Interview: Stu Sprung, Chief of Flight Operations, Aviation Management Unit, CAL FIRE

Fighting fire in California: Jon Adams spoke with Stu Sprung about the CAL FIRE approach to tackling fires with one of the world’s largest dedicated aerial firefighting fleets

Why did you become a firefighter?

A family member was Assistant Chief at San Francisco Bay Fire Department, so I was exposed to it from an early age and thought it was pretty cool. I was actually in college at University of California, San Diego, studying to go to medical school and ended up at Delmar Fire Department, right near the campus. That influenced me enough to become a paramedic instead. Similarly, what made me want to become a pilot was also family. My grandfather, Jack Pickup, was a famous pilot in Canada, known as the Flying Doctor in the 1940s and 1950s. He was the only doctor in the northern Vancouver Island and had to cover 10,000 square miles. There were loggers, fishermen and miners, so they often got traumatic injuries, but it would take too long to get to them. So, he learned how to fly and bought a seaplane. He could get the patients and bring them back to the hospital. He always made me proud – so being able to continue that legacy is a big deal for me and my family.

Chief of Flight Operations at the Air Management Unit is a position of responsibility. How do you approach a multitude of demands?

I focus strictly on operations, so mostly anything that happens post-release from maintenance and in the field. We have 130 or so fixed- and rotor-wing pilots that fly about 60 aircraft. Out of our 23 air attack and Helitack bases, 13 are air attack, eight Helitack, and two joint. These aircraft cover the state responsibility area, about 31 million acres out of the state’s 104 million acres; 84-85 million of which is classified as wildland. We work closely with federal and local counterparts with 150 local government cooperators, serving 40 million Californians, plus visitors. In addition, we have about 50 or so other pilots because we depend on 24 additional contract aircraft, for a dedicated state-owned fleet – 60 aircraft still hasn’t been enough in recent years. Altogether, this makes up one of the world’s largest dedicated aerial firefighting fleets.

We commit a lot of time to training: one-third of our entire year is getting our pilots and crews spooled back up for the season. Another source of pride is a 98 per cent maintenance in-service rate, which is tremendous. Before I came here, I worked for the airlines, and I don’t think we came close to that. But for us, because we’re so mission-centric and respond within minutes of the alarm, we need that reliability.

I’m also dealing with one-off stuff; unique things that happen with such a large organization. There’s also a lot of planning, and I try to build in redundancy to account for the unexpected. It’s important to leave some bandwidth to account for these events. Making sure I stay ahead of the game means I don’t get overwhelmed, especially when there’s a lot of fires going on.

How have things changed over the years?

We are constantly re-evaluating our program to meet our new normal. In 2020, the state burned four million acres, which was double the previous record. In 2021, it was two million acres, which would have been our biggest year ever, barring 2020. Last year, we had a decrease that allowed us to really fortify our program with our exclusive use aircraft, increasing our in-service response aircraft by 50 per cent. In 2022, we actually had eight per cent more fires than the year before, but only 14 per cent of the acreage was burned. A lot of that was because we didn’t have the major weather events that gets these big fires going – but we had also put a lot more metal and aircraft out on initial attack.

We’ve transitioned from our trusty single engine, the Bell Huey, to Sikorsky S70i Fire Hawks. This nearly triples our water-dropping capacity from 340 to 1,000 gallons. We have a bit of reduced capacity because of tools and weight, since we also use them as rescue aircraft. The Hawks not only give us more performance, but provide an airframe that allows us to venture into night firefighting – a priority for us. We have a large and remotely spread-out area, over 31 million acres. We don’t know where the next fire will be, so we can’t plan for it, and there isn’t a lot of ambient lighting. Five of the 10 Helitack bases will be night-firefighting capable – two are already in service, in Hemet and Vina.

We also have the C130 large airtanker program to address the increase in fires. Our current Grumman Aerospace S-2t airtankers carry about 1,000 gallons of retardant, while these new C130s will carry 4,000 gallons. We don’t have a lot of spare aircraft, so the C130s allow us to pull some aircraft and put them into heavy depot to extend the life of the entire fleet.

