Industry voice: Going further for the smallest patients

Neonatal specialist Dr Carlo Bellini shares his insights into the need for, and practicalities of, providing safe helicopter neonatal transport for transfers of over 100 miles

The concept of a 100-mile limit for the effective use of helicopters in air medical transport, including neonatal transport, is well established. It is supported by reputable reference books, such as Principles and Direction of Air Medical Transport, published by the Air Medical Physician Association (AMPA; USA), and Guidelines for Air and Ground Transport of Neonatal and Pediatric Patients, published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP; USA). These guidelines suggest that beyond this distance, it may be more appropriate to utilize fixed-wing aircraft for medical transport. Originating in North America, this concept has been widely adopted and accepted by colleagues around the world, including the Royal Flying Doctors of Australia.

Adaptations within accepted guidelines

While accepting the authoritativeness of the cited sources, I believe that we must make some considerations that originate from the important geographical differences that exist between North America and Australia when comparing these territories with Europe. I believe Figure 1, which in the upper part shows some geographical areas photographed at night from space, and in the lower part the comparison between the territorial extensions, is illustrative of my point.

As can easily be observed, in North America, apart from large metropolises – New York, Chicago or Los Angeles – which are well lit, very little else can be seen. Even Canada is practically in darkness, as is most of Australia. On the contrary, in Europe there are almost no dark areas, if we exclude the northern part of Scandinavia and a few other small areas, such as northern Scotland. Italy, the UK and the Netherlands shine in intense yellow and look like football stadiums ready to host a great league match! The lower part of the figure clearly highlights the enormous differences relating to territorial extension, which becomes even more relevant if we consider each individual European country and not Europe as a whole. But what does all this have to do with the 100-mile limit?

Geographic anomalies

To answer this question, it is necessary to note that Europe often has a combination of large cities and numerous small urban villages, many of which retain a historic structure. These small towns are often densely populated and have hospitals with Level 1 maternity wards. As a result, it is not unusual to transfer a seriously ill newborn to a higher level of care. It is important to underline that in the vicinity of these birth centers, there are usually Level 3 neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

Although there are local differences, in most European countries the organization of birth centers is based on the hub-and-spoke model. In Italy, for example, the average distance between hub and spoke is

In most European countries, the organization of birth centers is based on the hub-and-spoke model

around 17–18 miles. The percentage of transport by helicopter is 1.7 per cent of the total (2021 data), comparable to the larger European countries, whose levels stand at around 1.5 per cent and two per cent of the total number of transports. The fragmentation of birth centers and related NICUs due to the high population density typical of Europe, as the night photography from space clearly indicates, explains why ground medical transport is substantially dominant in Europe.

Unique regions require different solutions

Without going into the specifics of each individual European state, some particularities are worthy of mention. The situation in Sweden, for example, is similar to North America. In the few urban areas (south Sweden), neonatal emergency transport services (NETS) are mostly carried out using ground ambulances, as in continental Europe; the four northernmost regions, sparsely populated, share two aircraft equipped for, and dedicated to, NETS. So in the northern regions of Sweden, as in the great wild spaces of North America or Australia, there is little place for helicopters. Despite these observations, however, a distinction must be made.

Returning to the Italian situation, with which I am obviously more familiar, although NICUs are widespread throughout the country, highly specialized centers for particular pathologies are – in reality – not. I am thinking, for example, of neonatal cardiac surgery, neonatal neurosurgery, centers dedicated to the treatment of diaphragmatic hernias, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. In Europe, these highly specialized activities related to neonatology are generally centralized. For these cases, obviously, the nearest NICU may not be adequate to cope with a complex patient. Hence, an air transfer may become necessary, even well beyond the accepted limit of 100 miles.

At this point, the reason for the nocturnal image becomes even clearer, as it illustrates how high the population density is in most of Europe. Many small towns do not have an airport near the hospital that may require a neonatal transfer. There would, therefore, be a need for a long ground transfer to reach a suitable airport, then make the flight with fixed-wing aircraft, and then make a further ground transfer to the final destination. In a time-critical transfer situation, this approach would result in too many problems, too much time, and, in reality, too many risks. As such, door-to-door transport by helicopter becomes much more effective. But only by taking the necessary precautions.

When HEMS is the right option, do it right

The idea for addressing this delicate point, ie how to extend NETS by helicopter beyond 100 miles while maintaining safety conditions, comes from a study carried out by Leonardo Helicopters and the Polytechnic of Milan.

In summary, the study addressed helicopter transport to oil platforms by applying the Extended-Range Helicopter Operational Standard (EHOPS) concept – which was in turn derived from the well-known Extended-Range Twin-Engine Operational Performance Standards (ETOPS). Without going into the specific detail of this important study, we have derived some interesting points to apply to our NETS. Both ETOPS and EHOPS refer to possible mechanical failures of the aircraft, therefore considering possible alternative airports. But when thinking about an air medical transfer, the possibility must also be taken into consideration that a forced landing could be required in the event of a sudden and serious deterioration in the clinical condition of the transported patient, or a malfunction of the medical equipment in use.

The identification of a NICU equipped with NETS can become decisive in the event of further support for the patient

The density of NICUs scattered throughout the area allows us to chart a safe route that takes into consideration the possibility of a forced landing, to be foreseen, if possible, in a hospital that can intervene. And even in the event of a forced landing outside the field and far from a hospital with an equipped helipad, the identification of a NICU equipped with NETS can become decisive in the event of further support for the patient. Therefore, taking into account cities with hospitals with both NICU and NETS allows us to trace safe routes should a forced landing occur.

