RPAS – certification of aircraft and licensing of pilots

The pace of development in the remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) sector is bringing a host of opportunities for users around the world, whether for search and rescue, airborne law enforcement, aerial firefighting or surveillance purposes. However, with these bounds forward in capabilities from drone makers come headaches for regulators, who have to balance keeping up with demands from users for more freedom to take advantage of the capabilities of the equipment with that aviation gold-plated standard – safety

In the UK, this is particularly pertinent – it has one of the world’s most crowded airspaces in the world, with commercial airlines sharing space with private pilots in aircraft of all shapes and sizes – from World War II-era fighter jets to skydivers. Successful integration of RPAS flying within line of sight of the pilot has already been achieved; but when it comes to beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS), there is a lot of work yet to be done.

The employment of larger drone systems (from a regulatory perspective) is in a state of flux, as no regulation has been agreed and requires each large drone platform to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. It is up to the operator to demonstrate it is safe by design (platform), safe to engineer (airworthiness) and can be operated safely (operators).

Nigel Breyley, Director of Cyclops Air, spoke to AirMed&Rescue about the rise in popularity of drones, and the challenge it has brought with it: “Twenty years ago, most, if not all drone activity in the UK was either radio control model flying, or was done for and by the Ministry of

Twenty years ago, most, if not all drone activity in the UK was either radio control model flying, or was done for and by the Ministry of Defence

Defence. This included systems such as unmanned aerial targets for missile firings followed by the evaluation of the ScanEagle for maritime surveillance purposes and design and flight of the Observer RPAS. These activities took place in Danger Areas and segregated airspace and fell under military regulation.” Since then, however, the development of DJI-inspired drones for use by hobbyists has led to an explosion in drone sales, and unfortunately, believes Breyley, regulation hasn’t always been able to keep pace with the usage level and technologies involved. “The UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) seemed initially to be taken by surprise by the popularity of drones,” he told AirMed&Rescue, “and that the same technology being used on small DJI drones (used by individuals for fun) could be applied to larger drones that would be used for commercial purposes such as survey work and building inspections, by organisations outside the mainstream aviation community. The CAA, as many aviation regulatory authorities, was slow to recognise the growth potential of the industry, which has resulted in cases of the industry running ahead of regulation. This has led to poor practices by some operators and a patchwork of rules, some of which may not be fit for purpose.”

© Bristow

Concerns about lack of clear oversight

Modini works with Bristow to operate the Schiebel drone around the UK’s coastline in support of SAR service provision. James Earl of Modini spoke to AirMed&Rescue about how he believes the unmanned aircraft industry is being held back by a lack of clear regulatory guidance: “The primary issue holding back innovation and adoption of drones in UK airspace is a lack of clear and definitive regulatory oversight by the CAA. Current certifications for manned aircraft are based on weight limits and complexity – drones are categorized by weight and operational risk. The threshold to take a platform from the open category into the specific category is too low and the lack of detail in the certified category section mean that the specific category contains everything from perceived high-risk missions using sub 25kg platforms and 200kg highly complex platforms.”

The primary issue holding back innovation and adoption of drones in UK airspace is a lack of clear and definitive regulatory oversight by the CAA

Breyley said: “The rules for flying smaller drones within a pilot’s line of sight are reasonably clear and straightforward – so for the typical hobbyist user, using a drone isn’t an issue. The problem comes when a user wants to take the drone BVLOS. In the UK, there isn’t a recognised licence for pilots who wish to fly BVLOS: applications are assessed on a case-by-case basis and not always consistently. There has been discussion and work on a remote pilot’s license, but regulatory bodies including EASA and ICAO have been slow to develop one and the default to practices in existing aviation is not always appropriate. I have spoken with regulators who are hesitant to act without it being mandated by governments, despite the issue being one of flight safety, and have instead preferred to rely on the courses offered by manufacturers.”

Quality of products

The quality of manufacturing standards of RPAS is, at the moment, a bit of a mystery – there is no quality standard to which manufacturers of RPAS are held.

Earl said: “Manufacturing standards in crewed aviation are highly scrutinized and monitored – it has to be for safety reasons, but this is not the case when it comes to uncrewed aviation, there are no guidelines for the build quality, redundancy requirements or quality of materials or suppliers used in the supply chain. The CAA is not currently equipped to assess whether or not an RPAS is 100 per cent safe because the standards to which an RPAS should be built do not exist furthermore the CAA currently only does a paper check of RPAS and its safety features in the form of an OSC, they do not have the capability to check manufacturing facilities or the standard of component integration within an RPAS.

