The challenges of operating civilian SAR and HEMS in Latin America

Chris Sharpe shares his experiences on the unique challenges and risks he faced when starting up a civilian search and rescue organisation in Central America

When someone talks about a Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) or Helicopter Search and Rescue (HSAR) unit, we tend to imagine the following: individuals who are highly trained and specialized in their relevant field wearing their appropriate personal equipment, riding helicopters that have medical equipment onboard that has been designed with the aviation environment in mind, and which are ready to do the mission during the day, and sometimes during the night. This mission may sometimes involve hoist rescues or may sometimes even involve the crews having to undertake some instrument flight rule (IFR) flight time. In our minds, these individuals and their helicopters are also operated in accordance with all the relevant standards we come to expect.

It has been my experience that this is not what you get when you look at HEMS and SAR in Latin America. Not including the offshore installation providers, outside of some units (I know of the Relampagos Helicopter Rescue Team in Mexico, who have received some support by Priority Air 1 Rescue for a number of years now, as well as the recent crew training in Belize done by Air Rescue Systems), the chances of finding a full-time professional HEMS / SAR crew available to the general public is, at best, not high.

Central America has the largest concentration of privately owned helicopters in the world, with the Bell 206 model and its variants being the most common airframe

Being the former project manager for the HeliSOS helicopter air ambulance / rescue service in Guatemala, and currently being involved in a number of SAR projects in Guatemala, EL Salvador and Peru, in this article, I will attempt to explain some of the reasons behind this phenomenon.

It’s been my experience that the three biggest hurdles to overcome in setting any such project up are:

- Cost

- Culture and ego

- Lack of regulatory enforcement

Central America has the largest concentration of privately owned helicopters in the world, with the Bell 206 model and its variants being the most common airframe. So, the usual answer when starting some type of medical service involving helicopters is ‘I have my own helicopter, if anything happens and we have wounded people, I will get my helicopter and fly them myself, so I don’t need to pay any extra cost per hour for medical equipment, as it isn’t needed, since all helicopters look the same’.

This means that no consideration is given to the actual capabilities, qualifications and standards of the people and equipment inside. Why add the expense of cardiac monitors, infusion pumps, point of care ultrasound, transport ventilators and medical personnel with advanced international qualifications and understanding of gas laws and flight physiology, that can stabilize a patient at the point of injury (POI)/ under resourced remote hospital with vasopressors, FAST scans, tranexamic acid, rapid sequence intubation and the plethora of modern pre-hospital medicines, when you can get a local volunteer ‘first aider’ to hop on and just utilize some bandages and a bag valve mask (BVM) for the 45-minute flight – often at no extra cost? (local firefighters are typically happy to take a helicopter ride).

The disparity in equipment and training further aggravates the fact. Because the sending facilities are used to under-equipped and under-trained ‘medical professionals’ arriving, many a patient is withheld by the doctors as ‘unstable to travel’. Many flight requests are therefore delayed / cancelled to professional, well-equipped teams, so there is a high morbidity rate amongst patients that is directly attributable to this culture of misunderstanding.

Lack of medical malpractice laws, and the total non-existence of legislation like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), or even Case Law such as Barris v County of Los Angeles 1997, mean that this trend continues, as opposed to a patient benefit vs risk approach to medical care.

Those that can afford to financially support a rescue helicopter operation, have their own. Those members of the public that would benefit from these services are well below the poverty line and cannot afford it. In Guatemala, we are restricted to an older model Bell 206L Long Ranger, not because there aren’t any other, more suitable, helicopters available, but they are all either privately owned, have a higher cost of operation (which no one wants to pay), or have other, ‘more important’ duties.

If the flight is authorized by an insurance company that requires the services, then unfortunately cheaper is better, to retain profit margins. For example, I was the project manager for the first air ambulance service in Guatemala that operated to an international standard, but I couldn’t use it myself, as I have personal medical insurance, and would have to go through their system to get medical attention, including air transport (and cheapest wins, if it is authorized at all). And if I wanted to use my own service, I would end up with an astronomical hospital bill, since I didn’t ‘follow the system’.

