HeliResQ 2019 - event report

Sami Ollila, Vice-President, EURORSA - Rescue Swimmers Association, reviewed the recent HeliResQ – Nordic Workshop for AirMed&Rescue

The Finnish Border Guard Rescue Swimmer Association, in co-operation with Lite Flite, Ursuit and EURORSA – Rescue Swimmers Association, organized an event for helicopter SAR crew members that was held at Meriturva – Maritime Safety Training Centre from the 27 to 28 September 2019.

The HeliResQ – Nordic workshop consisted of a tribute to the rescue work conducted during the MS Estonia catastrophe, which occurred exactly 25 years ago on the day of workshops. The event covered physical tests of rescue swimmers, rescue gear, communication during a winch rescue operation, and standard operating procedures during mass casualty rescues from life rafts. Theoretical presentations and practical training briefs were implemented as part of practical training sessions at the Meriturva training pool and at a local swimming centre.

Sami Ollila briefing participants © Aleksi Mehtone

Workshop 1 – Rescue swimmer fitness

Report by Ben Darlington

President, EURORSA - Rescue Swimmers Association

The first workshop looked into helicopter rescue swimmers’ aquatic abilities and their ability to maintain a personal capability to respond to operational SAR missions. Individuals from lifesaving and other branches of aquatic rescue also took part in the trials to offer external feedback from fellow water-based professionals. Since their meeting in La Spezia, Italy in 2016, the EURORSA – Rescue Swimmers Association has been developing a fitness test, designed to best prepare their members for the stressors they may face during an operational mission. The HeliResQ workshop provided another fantastic opportunity to gather further data and feedback on the test.

The test is done continuously, with each serial simulating something that a rescue swimmer may face on live operations. With members of the Association operating in sub-zero waters, from deep within the Arctic Circle, to warm sub-equatorial waters and everywhere in between, the test is performed in swimming trunks with gear including a mask, fins and snorkel, which are relatively common to all swimmers. This enables comparisons and competition to take place regardless of the member’s operational environment.

EURORSA RS PT – 600-m swim

- 200-m freestyle, climb out. (Designed to test and develop general swimming ability.)

- 200-m freestyle with fins, mask and snorkel, climb out. (To prepare members for swimming with the critical gear used by the majority of members.)

- 100-m fin kick with a 4-kg weight, climb out. (To simulate a weighted tow, of a survivor, or of swimming on the cable or with a Hi/Trail line.)

- 25-m swim with fins pushing the weight along the bottom of the pool, then a 75-m swim to the finish, climb out; clock stop. (To simulate apnoeic environments, when due to external factors, the swimmer is unable to breathe freely.)

In between each section, the swimmer climbs out of the pool to simulate the upper body strength required to pull oneself from the water up into a raft, onto a yacht or a drifting vessel.

With the data collected from this test being examined and combined with the data gathered from previous meetings in La Spezia 2016 and Reykjavik 2018, findings will be presented at the next EURORSA Rescue Swimmers Meeting, in Cascais 2020. The Association is looking forward to publishing a guideline that will best prepare their members for operational missions.

The Rescue Swimmer’s Association wishes to remind readers that all tests were conducted under close supervision. Due to the dangers of shallow water blackout, underwater training should never be conducted without professional supervision.

Darren Craig (Lite Flite, SAR Specialist) presented a workshop about rescue swimmer harnesses equipped with a quick release device © Aleksi Mehtone

Workshop 2 – Quick release

Report by Kim Germishuys

Secretary, EURORSA – Rescue Swimmers Association

Lite Flite was invited as one of two main partners to arrange HeliResQ. Thomas Knudstrup (Lite Flite, CEO) and Darren Craig (Lite Flite, SAR Specialist) presented a workshop about rescue swimmer harnesses equipped with a quick release device.

The presentation looked specifically at how a Rescue Swimmer can release themselves from the hook in an emergency, while the cable is under tension.

In research conducted by Lite Flite, it was estimated that around 60 per cent of SAR helicopter operators around the world use a quick release device. The other 40 per cent rely on the hoist operator and pilot’s reaction time to hit the cable cut switch, hopefully within a time that will result in minimal implications for the person on the wire. The choice of implementing a quick release device into harnesses gives the rescue swimmer or person on the wire the ability to separate from a taught cable at a time of their choosing.

Participants at HeliResQ were given the chance to test out the Lite Flite Quick Release Box (QRB) over water, and practise optimal positioning for a fall while activating the quick release device under tension.

