Overcoming obstacles for patient repatriation

Dr Ioannis Mamidakis, Medical Director of Athens-based Gamma Air Medical, describes a recent air ambulance repatriation of a critically ill patient from Libya to Greece that took place against the backdrop of the Libyan civil war

Sometimes it’s necessary to organize air ambulance flights where risks are taken that would not normally be accepted. Thorough and detailed planning, combined with the establishment of effective communication channels, can reduce risks to acceptable levels whereby a repatriation mission can effectively take place under challenging circumstances.

Libya’s devastating civil war

In recent years, instability has dominated Libya’s political climate and has caused dramatic consequences for the country’s population. Lack of political unity has meant that there is no formal legal framework to protect the rights of refugees, making them extremely vulnerable to human rights violations. The situation has been made worse by civil conflict, which has degraded the country’s infrastructure, affecting – among others – the health system and hospitals.

Case description

Against this challenging background, Gamma Air Medical received a request to follow up the case of a patient hospitalized in Misrata, a city in north-western Libya, situated on the Mediterranean coast 187km east of Tripoli and 825km west of Benghazi, near Cape Misrata. Gamma was also asked to assess if the case was considered ‘fit-to-fly’ for repatriation to Athens.

The company’s task began by making contact with the treating hospital in Misrata. It was a difficult jigsaw puzzle of piecemeal medical information, gathered on a daily basis, which was not at all easy to fit together, given the difficulty in communicating with the hospital’s administrative departments and the language barrier with the medical and nursing staff on the ward where the patient was under care.

The patient, a 63-year-old Greek sailor, was transferred in a serious condition to the Libyan Red Crescent Hospital in Misrata on 8 February, with generalized edema (anasarca), which had gradually developed during the month prior to hospitalization. Additionally, upon admission, he was dyspneic due to lung congestion, presented tachycardia (over 115 bpm) and profuse sweating. The medical history of the patient was detailed enough to consider the situation as serious: Diabetes Mellitus II insulin-dependent, pulmonary edema, obesity (160kg), ascites (free liquid in the abdominal cavity) and anemia.

Following admission, the patient was transferred to the HDU (High Dependency Unit) and treatment was started with diuretics, antibiotics and albumin IV infusion. An improvement was noted over the next two days, with the edema beginning to subside, but not the ascites, and the patient presented spontaneous diuresis.

On 12 February, the patient showed a sudden deterioration with hypotension (90/50mmHg), tachypnea (22bpm), a decrease in oxygen blood saturation (78 per cent with oxygen mask) and fast representation of the generalized edema. The patient went into acute pulmonary edema and was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where he was intubated under sedation with morphine. After intubation and stabilization, the patient presented 90 per cent oxygen saturation with 100 per cent oxygen administration; blood pressure was 110/60mmHg and the heart rate was stabilized at 95bpm; the diuresis was satisfactory, but supported with diuretic doses of dopamine.

The patient’s family asked about the possibility of him being repatriated to a hospital in Athens with advanced ICU facilities. For this reason and in view of his critical and ventilator-dependent status, it was essential that this patient transfer was undertaken using an ICU-configured air ambulance aircraft.

The patient’s relatives had started to make arrangements for this before contacting our company, and they had already spoken with two other air ambulance providers about undertaking the repatriation mission. However, both of these providers said they could not operate in Libya due to the high risks involved because of the security situation.

Obstacles

Due to the communication difficulties already described with the treating doctors at the referring hospital in Misrata, there was also no chance of the Gamma Air Medical team assessing the patient in situ at the hospital. Another consideration, therefore, was arranging and securing safe ground transportation of the patient from the hospital to Misrata airport.

These problems were solved by maintaining daily contact with the hospital’s medical personnel, from the point when we were asked to take on the case until the time when the flight was actually made. It was arranged that the patient would be transported to Misrata airport by a ground ambulance from the hospital, escorted by the hospital’s specialist medical team.

As Libya was considered a war zone, we had to contact the Libyan aviation authorities to request a landing permit at Misrata airport – not an easy task, made worse by complicated and excessive bureaucracy.

“The patient’s condition was

a concern to us as he was

intubated but awake. He was alert,

restless and trying to remove the

endotracheal tube with his hands”

Through our ground handler at the airport, we also got in contact with the immigration authorities to head off any problems when the patient arrived for his repatriation flight and to ensure his departure for Greece was not held up. We also had to contact the Italian aviation authorities as we needed to obtain overflight permission from Italy (at that time, no flights originating from Libya were permitted to transit Italian airspace). Intensive negotiations, accompanied by an extensive list of supporting documents, meant we were able to overcome these obstacles and achieve all our goals.

Execution of the flight

Execution of the flight Following all the protocols already described and observing the specific regulations for this particular mission, detailed medical and flight plans were made to cover all eventualities– predictable as well as unforeseen – with the objectives of a safe and uncomplicated evacuation. A Learjet 35 air ambulance with Gamma’s medical team onboard (two doctors, one of whom is the author of this article) departed Athens for Misrata on 14 February, where we arrived after a two-and-a-half-hour flight.

Our medical equipment, in addition to our aircraft’s stretcher and the almost unlimited onboard medical oxygen supply, consisted of a Hamilton T1 ventilator, ProPaq Encore cardiac monitor, Physio Control 10 defi brillator, OB 1000 suction unit, Fresenius Cabi electric pumps, medical oxygen cylinders (aviation type), consumables and medicines.

Upon arrival at Misrata airport, we received the patient on the tarmac, where he arrived by road ambulance escorted by a doctor and a paramedic. The patient’s condition was a concern to us as he was intubated but awake. He was alert, restless and trying to remove the endotracheal tube with his hands. He was trying to talk, but obviously he couldn’t as he had the endotracheal tube in his mouth. The medical team that had escorted the patient explained they had run out of sedatives on the way to the airport. Gamma’s medical team stabilized and sedate the patient before transferring him from the ground ambulance to the aircraft.