We’re also adding to our fleet exclusive-use Type 1 helitankers. There’s only about 20 or so interagency carded Type 1 helitankers in the world – meaning that the US Forest Service creates the standards and then certifies those for safety; the gold standard for certification of such an aircraft. We have 12, and they carry almost as much as a large airtanker, about 2,600 gallons. It not only fights fire with water, but can also build a line with retardant. It’s a really versatile tool, and I think more companies will invest in them.

Will you still have to expand the fleet further, and are you looking at other technologies to manage the expected increase in wildfires?

Emerging tech, such as incident awareness and assessment aircraft, is being incorporated into our fleet. For ground incident commanders and incident management teams, it allows them to see and map the fire the day before, and then map it again. They can reach out to know which area has done nothing, and which has exceeded where it was the previous night. We can estimate pertinent negatives, such as where it is cold, so they can redeploy resources as needed to the areas that have moved outside the previous line and get ahead of it.

Drones are coming quick and fast. They have been an enormous help; not just for mapping, but infrared in real time. A ground crew can put a drone in the air and see if a perimeter has been hopped over by embers. When there’s no aircraft available, it presents the ability to do mapping and take advantage of that kind of quiet time to get ahead on the intel.

One key area for drones is torch operations for backfiring on existing fires, to get ahead of them when winds are low and temperatures are cool at night. Flying a helicopter and dropping fire from it – over a fire – is really dangerous, so a drone completely mitigates the life-threat to the crews. They’re also practical for vegetation management in the off-season at high-threat areas, to protect against potential fires.

Another improvement is the increased speed at which information is obtained. It’s a factor for our operations to react quickly and transition into effective mobilization.

Wildfires are often seasonal, so what does crew training look like in the quieter moments, and is there rotation between vehicles/craft?

Our training is threefold. For new pilots, we do our initial training for all aircraft – then it’s just recurrent. We have about a week on the ground, then everybody comes in for a week or so of recurrent training with the same basic template of missions. If there’s high-risk issues we noticed in the previous year, we’ll emphasize that specifically.

Training also incorporates Air Tactical Group Supervisor Training or military airborne firefighting systems. We also use other agencies because we don’t just work alone – it’s more realistic to how we experience the actual incidents.

Although I fly the Huey, the OV-10 and the C130, our pilots generally work with just one aircraft tactically. This is a significant mitigator to such things as negative habit transfer. Saying that, we do have one base where the tanker pilots fly the OV-10, but they have experience in the aircraft already and, because it’s such a remote base, it’s easier for staffing to keep all the crew there, versus having to bring people in and out to cover them.

It’s a priority for our program to keep our fleet with as few aircraft models as possible. All our models are built almost identically, so you can hop into any single type and they all operate very similarly.

What special equipment is actually required for wildfires?

All new aircraft are tanked, because there are Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules about flying over congested areas with an external load, such as buckets. There’s wildland and people are living right in the middle of it, so we often have to fly over houses and congested areas to get where we need. Having tanks mitigates flying restrictions, really giving us versatility.

We also want helicopters to be night vision goggle (NVG) capable. It’s our intention to use all these aircraft for night firefighting, somewhat new to CAL FIRE. Many pilots, especially those we’re bringing on now, are previous Black Hawk pilots with extensive NVG experience – a number were helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS) pilots who did NVG operations. Only a few will start training from scratch.

They aren’t ‘equipment’, but the special resource we have are the nine firefighters in the back of the Hawk. There are two captains, a crew chief, then the rest are firefighters. Those are the real resource that put out the fires. I’d like to emphasize that all the air program does is buy time for the ground firefighters. A fire is not out until it’s all the way out, and we can’t do that from the air. We also work as insurance for them. If they get in a pickle, we sometimes have the ability to come right over and mitigate any threat in a very short period of time.

