Should marine rescuers on the hoist stay connected to the cable or swim free?

Rescuers lowered from a helicopter to pick people from the water can stay connected to the hoist cable or swim freely. Femke van Iperen explores how and why each method is used by military crews around the world.

When a military SAR helicopter crew performs a rescue mission at sea, typically one of its crew members will be lowered into the water by a flight engineer, mechanic or hoist operator,via a harness or sling. This rescue swimmer may unhook themselves from the hoist cable and swim freely, or they may stay tethered to it. With pros and cons to each method, there’s a lot to consider in terms of crew and victim safety.

Procedures around the world

Over in Canada, a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) search and rescue technician (SAR tech) can, depending on the situation, remain tethered or swim free

Like most rescue swimmers, US Navy aviation rescue swimmers (AIRRs) have to undergo ‘intense physical and mental training’ in order to work in ‘some of the most extreme environments imaginable’. They are trained to conduct rescues both hooked and unhooked, so that they can adapt to the demands of each mission. “For example, we would stay attached to the hoist cable when performing a mountain or cliff rescue, or a cold-water rescue for quick extraction, but we would detach from the hoist cable when rescuing a survivor in a parachute in the open ocean”, says US Naval Air Crewman Helicopter Chief Roger Richards, who is a training chief petty officer at the Aviation Rescue Swimmer School in at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.

Over in Canada, a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) search and rescue technician (SAR tech) can, depending on the situation, remain tethered or swim free, explains RCAF Master Warrant Officer (MWO) Darryl Cattell, a SAR tech staff officer at 1 Canadian Air Division Headquarters. SAR techs, highly-skilled rescuers with the training to work across a wide range of terrains and weather conditions including Canada’s Arctic region, must make a decision on the spot which procedure to follow.

Although the procedure chosen may ultimately depend on the situation, sometimes military SAR rescue swimmers will follow one particular method under ‘standard’ operating circumstances. In the Greek Air Force for example, during a standard rescue operation, the rescue swimmer stays attached to the winch line, says Lt Junior Grade Giannikos Ioannis, a Greek Air Force helicopter rescue swimmer and instructor. “During this procedure, the time needed and the risk of losing the rescue swimmer are minimised”, he adds.

“The priority for all SAR winching operations would be for the wireman or surface swimmer to remain attached to the rescue hoist if the scenario permits,” Warrant Officer Aircrewman Steve Cheeseman says of Royal Australian Navy rescue swimmers. He also explains they should be able to detach themselves if needed, and that they should leave the rescue strop attached to the hook to provide means of recovery.

In the US Coast Guard (USCG), it’s standard procedure for the rescue swimmer to disconnect from the hoist cable or winch line, T2 Chad Watson, USCG helicopter rescue swimmer and aviation survival technician, says. Nonetheless, USCG rescue swimmers are trained to conduct both procedures and there are non-standard scenarios when the swimmer stays connected, otherwise called a ‘direct deployment’. To avoid injury or damage in case of an emergency during such a mission, the rescue swimmer can also choose to disconnect from the hoist hook, says Watson.

In the US Coast Guard (USCG), it’s standard procedure for the rescue swimmer to disconnect from the hoist cable or winch line

The pros of unhooking

There are some benefits that only unhooking can bring. An example is when a rescue swimmer has to spend a long time performing first aid or immobilising a patient, for example. In such cases, says Ioannis, it may be better to ‘unhook, finish the work while the helicopter is flying in a safe position, and call the helicopter for the lift-up’.

Richards further explains that being able to swim freely means there is no chance for the rescue swimmer or survivor to become entangled in the hoist cable, and that rescue swimmers will be able to perform an underwater approach – by swimming under a panicking survivor and placing them in a controlled cross-chest carry after surfacing on the other side of them.

At other times, a rescue swimmer may need to board a sailing vessel, whose tall mast, rigging and equipment would impede an attached swimmer’s safety, says Watson.

Cheeseman also explains there may be a requirement for the aircraft to move clear of the winching position, reducing noise and downwash issues at the rescue site. In addition, disconnecting from the cable can ‘allow the swimmer to communicate with persons being rescued and provide assistance’, he says.

The pros of staying connected

There are situations when a rescue swimmer should remain tethered, and for Richards, who explains it can take five to 10 minutes to get re-attached to the hoist cable once detached, ‘it is typically faster to remain hooked to the winch line, and would result in a quicker recovery on a surface-water rescue’.

To which Watson adds: “A disadvantage to unhooking is the possibility that the rescue swimmer cannot be recovered, possibly due to injury, damage to the aircraft, or a loss of visibility or communication with the rescue swimmer.” He comments that there are, however, ‘redundancies, back-up systems and equipment in place to greatly reduce this possibility’.

