has to have accomplished three take-offs and landings within the preceding 90 days, and for operations at night (one hour after sunset, up to one hour prior to sunrise) the pilot must complete three take-offs and landings during those hours. Training and exhibiting proficiency once or twice a year is a great starting point. Being truly proficient in addition to being current is ultimately the pilot’s responsibility. Decide to be the master of whatever airframe you’re piloting. Review aircraft systems, with a particular emphasis on emergency procedures; seek out answers to any questions that arise; and demand of yourself a mastery of knowledge so that when things go wrong, you have the confidence and knowledge of what’s happening and how to react. You owe it to your crew, your patient and yourself.

Falling back on our Three Little Pigs starting point, don’t be like the first two pigs: don’t take shortcuts. Do the work, do it right and never stop reinforcing it. The time spent in preparation, and the quality of the attention and effort you put into it, says as much about you as a person and as a pilot.

In the world of air medical helicopters there is an abundance of downtime. That time between flights where you are standing by, use that time, and use it well.

May 2022

Issue

In this issue:

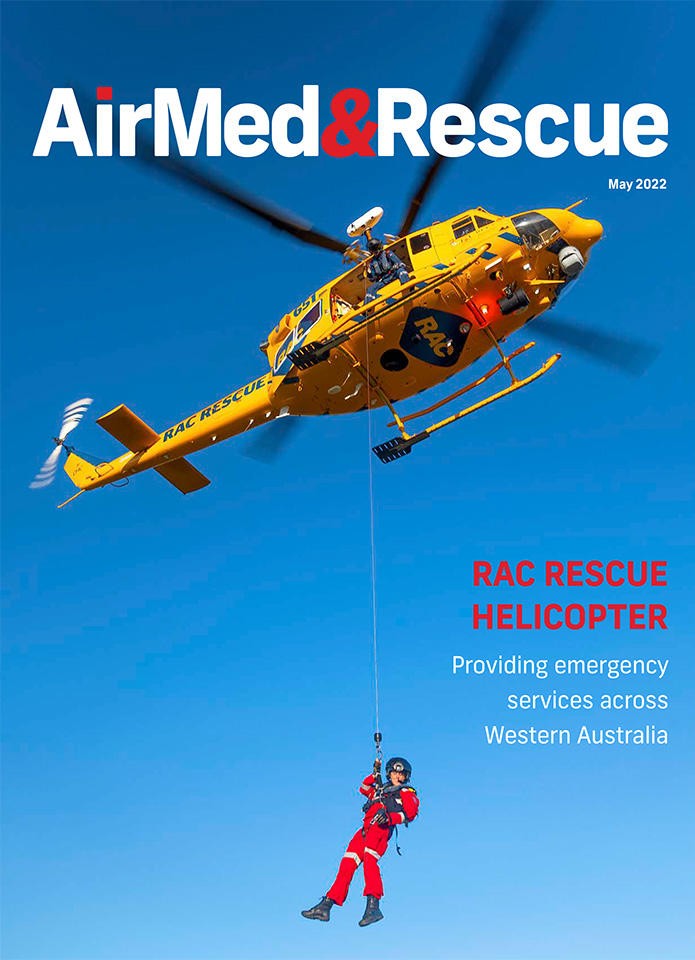

Dynamic hoisting; wireless communication solutions enhancing crew coordination; we say au revoir to the RCAF CC-115; introducing pre-hospital ECMO - nationwide coverage in the Netherlands; CAMTS' Executive Director Eileen Frazer looks at what critical care means; HEMS pilot Mike Biasatti explains how hard work and dedication pay off; and Dr Julian Wijesuriya on Airway Management interactive online learning course.

Mike Biasatti

A helicopter air ambulance (HAA) pilot in the US for 20 years and a certificated helicopter pilot since 1989, Mike Biasatti continues to enjoy all things helicopter. In 2008, the deadliest year on record in the US HAA industry, he founded EMS Flight Crew, an online resource for air medical crews to share experiences and learn from one another with the goal of promoting safety in the air medical industry. He continues to write on the subject of aviation safety, particularly in the helicopter medical transport platform with emphasis on crew resource management and communication.