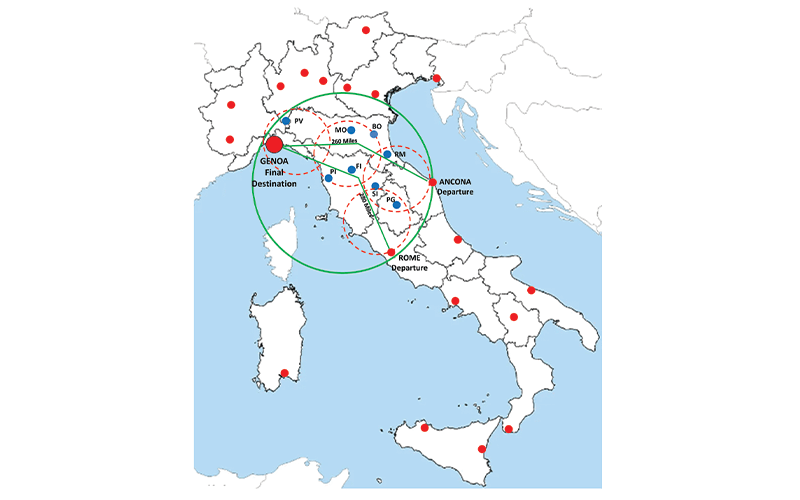

Figure 14 illustrates examples applied to two neonatal transports carried out by our service with a request for pickup of one newborn in Rome and a second in Ancona; both transports left from Genoa, home to the Gaslini Hospital, our headquarters, with a round trip. The map indicates the cities with NICU and NETS (blue circles) that have been considered to trace a safe route.

The safety range, the radius of the circle within which the helicopter can fly without refueling, is obviously highly variable

The safety range, the radius of the circle within which the helicopter (for example, an AW139) can fly without refueling (green line), is obviously highly variable; it depends on the helicopter model, the conformation and equipment in terms of fuel tank(s) and the configuration of the crew and equipment onboard. Including at least one NETS-equipped NICU in eachcircle on the map is obviously essential. The concept according to which a medical transfer by helicopter should take place without refueling stops, in my opinion, is not a binding concept. Even considering one or more refueling stops, the overall transport time can remain competitive when compared with the use of a fixed-wing aircraft in the absence of a quickly accessible airport, and obviously always widely favored in comparison with ground transport.

AirMed&Rescue is read all over the world. Canadian or Australian colleagues may disagree with this proposal; the use of aircraft is obviously highly advantageous, useful and, I might say, indispensable in sparsely populated and extremely large areas. But in a context that often occurs in Europe, difficult orographic areas, often mountainous as happens in Italy, and obviously with a high population density, a different approach – done safely – to the use of the helicopter for longer neonatal transport can, in my opinion, find space for application.

Weighing up your options

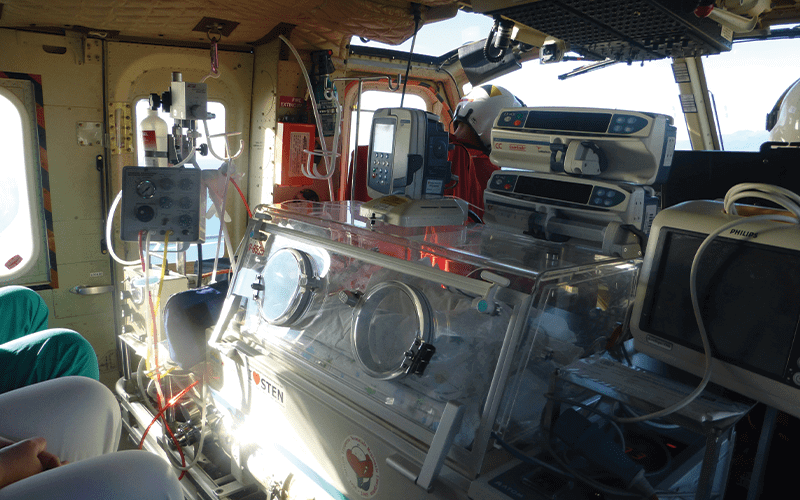

Our transport team is made up of a doctor, nurse, equipped incubator and support bag.

The incubator is obviously equipped with a ventilator (at least one, but we use two for transporting twins), cylinders, monitors, pumps; everything can be enriched with other equipment of your choice.

Weight:

- Crew (doctor and nurse) approximately 150kg

- Bag approximately 15–20kg

- Incubator, various possible solutions:

- Figures 2–10: medium equipment, around 100kg, best compromise between weight and completeness of the equipment (helicopter in pictures is the AB412)

- Figures 11–12: heavy incubator, latest generation, highly equipped, more suitable for ground transport, approximately 150kg (AB412 helicopter)

- Figure 13: essential, light incubator, approximately 60–70kg suitable for small helicopters; in this case AW109.

January 2024

Issue

In the January/February edition, we get swept along by swiftwater rescues; we land upon the qualities that make good helipads; we monitor the rise of HUMS on mid- and light-weight aircraft; and we channel the recent advances in avionics; plus more of our regular content including a heart-warming air ambulance case study for the new year

Dr Carlo Bellini

Dr Carlo Bellini is a Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Genoa. Since 1995, he has been part of the Neonatal Transport Service at the Gaslini Institute in Genoa, and in 2010 became Director of the Service. He is also Director of the International School of Neonatal Emergency Transportation – believed to be the first of its type in Europe. For more information, visit www.mcascientificevents.eu/ transportationschool