As a separate solution, in some cases a disconnected RCAF SAR tech may still be connected via a guide line. “This rope serves as a life-line tethered to the hook on the hoist cable, which pays out as the SAR tech swims to the objective – maybe on a small, unstable vessel like a sailboat or a life raft”, Cattell says.

Saving lives

It may be a standard USCG procedure for a rescue swimmer to disconnect, says Watson, but ‘the ability to deploy and deliver a rescue swimmer in multiple ways increases the possibility of a successful rescue’. He continues: “The environment in which the rescue is attempted, on-scene conditions and capabilities of the crew and aircraft, as well as the authorisation and approval by the overseeing organisation, would all be determining factors in deciding which manoeuvre could be used to effectively execute a rescue.”

Echoing this summary, Cheeseman notes: “Royal Australian Navy rescue swimmers have to be prepared for every scenario, which may require a different plan due to platform, sea state and obstructions.” Ioannis adds: “The rescue swimmer’s choice to stay hooked or unhook depends on the terrain (such as open sea, floating obstacles, ship’s decks, cabins, holds, rocky seaside, steep mountain sides), the type of rescue equipment and the condition of the victim.”

Relating the same conclusion to the ‘expanse, elevation, ruggedness and remoteness over the bodies of water across Canada’, Cattell explains: “Our SAR techs must factor in all the elements every time, and for an RCAF SAR tech, the decision to hook or unhook is guided by the nature of the mission such as the environment, the location at sea, the weather conditions, the height of the hoist. Basically, in every situation, SAR techs would first assess the rescue on its merits, including the environment, patient condition, and what resources are available.”

So, it seems that although for some military SAR services there are standard procedures for rescue swimmers to remain tethered or not, it depends on the situation, and each technique offers pros and cons in different scenarios. Or, as Cattell puts it: “Procedures, techniques, equipment, language and terminology may not necessarily be the same, but what is common to all the countries, with certainty, is saving lives.”

March 2016

Issue

In this issue:

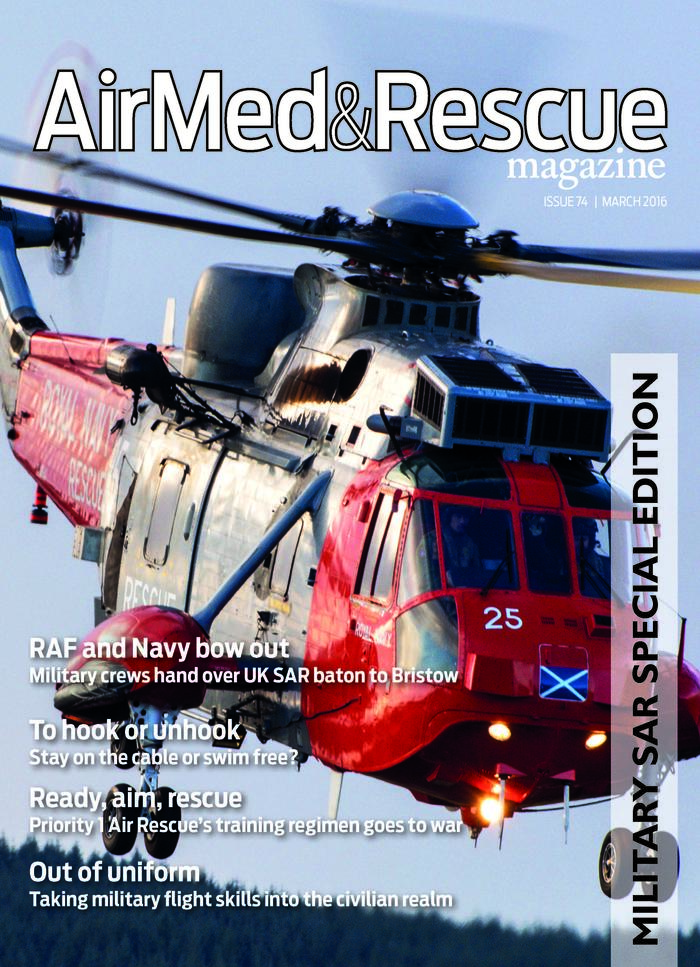

RAF and Navy bow out - Military crews hand over UK SAR baton to Bristow

To hook or unhook? Stay on the cable or swim free?

Ready, aim, rescue - Priority1AirRescue's training regimen goes to war

Crew resource management

Interview: Kevin Weller, Chief technical rearcrew, Bristow Helicopters, HM Coastguard Caenarfon SAR

Aircraft Spotlight: Quest Kodiak 100

Femke Van Iperen

Femke van Iperen is a freelance bilingual journalist. Since graduating for a postgraduate diploma at the London School of Journalism in 2003, she has been writing background features for a variety of commissioning and international clients, in both Dutch and English. The magazines she writes for are read by global, mixed readerships.