Workshop 3 – Drysuits

Report by Sami Ollila

Mika Aitio (Sales Manager) and Linda Granberg (Head Designer) from Ursuit were the other main partners with HeliResQ, who presented a general overview about how a drysuit is manufactured, and how Ursuit responds to the needs of its customers. Ursuit’s strength in the industry is cost-effective customization. Customer specifications are not always easy to interpret, so a continuous dialogue between the manufacturer and end user is often needed to provide the specifications. Mika presented several examples of customer-based innovations and about implementing customization requests by respecting the needs of their customers.

Ursuit was one of the very first companies to partner with EURORSA - Rescue Swimmer Association.

© Aleksi Mehtone

Workshop 4 – Operational communication

Report by Sami Ollila

Workshop 4 combined operational communication with a practical winch rescue simulation from life rafts. David Betts of All Elements Protection presented the Polycon wireless intercom system from Axnes, who provided all the necessary equipment for communication during the simulation. In his presentation, David also highlighted the importance of being prepared with other means of operational communication, like hand and/or light signals and ensuring that these signals can be clearly understood during night-time operations.

A wireless intercom system enhances situational awareness, especially for rescue swimmers

A wireless intercom system enhances situational awareness, especially for rescue swimmers, when compared to that of the traditional radio communications such as using a hand-held VHF radio. By being connected to the helicopter’s intercom system, the rescue swimmer is ‘in the loop’ throughout the operation. This generates a lot more reaction time for the rescue swimmer, in case of a critical malfunction in the helicopter or a malfunction during the winch operation.

The facilities at the Meriturva Maritime Safety Training Centre enable ‘scenario builders’ to replicate conditions close to those a rescue swimmer would experience during an operational mission. With wind and swell generators creating sea chop, black-out lighting conditions, along with speakers which can drown out normal audible conversations, adding in thunderstorms and helicopter noises into the mix, it was the ideal location for a large-scale ‘scenario exercise’ to take place.

The rescue swimmers were tasked with recovering four people from a life raft. Each of the survivors had triage tags, with two being fully ambulant, while the third was moderately ambulant and the fourth was completely incapacitated.

The centre was initially blacked out and swimmers were able to compare different verbal and non-verbal signals and work through different recovery methods, from accompanied recoveries in the single and hypothermic strops, through to implementing the hi-line and guide-line ring set ups. With rescue swimmers from 13 different nations taking part in the exercise, including three who had been a part of the MS Estonia rescue, the practical exercise was an opportunity to compare operating procedures, share techniques and learn from past experiences.

Risto Leino at one of his last flights before retirement. Photo © Lloyd Horgan

MS Estonia catastrophe – A mass casualty rescue

Report by Ben Darlington

Rescue swimmers Risto Leino, Patrik Nilsson and Thorbjörn Olssen gave unique and at times, emotional, presentations about the rescue efforts during MS Estonia catastrophe.

With so many survivors in so many rafts, rescuers had to be ruthless in order to rescue as many people as possible, a fact that weighs heavily on those involved

The MS Estonia sunk on the 28 September 1994 after her bow door failed in rough seas whilst travelling from Tallin, Estonia to Stockholm, Sweden. The final report on the tragedy estimates that of the 989 persons on board, 310 made it to the outer decks before the vessel slipped below the water at 01h50. With the water temperature no more than 11°C and winds up to 40kts, by the time the first Finnish Rescue Helicopter arrived on scene at 03h05, it is thought that a third of survivors had already been lost to drowning or hypothermia. With no persons recovered from the water alive after 09h00, between 03h00 to 09h00, Swedish and Finnish helicopter rescue crews raced against time to rescue as many people as they could from the frigid Baltic waters. With so many survivors in so many rafts, rescuers had to be ruthless in order to rescue as many people as possible, a fact that weighs heavily on those involved.

Swedish Rescue Swimmer Patrik Nilsson recounted how on arrival at the rafts, he was confronted with multiple victims in various stages of advanced hypothermia. With the rafts being tossed about in waves up to 20ft and reduced dexterity for rescuers, being able to definitively determine who was alive and who wasn’t was extremely difficult and ultimately, it came down to the intuition of an individual rescue swimmer. Nilsson lamented that helicopter crew members, and especially the rescue swimmers, have struggled with the thoughts of whether they had left someone behind that was possibly alive at that moment when the rescue was at hand.

A further unique challenge was the number of life rafts in the area during the early stages of the rescue. With rescuers forced to leave the deceased in rafts and move on in order to rescue as many people as possible, there were occasions of individual rafts being checked multiple times by different crews.

With rescuers forced to leave the deceased in rafts and move on in order to rescue as many people as possible, there were occasions of individual rafts being checked multiple times by different crews

With the evolution of infra-red technology becoming more common in SAR aircraft over the past 25 years, this would have assisted in such situations. Whilst rafts have serial numbers and/or service cards on or in the raft, these are unreadable from an aircraft in a hover. During a discussion by attending rescue swimmers, a few ideas were exchanged on how marking a raft that had been checked could be carried out:

The last two digits of the raft’s serial number could be displayed in a large font on the canopy and underside of the raft. (On the morning of the 28 September, many of the rafts had capsized due to the rough conditions, and survivors had scrambled onto the floors of the over-turned rafts).