AirMed&Rescue spoke at length to the CAA about concerns raised by other commentators in this article, one of which is the certification of the drones themselves. Ed Purnell, who straddles the CAA’s policy and innovation teams, and JJ Nicholson, Assistant Director and Head of Campaigns for the Communications Department, were keen to share their experience and views.

“Regulations are always being updated, and we regularly consult with industry partners and take their feedback into account,” said JJ. “One we changed just recently concerned the introduction of a certification standard for drones – a set of marks for drones based on size and weight and that would determine what the person could do with that drone. It was due to come into effect next January, but manufacturers haven’t made any drones with the class markers on, and there is no body set up to oversee the class marking.” The CAA suggested postponing the proposal for two years, but the industry came back following a consultation period and said they were worried about ewaste – ie old drones not classified having to be simply thrown away. “So, we have now declined to set a defined date for this, instead looking at the longer-term use of drones already in existence, and where they can, they are going to give drones a longer life span,” said JJ.

Earl has concerns about the desire to develop a UK-specific standard: “The problem with developing any UK specific standard is that it would isolate the UK from the rest of the world creating fleet within fleet issues, which is likely to deter RPAS manufacturers from wanting to build compliant platforms for such a small market. It’s a difficult balance – to encourage innovation one should have a certain amount of freedom, but within a regulatory framework that encourages adherence to a transparent quality standard for the safety of the public and longevity of the industry.”

The CAA doesn’t believe such a standard would be off putting for a manufacturer. In fact, perhaps the opposite is true, said Purnell: “From a manufacturer’s perspective, it would probably increase usage of the product. It makes sense, and they could potentially charge more for their tech with a pre-approved product. It will drive the behavior and enhance the value of the product.”

© Roksenhorn - Wikipedia

BVLOS rules

Purnell pointed out that RPAS use in SAR is already commonplace, but restricted to VLOS – ‘they have to be able to see and avoid’, he clarified. JJ added: “BVLOS is a key global direction, but it has to be done safely. We have set out a roadmap for how BVLOS flight could happen, but it’s not about just making the drone and the drone world safe and capable, it’s a much wider aviation problem: equitable use of airspace. It’s about, within reason, everyone having fair access to the airspace.”

The CAA certainly seems keen to innovate – but more people, capacity and money needs to go into innovation to maximise the potential of BVLOS RPAS flights. The good news for the airborne special missions sector in the UK is that according to the organisation, ‘HEMS, SAR and emergency services will be the first to have a go’. “Trials are happening, but they are for now in a closed/restricted environment or in collab with other local airspace users,” added JJ.

The Brexit effect?

Prior to January 2021, the UK CAA came under the guidance of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Now, however, they are their own bosses. Much of the current regulatory material though, has come directly from EASA and has just moved into UK law.

Earl expressed concern that the UK could be left behind other countries’ ability to embrace the potential of RPAS due to being outside of EASA’s guidance. The

CAA, however, said that Brexit has had no adverse effect on the development of drone regulations in UK airspace. “There are benefits to harmonization of rules, of course,” said JJ, “but the benefit of where we stand now is that we have the flexibility to diverge if we need to.” As an example, EASA has also put off the introduction of the standard/class mark for drones as well, but has put a two-year limit on it where the CAA has decided not to.

Pilot competency

A key issue for furthering the cause of safe RPAS use is the competency of the pilots holding the controls. Breyley told AirMed&Rescue: “The CAA tells people they should do the manufacturer training course. The reality is that very few manufacturers deliver courses at all, and for those that do, the standards are frequently well-below par for the aviation industry.

The reality is that very few manufacturers deliver courses at all, and for those that do, the standards are frequently well-below par for the aviation industry

Most of the courses are designed by professionals from the tech industry; they are not pilots, or experienced training course designers. Drone manufacturers often don’t have the necessary aviation experience: they are predominantly staffed by engineers. This means that many have no idea of the difference between altitude and height in operating terms or the confusion caused by introducing GPS heights based on take-off location when flying BVLOS. In short, they understand the technology, but not the operating environment.” The CAA may not really be in a position to say for sure whether or not something is 100 per cent safe, as there isn’t the data on engineering and manufacturing that they have in manned aviation and they do not have the capacity to audit everything that comes their way. A lack of major UAS manufacturers in the UK due is in part due to this lack of clarity and oversight.”

