Overcoming obsolescence

Peter ‘Foo’ Kennard explores fighting obsolescence in aviation and how manufacturers are tackling this ongoing battle

There are few phrases in civil aviation as frustrating as 'Aircraft on Ground' (AOG). In the commercial sector it means that an expensive asset is sat idle not earning revenue, and potentially incurring parking fees whilst clicking down time to its next calendar servicing requirements. In the aviation business, time equals money. In Aero Medical, SAR and other Emergency Services provision, an AOG platform, aside from the financial impacts, can make the difference between life and death for those that need its life-saving presence.

In Aeromedical, SAR and other Emergency Services provision, an AOG platform, aside from the financial impacts, can make the difference between life and death for those that need its life-saving presence

Platforms can end up AOG for a number of reasons. Sometimes it can be kinks in the logistic support system; a 'just in time' service that delivers key spares 'just too late'. However, as aircraft and their systems age, another factor starts to increasingly come into play, obsolescence.

Obsolescence can impact an aircraft's operation in several ways. Firstly, and most obviously, mechanical and rotable spares for the aircraft itself can become increasingly difficult to source, and therefore become more expensive, as the platform ages. Most major mechanical components, such as engines, blades, and transmissions, are normally straightforward (if expensive) to overhaul, especially if for a popular platform that's been produced in large numbers over an extended production run. In some cases, the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) will continue to provide an element of spares support long after the last whole airframe has been produced, whilst in others, third parties will step in and take over - especially for niche small volume spares.

In some cases, however, the only way to maintain a supply of spares is a little more drastic.

The MD900/902 Explorer series was a platform widely employed by police and HEMS units in the early days of UK aviation support. It remains a capable and compact machine, ideal for HEMS work in tight landing sites and with the added benefit of the 'No Tail Rotor' (NOTAR) system in lieu of a conventional tail rotor, increasing the safety of the aircraft by reducing the impact of the pilot drifting the tail into an obstruction, and protecting those operating around it as there's no danger of an individual inadvertently walking into the tail rotor. I evaluated the MD902 for a client and thought it was a far sweeter machine to fly than its natural competitor, the EC135. Once you got used to the slightly eccentric cyclic/collective arrangement, and the slight lack of crispness in yaw control in the hover (likely because of the NOTAR system), I marvelled at the great visibility, how powerful it seemed to be in the climb and swiftly adapted to the intuitive cockpit ergonomics. It looked like a great platform for the role it was being purchased for. However, prior to flying the machine, a quick internet search revealed multiple tales of woe regarding Explorers spending extended time AOG awaiting spares. Although, technically, the MD902 line was still 'open' at the OEM if customers ordered new aircraft, the reality was that spares support for a few crucial components was lacking and the supply had effectively dried up. The vendor acknowledged this, then showed me their proposed solution. In a hangar next to the flight shed was a stock of 'N-Reg' Explorers being stripped for spares.

They acknowledged that their obsolescence management plan for continuing to support the aircraft in the UK was to scour the globe for Explorer airframes for sale, snap them up, ship them to the UK and spares recover them, carefully tagging and shelving each component as it was removed so that the 'golden thread' of airworthiness oversight could be maintained. Though tempted, I walked away and bought an EC-135 instead; despite being second best for the role, the assurance from the OEM, Airbus, and an extended diaspora of third party maintenance shops and spares providers gave me the confidence that, as a single-aircraft operation, potential AOG times could be contained. I wanted to ask the newly re-financed, and under new management, MD Helicopters for an update on MD900/902 support, but unfortunately no response was forthcoming before publication. I truly hope that such a fine machine can overcome this reputational inertia, as it still has many excellent characteristics for EMS and police aviation operators. Whilst a representative from MD Helicopters was unavailable for comment, perhaps actions speak louder than words. Under the new management, the first new-build MD902 helicopter for several years has been constructed - seemingly as a company demonstrator to compete for future sales. Industry sources have also reported that the ’new’ MD Helicopters are investing in their support and spares holding. Perhaps MD Helicopters has decided that only it can ‘buy out’ the obsolescence concerns of its largest and most capable machine, and in doing so return customer confidence in what remains a superb all-round machine for EMS and police applications.