Sea marker dye could be smeared on the canopies of the rafts. Those with experience with sea dye can attest to the manner in which it stains material, and trials of this approach by the Estonia Police Airwing have proved positive.

While the MS Estonia tragedy was an unprecedented maritime disaster in European peacetime waters, Rescue Swimmer Risto Leino did find comfort in the fact that he had the opportunity to save people from the cold Baltic Sea that night. Leino went on to acknowledge his colleagues, who subsequently worked long hours recovering bodies from life rafts and the ocean. For future reference, Leino urged every SAR crew present to go out and train when the conditions are hard. At the end of the day, it is in these conditions that you really have to be able to perform as a crew.

A learning experience

Sami Ollila summarised the event: “The HeliResQ – Nordic Workshop enabled interaction and dialogue between helicopter SAR crews and existing partners who were able to share experiences and learn through the workshops and informal interactions. We believe it is important for meetings like HeliResQ to be arranged. Direct interactions and sharing of ideas between colleagues about rescue gear and implemented procedures may be an effective way to implement improvement processes in the operational sector of different organizations. It’s equally important to be able to meet your colleagues internationally and to have an opportunity to make lifelong friends from another corner of the world who understands the line of work you do.”

Source:

The Joint Accident Investigation Commission of Estonia, Finland and Sweden (1997) Final report on the MS Estonia disaster of 28 September 1994.

November 2019

Issue

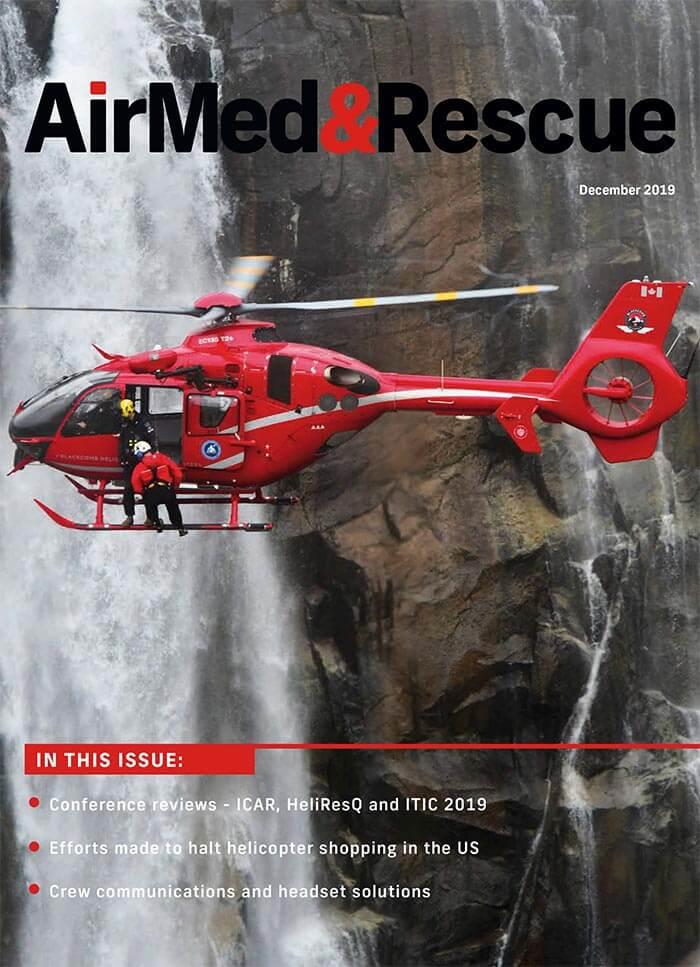

In this issue:

•Conference reviews: ICAR, HeliResQ and ITIC Global 2019

•Avionics upgrades breathing new life into aircraft

•Optimising rear crew communications in rescue helicopters

•Efforts made to stop helicopter shopping in the US air medical market

•Latest IFR regulation changes by the FAA

•Provider Profile: Scotland’s Charity Air Ambulance

Sami Ollila

Following his conscription with the Finnish Navy as a mine clearance diver, Sami was accepted for the helicopter rescue swimmer training program at Finnish Border Guard - Air Patrol Squadron in 1996. Sami graduated with a Bachelor of Healthcare in 2018 and now holds a dual-role position as a Rescue Swimmer and a Paramedic, in the five-man crew of H215-Super Puma helicopter. Sami currently volunteers as the Vice president of Rescue Swimmer Association and as an instructor at Finnish Swimming Teaching and Life Saving Federation.