SAR operations are usually conducted the same way: whenever an aircraft goes missing, a group of individuals, usually members of a private aviation club (usually the same aviation club the missing aircraft is part of), with zero training in SAR mission planning, crew resource management (CRM), search patterns, or even what to look for, get together, decide where the lost aircraft ‘should be’, and launch. If an observer is carried at all, most of the time it will be whoever is around at the club and will have zero training on how to conduct a search. If the country’s civil aviation administration is involved and plans the operation, sometimes the club members will argue that the person in charge does not know how to conduct a SAR operation, does not have ‘X’ amount of hours or experience, or does not have enough assets. Club members have been known to blame the administration if they are not allowed to participate, and tragedy strikes. If everyone is allowed to participate, and the lost aircraft is found, ground units of firefighters, military and police are then directed to the site as required, as opposed to requesting the assistance of a professionally trained crew that has the necessary training, equipment and ability to take a portable ICU directly to the patient if required, because that involves an extra cost that is ‘not actually needed’.

Club members have been known to blame the administration if they are not allowed to participate, and tragedy strikes

To put this into context, my own crews have been called throughout Central and South America, usually very late into the scenario by either an embassy, international family member or international insurance company, and we statistically find 86 per cent of victims within a relatively short period of time, exactly where our mission planning tells us to look. Unfortunately, due to the timeframe involved, by the time someone cares to involve us, we find the occupants of the missing aircraft are normally deceased.

Another major problem that is faced by crews themselves is that some of the larger helicopter companies don’t understand what a professional HEMS or SAR crew can do, as they have no experience with HEMS / HSAR operations under the international standard. So, there is a legacy of relying on ‘whoever is available’ to man the aircraft. Only a handful of private pilots who have first-hand experience of true HEMS and SAR operations invest in their own training and personal equipment. Even some ex-military pilots have no real idea of what the value of having a properly trained crewmember is, since some militaries in the region are less interested in training their non-pilot crewmembers than the pilots, and most crewmembers do not have training beyond basic aircraft maintenance, and are not allowed to contribute as part of the crew (when questioned during some operations, some military crewmembers have said that they don’t even know what the mission they are doing is).

Challenging terrain for aircrew and aircraft alike © Chris Sharpe

Companies may have a manual of procedures that allows training flight time, but this is very rare. Manuals with provisions for crewmen are rarer still. There is almost always no contractual obligation to the medical or SAR crew, since they are not usually directly employed by the helicopter company, and their prime concern is their own helicopter and pilot. Usually, helicopters already have a VIP flight or some other mission scheduled as soon as we finish the HEMS / SAR operations (which also means little, if any, special equipment can be added to the helicopters, and none of it permanent, so very few helicopters in the region have external cargo hooks, and even fewer have hoists).

The service isn’t provided for free – no money, no helicopter

This was a recent occurrence for one of my rescue crewmen in Peru. During a mission where he rescued 25 people in one day during recent landslides, he gave his seat to the last survivor, and the helicopter never came back. After six days surviving in the jungle at an extreme altitude, he was able to signal a military helicopter, which luckily landed and collected him.

So, why don’t we have a state-funded system in most of these countries? Usually, this question is answered by one simple word: corruption.

You could set up, equip and train the best team in the world, but you would be then replaced by ‘a friend’ who can do it cheaper, at a lower standard, but still retain the original ‘image’. Or when a new president is elected and everyone from the previous term gets arrested, you and your team must either join them, leave the country, or become informants. Even if none of this happens, civil aviation authorities are usually among the team that changes with each new government administration, so your whole team gets the boot, and no more state HEMS / SAR unit.

Peru, extreme altitude © J McSparron, Black Wolf Helicopters

ICAO Annex 12 (Search and Rescue) states: “2.1 Search and rescue services. 2.1.1 Contracting States shall, individually or in co-operation with other States, arrange for the establishment and prompt provision of search and rescue services within their territories to ensure that assistance is rendered to persons in distress. Such services shall be provided on a 24-hour basis.”

Many Latin American countries are signatories to this but, since the regulation does not specifically mention ‘air services’, a prompt service may mean an extensive ground search, protracted over many days due to terrain, altitude, weather conditions, and service availability.

Who else flies at night? Narcotic smugglers and people traffickers.