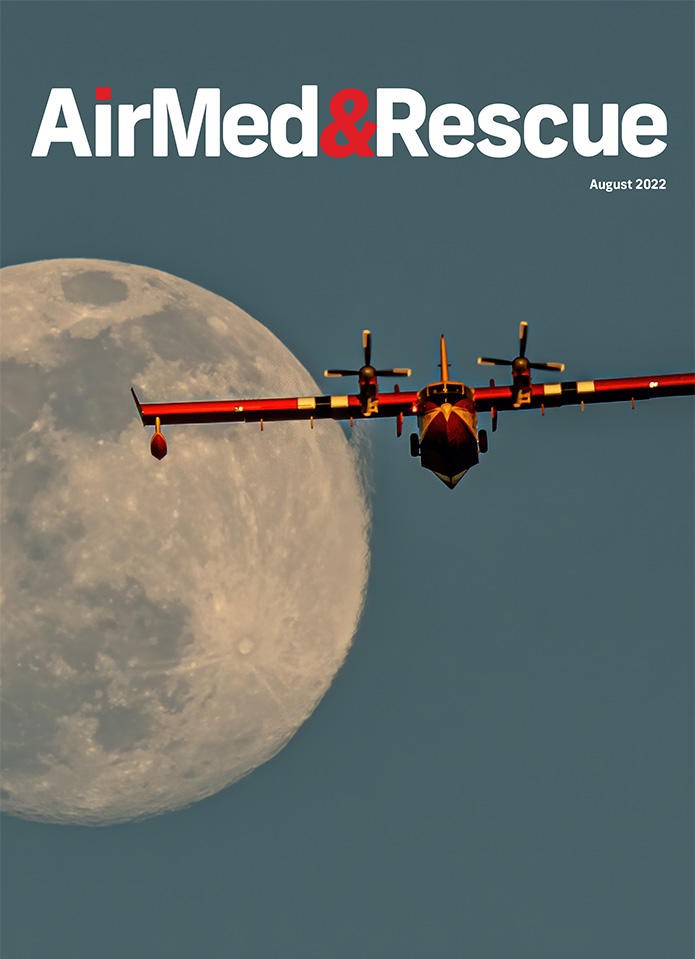

Such whole airframe obsolescence concerns are not restricted to the helicopter market. In the US, the Air Attack industry has long waged its seasonal campaign against forest fires using aircraft that, by contemporary commercial and military standards, are deep into their flying careers. Shannon De Wit, of Conair Group, a specialist aerial firefighting organization with currently 70 aircraft currently 'on the books', was most generous in espousing Conair's views on the subject. Conair take a holistic view, and as Shannon puts it, Conair manages obsolescence by, 'using 50 years of experience and inhouse expertise, Conair manages the operational risks of aging aircraft using data to forecast and schedule heavy maintenance. Long-term partnerships with customers who commit to multi-year contracts has enabled Conair to move into the future, retiring older aircraft before costs and obsolescence incapacitate fleets.'

Conair acknowledge that this decision point to 'off ramp' older aircraft in favor of newer, more supportable, aircraft is always difficult. Justin Sellars, Director Supply Chain and Facilities notes that, 'obsolescence is a major issue for Conair and we see it more frequently in our aging legacy fleets. In some cases, specific subcomponents required for a repair may no longer be supported and an approved alternate solution can take time to come online. We safeguard against part supply issues by carrying more inventory on-hand than would otherwise be required.'

This is a sensible approach.

In the UK military, when I was helping to support critical avionic subsystems on the RAF's CH-47 Chinook fleet, such as Defensive Aids Suites, radios, and navigation equipment, we'd often take a similar view. We'd title it a 'lifetime buy'. The figure would be arrived at by considering the fleet size now, and into the future, the anticipated utilization rate, the published Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) and either the planned Out of Service Date (OSD) for the aircraft or when the next Mid Life Upgrade was due, where the component would be replaced by a new capability. This would give us a number to purchase, which we'd normally add a small margin of five to10 per cent to, and, with luck and careful husbandry, this one-off purchase would be sufficient. Of course, there are drawbacks to this approach. Firstly, anticipated utilization rates and OSDs might be rendered inaccurate by events. Moreover, stock sitting on a shelf may well have a finite 'shelf life' and any warranty offered will inevitably expire as time passes. There is only so long a 'lifetime buy' can last.

This is just the approach that NASA has taken when purchasing chip sets for its new Orion spacecraft. The selected chipset comes from a 2003 Apple iBook G3, and it was picked because it's compatible with the Orion's early 2000s designed architecture and it's a robust, well proven, technology. NASA just had to find and buy up hundreds of 2003 iBooks to put enough chipsets onto the shelf. It is somewhat amusing to think that an intern at NASA was probably spending a summer placement buying old computers on EBay.