The CAA, conversely, says that it performs due diligence on the courses it recommends RPAS users undertake. All providers are overseen by a sector team and their performance is audited once a year in a process that sees both their documentation and their processes being closely scrutinised. “It’s similar to what a flight school would have to go through,” said Purnell, “and the syllabus is similar to that required of someone applying for their private pilot’s licence.”

Training organisations have to pay to become a CAA-approved provider, and the initial application process is ‘extremely rigorous’, said the CAA. The syllabus has to meet all the required standards and the examination process is lengthy. What the CAA fail to mention here is that this is only for VLOS (visual line of sight) and EVLOS (extended visual line of sight) training, there is no such training or audit team for BVLOS despite the CAA issuing Operating Safety Cases (OSCs) allowing BVLOS to happen in the UK.

There is still work to be done in this area, though, as Purnell pointed out: “We recognise that further competency training needs to be introduced particularly for BVLOS, so innovation and wider CAA teams are working together to put together what this could look like in the future. We need to build the future competency model. This would be delivered through the RAE network through consulting and gathering data on BVLOS trials.” He added that the CAA is working closely with EASA and FAA to watch what they are doing, but don’t expect any results soon on this one – with so many dependencies to take into account, no timeline was given.

Breyley said: “Regulators have understandably been waiting for technology to shoulder some of the burden of safety, such as through the development of detect and avoid sensors to enable BVLOS, but that should be accompanied by recognising that comprehensive training standards and well-trained knowledgeable people also enhance the safety of operations.”

September 2022

Issue

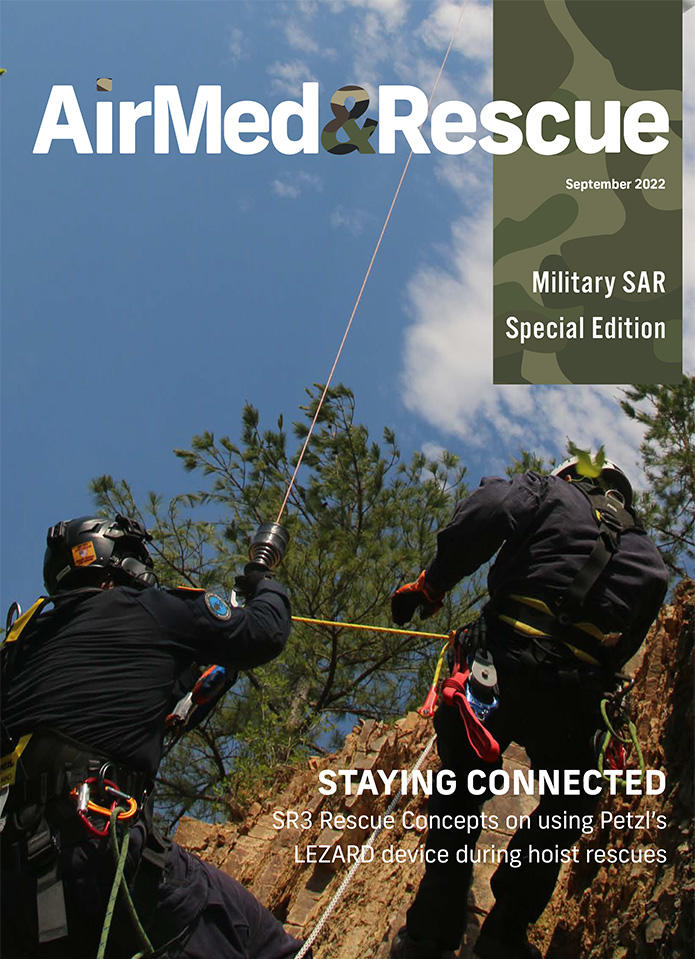

In our September Special Military edition, we consider challenges faced both on and off the battlefield, and how modernization is at the forefront in overcoming these. From the reality of search and rescue operations, aiding the care of injured servicemen and women, to how technology can transform battlefield medicine. We also talk to Leonardo about the capabilities of the AW149, and SR3 Rescue Concepts discuss the new innovation from Petzl designed to aid in mountain rescue.

Editorial Team

The AirMed&Rescue Editorial Team works on the website to ensure timely and relevant news is online every day. With extensive experience and in-depth knowledge of the air medical and air rescue industries, the team is ready to respond to breaking industry news and investigate topics of interest to our readers.