Plus, what many don’t realize, is that we don’t fly at night. Anywhere. Even including the military units, some of the Central / South American countries don’t fly night visual flight rules (VFR), let alone fly with night vision goggles. Some reasons are plausible, whilst others are not.

One reason is, who else flies at night? Narcotic smugglers and people traffickers.

They fly where they want, when they want, so if you fly at night, then you would probably face a welcoming committee (whether law enforcement or rival gangs) when you land. It is not uncommon for even military or police helicopters to be received at gunpoint by other law enforcement personnel when making any unscheduled landings (these misunderstandings are often resolved quickly). This is not necessarily true all the time, but it is a risk that needs to be mitigated. Sometimes, this mitigation can be done simply through applying for a night operating license with the local aviation regulatory body (although usually at an additional cost).

Another reason is lack of understanding and training associated with night VFR or even day IFR, as many aircraft and pilots are not IFR rated, since there is no requirement. Even if aircraft and pilots are IFR rated, there is often no regulatory framework to allow real IFR flying in rotary-wing aircraft (this is really an issue worldwide). If it is at all possible to allow night flight, a simple step of only flying to known landing spots that have been risk assessed by the crew during the day would be a way to alleviate this risk.

The main reason for not flying at night is far simpler. It’s the threat of a wire strike.

Throughout the region, the vast distances, and significant variance in altitude, combined with no real central reporting system to report wires and cables, and an indigenous population that just do what is normal to them (wires and other hazards usually appear overnight, and without any kind of markings, even if they are required by law), creates a very high-risk environment. A lot of companies do not even have a hazard map, and those that do, don’t usually update them. A survey of pilots in the region indicates that they mostly learn about new wires and other hazards through experience, or talking with other pilots, and even that knowledge is very localized depending on who is flying where. The threat of wires simply makes it a risk to the aircraft that no aircrew is willing to take.

Altitude itself is another factor that is often overlooked. If you found a means of funding a permanent helicopter and crew, fully equipped it as a HEMS or SAR aircraft in accordance with the best modern practices that are commonplace throughout the world, you then immediately limit yourself in your area of operations due to weight.

As an example, our operation in Cusco, Peru, is at approximately 11,300 ft MSL. That’s just the base altitude, before you even launch and go higher to fly an actual mission. The recent humanitarian event that saw my crewman stranded; he spent the rest of the day assisting the Mi17 Air Force rearcrews delivering supplies. Due to the altitude they were operating, the 4,000-kg internal cargo limit was reduced to 400 kg.

Minimum basic life-saving equipment © Chris Sharpe

So, what does the future hold for SAR and HEMS operations outside of services contracted directly to mining, oil and gas companies, or the extremely limited services the public can receive from the military?

A crucial and key part that is missing from the various aviation authorities is the practice of enforcement. Rules and regulations are often very out of date, or non-existent, and nobody enforces them.

In most parts of Latin America, aviation authorities have a search and rescue committee. If you are lucky, that is run by someone who has witnessed the ‘modern way’ of how HEMS / SAR helicopters should be operated. Their input, however, is unfortunately minimal. Powers of enforcement, ability to reprimand / remove a pilot’s license, issue a fine? Would not happen.

A crucial and key part that is missing from the various aviation authorities is the practice of enforcement

So, anyone can fly a rescue mission without training or equipment, and without fear of reprimand, why? If the SAR committee member tries to correct anything and ‘change the system’, they are simply replaced at the earliest opportunity for any minor ‘misdemeanor’, then due to corruption ‘someone better’ can replace them.

Revoke a pilot’s license? You may end up with a not-so-pleasant visit to your home and family, or even as you drive home by a paid ‘hitman’. You probably won’t survive that.

Besides, since the culture doesn’t see anything wrong with how the system operates, why fix what isn’t broken?

All of these are the reasons I set up my own company. Even then, I understand that a truly full-time professional helicopter rescue crew will probably not happen in my lifetime. I have personally tried online fundraisers for the Guatemalan summer weekend vacation at the beach (that has a fatality rate on average of 15 people drowning a day) and been involved in initiatives to make a full-time service affordable to families. However, because the poor are poor, the rich have their own aircraft and people dying is ‘one of those things’, they have never proved successful.