However, back to that comment about when to 'take the off ramp', Justin Sellars, Director Supply Chain and Facilities at Conair agrees as eventually, 'entire systems will no longer be supported which can create complicated issues for operators as there may be existential questions raised on being able to continue using the aircraft.'

Conair faced such an issue in the 1980s with their fleet of ex-military S-2 Trackers. The World War Two era engines (the same as used on the B-17 bomber) were becoming expensive to maintain, and the growing warbird movement provided an unwelcome competitor for the remaining spares. The airframe itself remained a useful asset, so Conair took the courageous step to zero-time the airframes and re-engine their fleet of S-2s with the near ubiquitous P&W Canada PT-6A turboprop, used by hundreds of commuter and military training aircraft such as the King Air/C-12 family and the PC-9/12/21 trainers. Instantly, the useful life of the S-2 has been extended, and obsolescence concerns kicked down the road.

Even with such ambitious projects as re-engining the S-2, eventually there comes a point where that 'existential question' is raised. That's the time to change horses. As Conair's Jay Berry notes, 'the risk of whole aircraft obsolescence is why Conair is taking the proactive step to replace our legacy fleet of Electra L-188 and Conair CV580 airtankers with new, modern Dash 8-400 airtankers.' The plan is that the Dash 8 will have replaced the legacy types by the end of 2022, easing any concerns about remaining structural life and parts obsolescence, as well as providing a welcome uplift in both capability and availability. Newer aircraft mean fewer days AOG.

There are more subtle approaches to obsolescence, and operators don't need to risk miscalculating on a lifetime buy nor radically modifying their existing stock to 'buy out' the risk.

There are more subtle approaches to obsolescence, and operators don't need to risk miscalculating on a lifetime buy nor radically modifying their existing stock to 'buy out' the risk

Increasingly, modern technology can take the strain. I spoke to the crews at the London Air Ambulance Service (LAAS) about how they were eking out the useful life of their MD902s until a replacement could be found. One such problem was an increasingly unsupportable, and out of date, installed avionics/moving map system. Any pilot that's flown helicopters around London can attest to just how important accurate navigation is. The cost of replacing the obsolete navigation system with newer, certified, equipment was excessive – especially as the MD902 was nearing the end of its service. However, some lateral thinking came into play. Car drivers rarely pay the exorbitant OEM costs for upgraded SatNav software for their vehicles. Instead, they use a constantly updated map/nav system on a smart phone or tablet. This fact has increasingly been acknowledged by car manufacturers, who now offer Apple Car Play and Android Auto as an option, enabling drivers to use Google Maps or a bespoke navigation system, such as 'Waze' to provide reliable navigation and traffic data. LAAS took the same approach and purchased the Airbox ACANS (Aviation Command & Navigation System) software, installed upon an Apple iPad. For LAAS, the beauty of ACANS was that it required no expensive installation on the aircraft, little to no 'down time' and as the iPads are charged and updated every night, they are always flying on the latest map and navigation information. Add in the ability to interface with other Emergency Service air and ground units, it's clear that the obsolescence management approach adopted by LAAS has also provided genuine capability upgrades and of course, it is fully portable to their next aircraft, minimising costs and crew re-training.

The ultimate way to avoid obsolesce in the first place is to contract out the risk. 'Contracting for Availability' places the onus on obsolescence management, and the risk of an AOG event, firmly into the hands of the organization(s) that the operator leases the aircraft from. Of course, the operator pays for offloading this risk, and it is factored into whatever standing charge and hourly flying rate they agree to pay. For smaller organizations, avoiding the management overhead of such issues can be a genuine boost to productivity, and a 'turnkey' approach is far easier to predict in terms of cash-flow.

Fighting obsolescence in aviation is an ongoing battle, especially for those second and third owner organizations taking on used platforms partway through their working lives. A robust requirements plan, a solid cost model, and realistic assumptions can all help to create a blueprint that keeps expensive aircraft in the air for longer, saving both money and ultimately, lives.

August 2022

Issue

In our August issue of AirMed&Rescue we look at survival, sustainability, and performance; both in the air and on the ground.

Paul 'Foo' Kennard

Paul 'Foo' Kennard is an Independent Aerospace & Defence Professional, and former RAF chinook pilot