He was connected to electric IV pumps to receive adequate doses of sedation with Propofol and Dormicum (Midazolam), as well as to the Hamilton T1 ventilator with our portable oxygen cylinder, to provide him with enough medical oxygen. The patient was sedated on Propofol 1 per cent 10mg/ml with 35ml/hour, and Midazolam 150mg in 100ml N/S 0.9 per cent with 25ml/hour, remaining intubated and mechanically ventilated with the following parameters: SIMV mode, Tidal volume 600ml, FiO2 0.7, respiratory rate 14/ min, PEEP 7cmH2O.

Our cardiac monitor was used to keep his hemodynamic and saturation profile under control, and once all the above were in place, the patient was moved out of the road ambulance. He was transferred into the aircraft using special ramps to facilitate the loading of such a heavy patient, and then positioning him on the aircraft’s stretcher.

The patient’s vital data prior to departure were: BP 140/80mmHg; heart rate 80bpm; SPO2 92 per cent on FiO2 70 per cent; temperature 37.2°C. During the flight back to Greece, we had to make some adjustments and changes to the ventilator settings, as well as to the doses of the sedatives being used (taking into account the patient’s liver status) to improve his respiratory performance and hemodynamic status: Propofol 1 per cent 10mg/ml with 25ml/h; Stedon (Diazepam) 10mg IV 30 minutes before landing in Athens; CPAP mode, 50 per cent mixture, SatO2 95 per cent, respiratory rate 17/min; blood pressure 110/80 mmHg; heart rate 90bpm.

Among all the arrangements that Gamma Air Medical had made, the last one was for a road ambulance with ICU confi guration to greet the air ambulance at the airport. On touchdown in Athens, the patient was transferred with the ICU advanced cardiac life support ground ambulance to the admitting hospital in the Greek capital.

Epilogue

In this particular case, the problems we had to deal with were many and various. We faced difficulties clearing our overflight through the Italian Flight Information Region (FIR) and then securing landing permissions in Libya. The rules concerning both matters were very strict and we had to satisfy the requirements of the relevant aviation authorities, planning our flight in such a way so as not to violate specific airspace overflight rules. We managed to avoid excessive delays regarding the assurance issues, due to our destination (Libya) being declared a war zone.

It was complicated getting in contact with the referring hospital to collect medical information on the patient’s status and assess his medical condition, elements that were very important to us as we had to select our medical crew and equipment accordingly. At the same time, we were given the wrong patient’s name and we had to make various cross-checks in order to complete the necessary immigration procedures.

The difficulties we faced communicating with the treating doctors at the referring hospital; the complexity of cross-checking the patient’s medical history; the need to take prompt action due to the urgency of the referral; the difficulty in obtaining overflight and landing permissions; and the severity of the medical case.

Cases like this are often found in our geographical area and are not uncommon because of ‘war zone’ situations in the countries that surround us.

May 2022

Issue

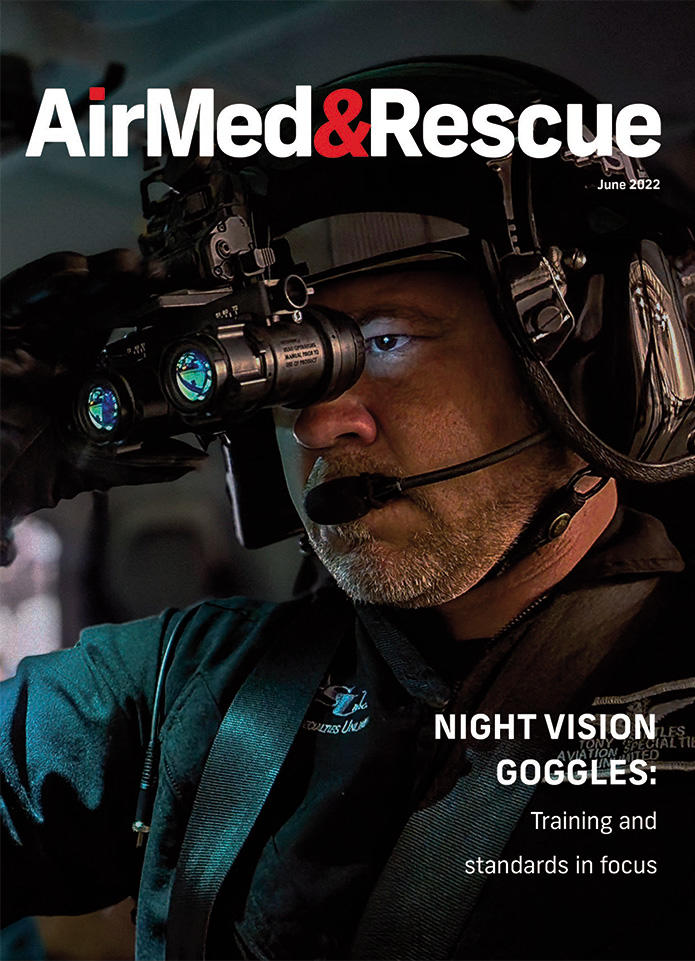

June’s edition of AirMed&Rescue considers sustainability across the industry, communication and asset management tactics during large-scale events, along with night vision goggle training standards.

Dr Ioannis Mamidakis

Dr Ioannis Mamidakis, Medical Director and Flight Team Head Doctor of Gamma Air Medical, has been committed to aeromedical transport for over eight years. His specialties include intensive care, cardiac surgery intensive care, and Thoracic surgery.