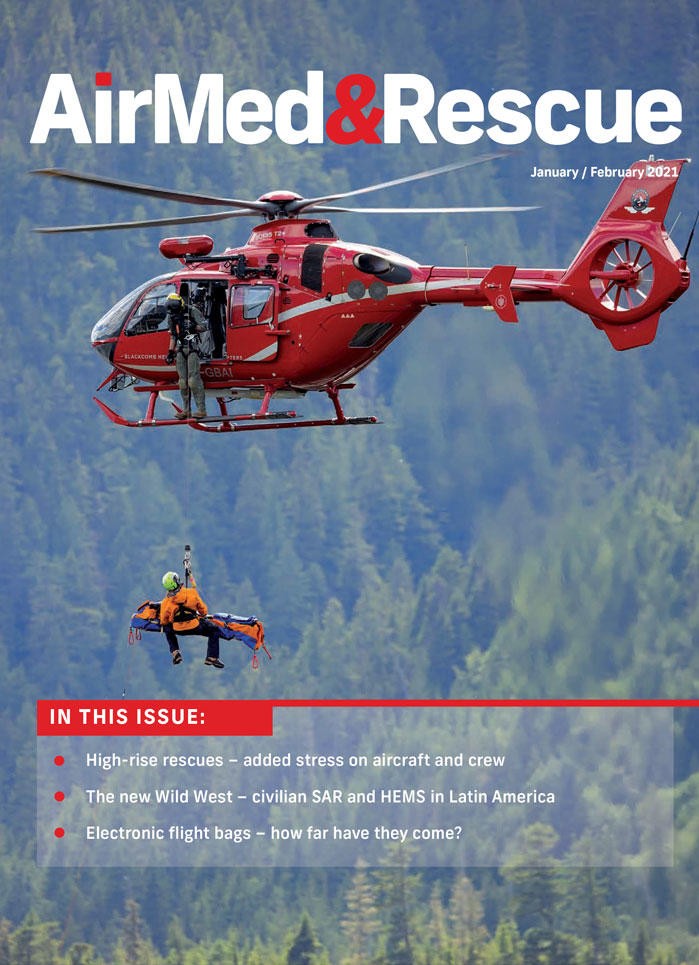

Priority 1 Air Rescue conducting hoist training in Mexico © J Segal

So, the most myself and likeminded aircrew professionals can do is maintain an operational currency in our own spare time and at our own individual cost so that are we still are available if the call is needed, but by earning our own living by way of training the pilots and medics on the basics of aircrew survival, wilderness medicine, SAR, so at least they don’t become a statistic themselves, as frustratingly, they will highly likely to be the ones that actually fly the mission and we will never be called.

Even training is difficult since, due to the average income, as soon as you add a helicopter into a training schedule, your course becomes ‘too expensive’ or ‘only for westerners’. It is a constant battle. The cost of basic rescue equipment is often way out of affordability, and large companies will not donate second-hand equipment for fear of litigation. So, most go without, or make do with what is available. “Well, we’ve always done it that way, and nothing has happened so far,” is a common thought.

My former project has the motto ‘the sound of hope’, but anywhere outside of the areas mentioned, you have no idea what standard is coming - or even if one is coming. But what is true is that you only hear any sound at all if you have a credit card.

January 2020

Issue

In this issue

- High-rise rescues: added stress on aircraft and crew

- The new Wild West: civilian SAR and HEMS in Latin America

- Electronic flight bags: how far have they come?

- Interview with Dr Duncan Bootland, Medical Director, AA Kent, Surrey Sussex

- Research into point of care tools for diagnosis

- EURAMI accreditation during Covid-19

Chris Sharpe

Chris Sharpe is a contributor for the education company Heavy Lies the Helmet. His experience includes Project Manager, Chief Aircrewman, and Flight Paramedic for HeliSOS HEMS/Rescue Helicopter in Guatemala, and the Chief Aircrewman at Black Wolf Helicopters. Sharpe has been flying for over 28 years; having over 15,000 flying hours and 6,000 rescue operations to his credit. He is a safety and survival expert, teaching survival techniques to both civilian and military helicopter crews in Guatemala. He is also the recipient of the HAI 2019 Salute to Excellence Safety Award.