How are the different aircraft prepared for different types of fire, and is the equipment interchangeable?

We are an initial attack fleet, which means that when the fire alarm bell goes off, crews go straight to the fire. Our mandate is to respond to any blaze in the state responsibility area for the 31 million acres within 20 minutes, and to keep 95 per cent of them under 10 acres. That’s our prime directive, which ties into our 98 per cent in-service rate. If our aircraft are broken down, then they can’t get there, which is why we spend so much time on ensuring they’re available and the mechanics at the bases are supported. The Hawks all have mounted hoists for rescue operations as well, but essentially they’re used according to their primary design.

Our priority is always a new start and to keep that fire small. We have a lot of area coverage from the bases and our concentric response rings have a ton of overlap, which is why most of the helicopter bases are separate from fixed-wing bases, so we can always hit that 20-minute response deadline.

For extended attack fires, we bring in contract aircraft. The goal is to release our own aircraft back to base to be ready for a new fire that hasn’t started yet – that’s what makes our operations so successful, as we have our aircraft available when needed.

With a large fleet being put under immense strain, how do you manage maintenance and repair?

We work very closely with the original equipment managers (OEMs), such as Lockheed Martin on our emergency C130 program, and United Rotorcraft, who we contracted the Sikorsky Black Hawks through. We also use other agencies that operate the same aircraft. If there’s a question that we have, we will collaborate with Los Angeles County and San Diego City and the other operators of the Hawk.

We have 150 to 200 maintenance personnel that that are highly trained individuals. We also find a lot of people gravitate to our program from the military because they really connect with the tactical and mission environment – it’s not like just flying the airlines around, there’s a higher purpose. So we see a lot of personnel that have background in the aircraft that we have. Unique to our maintenance crew is that they react with the same urgency as our first responders. When an aircraft is out of service, they are on it. We have a Pilatus and a couple of Cessna 206s that they hop in at the base and get those aircraft back in service as soon as humanly possible. It’s impressive to see and they do such a phenomenal job – tying back into that 98 per cent in-service rate. Most of those engineers spend the rest of their career here – for the most part, this is a pinnacle program for them.

How do you organize and communicate with other operators that are attending the same emergency?

Airspace deconfliction is a huge priority for us. We have more aircraft in a confined area with our fires than any other mission environment, with the exception of military operations. We have what we call a Fire Traffic Area, which is essentially a Class Charlie Airspace concept. It has notification rings coming in, and predetermined altitudes and orbit rings to keep it simple for everybody and well publicized that way. We do a lot of outreach at the beginning of the season, especially with cooperators. HEMS operators, law enforcement and media all use the airspace, so we reach out to them, making sure they understand that they can see what the Fire Traffic Area looks like – and visualize what the aircraft are doing.

We also have a common frequency that we share. That is the back-up air-to-air frequency that all of our aircraft use, purely for safety. We communicate that frequency to the HEMS operators, law enforcement and the media. If they need to make contact with us, or we need to make contact with them, it’s ideal. An example would be if they need to clear the area for some reason.

Obviously when we set up temporary flight restrictions, we comply with the FAA regulations and have a tactical air officer who monitors that frequency as required. So, if someone needs to transition into the airspace – say a HEMS aircraft needs to get in when lives are at stake – we’ll make space. We realize that there’s a lot of mutual missions going on, so we work really hard to make sure that everyone gets done what they need in a safe way.

What are the next challenges?

CAL FIRE is a big agency, with almost 11,000 people. We are, I believe, the largest fire department in the country, nearly the largest in the world.

The program started in 1958 and has grown exponentially in the past five years. We have nearly doubled the personnel in just that period and, fortunately for us, Governor [Gavin] Newsom has been very supportive, seeing the value of what we do in the 20-minute response time. So, we’ve been able to get 10 S70i helicopters; and then another three, because we realized that to provide the adequate maintenance, we needed more spares than we had for the Hueys. We’re getting seven C130s from the Coast Guard, outfitted with tanks. Also, bringing on these 24 contract aircraft essentially increases our own state-owned aircraft by 50 per cent, meaning a lot of metal has come our way in the past five years that we didn’t have before.

The challenge is how we approach them. We have the aircraft, so now we must focus on sustainment. We need to keep them operating safely and effectively, allowing them to do what they’re designed for. It takes a lot of infrastructure, equipment, parts, personnel and administrative backing – all the behind-the-scenes paperwork, with people moving in different directions. We were able to increase our administrative support, which helps lift the whole program. That’s our focus: sustainment of current resources. Not just aircraft, but the people, in a high-stress environment.

A big concern for us is wellness of not only our air crews, but ground crews and firefighters. It’s become one of the number one killers of our people, so we need to put our money where our mouth is and get them the rest they need, back with their families. They often leave for months on these fires, so we want a work-life balance. I think that’s our big focus – looking towards our people.

March 2023

Issue

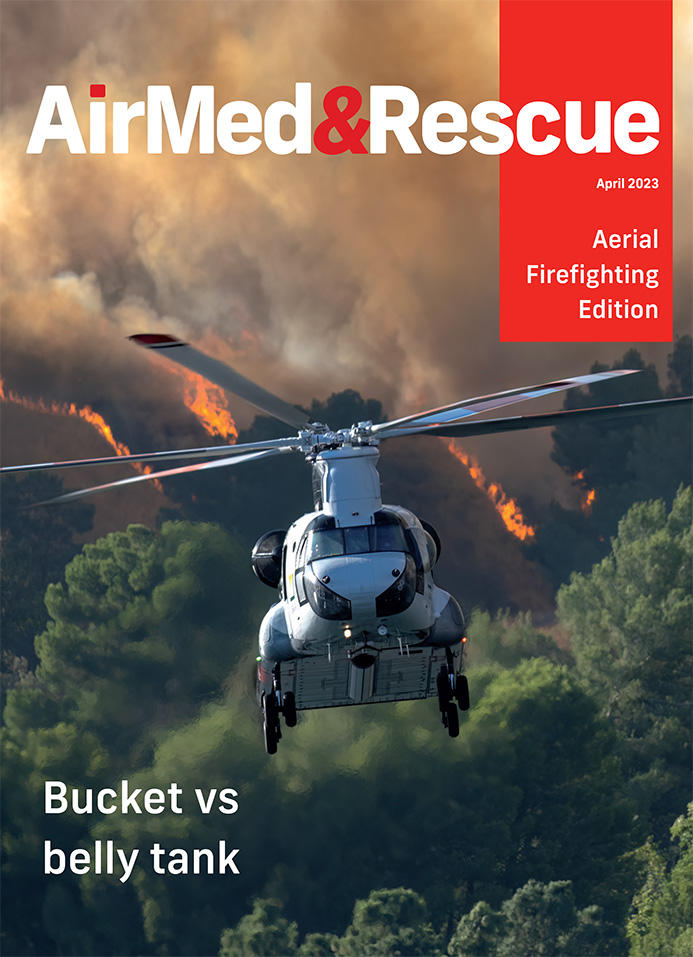

In the April 2023 aerial firefighting special issue

When preparing for a fire season, what are your choices for the type of fleet contracts you will use; location, situation, capacity, and a multitude of other considerations need to be made when deciding whether it is best to use a belly tank or a bucket, and what is the alternative; data collection and analysis have become more and more important when managing an attack on a wildfire, what software and equipment is available, and how can you manage integration and communication to improve your effectiveness in fighting fires; plus a whole lot more to keep you in the loop and in the air.

Jon Adams

Jon is the Senior Editor of AirMed&Rescue. He was previously Editor for Clinical Medicine and Future Healthcare Journal at the Royal College of Physicians before coming to AirMed&Rescue in November 2022. His favorite helicopter is the Army Air Corps Lynx that he saw his father fly while growing up on Army bases.