Surviving a helicopter accident

Chris Sharpe, a safety and survival expert and aircrewman for HeliSOS in Guatemala, believes that having the right tools can be the difference between life and death for air crew following an aircraft accident

The aim of a survival kit is to give you the tools to enhance your chances of survival. They vary in many sizes; from a large aircraft jungle survival kit to a small personal tin. Depending on your location and weight restrictions, it may be as simple as a knife and fire-starter. Remember: You are only a survivor once you have returned to civilisation!

Most aircraft carry survival equipment depending on their role and location. This is usually required as part of your country of operation’s aviation administration legislation. However, regulations can vary dramatically.

Aircraft survival gear is often referred to as ‘ALSE’ from the military mnemonic:

- Aviation

- Life

- Support

- Equipment

ALSE didn’t really exist until after World War 1. At that time, survival gear was meant for ‘surviving the weather and the enemy’. Even parachutes were not issued; as they were deemed as ‘cowardly’. Hence, lifespan was a maximum of three weeks for an aviator during WW1 in 1917. As WW2 progressed and aircrews became better trained and more expensive to replace, the issue of survival gear became more routine. Life preservers (the classic ‘Mae-west’), parachutes and survival kits were issued. Thankfully, helicopters were invented (Sorry, fixed wing chaps!). ALSE started, not only to advance in technology, but also make us rotary wing types look good and super cool in the process.

The Korean War (the first extensive use of helicopters in aeromedical and transport roles) introduced the flying helmet and the ‘Barbour jacket’ project that improved a WW2 design (USAAF Type C-1 Emergency vest). That was the precursor of the modern survival vest that was extensively used in the Vietnam War. The vests were designed to allow the pilot to crash and run (literally for his life), and still have the gear attached that he needed whilst waiting for rescue.

Unfortunately, most companies would frown on you turning up for work wearing the latest generation Air Warrior gear. Many of our patients would also be slightly worried, so we have to balance our needs along with our company’s image. Working SAR services? Immersion suits, helmets, and vests are no problem and should be expected. Critical care transport from ICU to ICU? Probably not the image your company wants. However, it is all based on your operational tasking / risk assessment.

Survival kits

A jungle survival kit is carried on all our programmes’ helicopters here in Guatemala (in addition to a first aid kit). It is always worth spending a half day training on your kits; even if it’s just to see what is in it, and how you can use it effectively. Plus, this can also identify potential issues with your maintenance section seals used on kits. For example, a recent military unit sealed kits with wire and lead seals. Without a cutting tool, you couldn’t open it.

Unfortunately, in the event of a crash, dynamic rollover, fire or water ditching, you will probably not get a chance to use any of these aircraft kits. Why? Based on statistical fact, in the event of a crash, if it isn’t fastened to you, you won’t have it!

The first place to store your gear is your pockets. This prevents you from carrying too much. (Who doesn’t overstock their med bag?). My father used to carry a butane lighter, Swiss army pen knife, 20 Marlboro and a small bottle of whiskey. I’m not sure this fits the priorities of survival, but he was happy – bless him!

Whatever method you utilise, it needs to be small, compact and lightweight, so that you get accustomed to always carrying it on your person. All items need to aid in the priorities of survival:

- Protection – from the elements, weather, insects and further injury are all covered in this section.

- Location – we want to be found and be rescued

- Water – collection and preservation

- Food – not an immediate priority, but necessary to prevent hypoglycaemia and malnutrition.

Start small

The below are suggestions for kits, beginning with the smallest (and cheapest!) and progressing up the pay and size scale.

Survival tins

The ‘combat survival tin’ is a very popular choice for many people. Designed originally by the British Special Air Service (SAS), it is designed to sit in a trouser or jacket pocket. If the soldiers had, for whatever reason, discarded their rucksacks or webbing equipment, then they still had their tin on their person. They contain a few simple items, that with the correct knowledge, can assist in the priorities of survival. They can be commercially bought or home-made.

Go-packs

A modern evolution of the tin. Available through surplus stores, eBay, etc., go-packs are a cheap way of getting a sealed kit that you can use. Depending on the type, they can be large, but are usually very thin. They are designed to fit in the ejector seat base, and they are an additional back-up to the gear the aviator already carries on his person. Personally, I don’t worry about expiration dates too much since there is usually no food content, and everything is vacuum sealed.

If you decide to build your own tin or go-pack, some items for consideration may include:

- Small folding knife with locking blade

- Fire lighting steel, butane lighter, matches and small candle

- Mosquito head net (can double as small fishing net)

- Dry tinder for firelighting

- Unlubricated condoms for water collection

- Whistle

- LED microlight

- Paracord

- Small fishing kit

- Snare wire

- Safety pins

- Chest rigs

The chest rig was designed for infantrymen to carry more ammunition in a readily accessible place. MOLLE platforms are very popular with ground SAR teams. They also have the added advantage of being small, compact and don’t look too ‘gung-ho’. Easily customised, you can add a simple pouch for survival gear, pouches for essential med gear, radios, etc. The advantage of these over a full, top-of-the-range aircrew survival vest is that they leave your back free; not only for your med bag, but it is also a lot cooler in the hotter places that we work in.

Survival vests

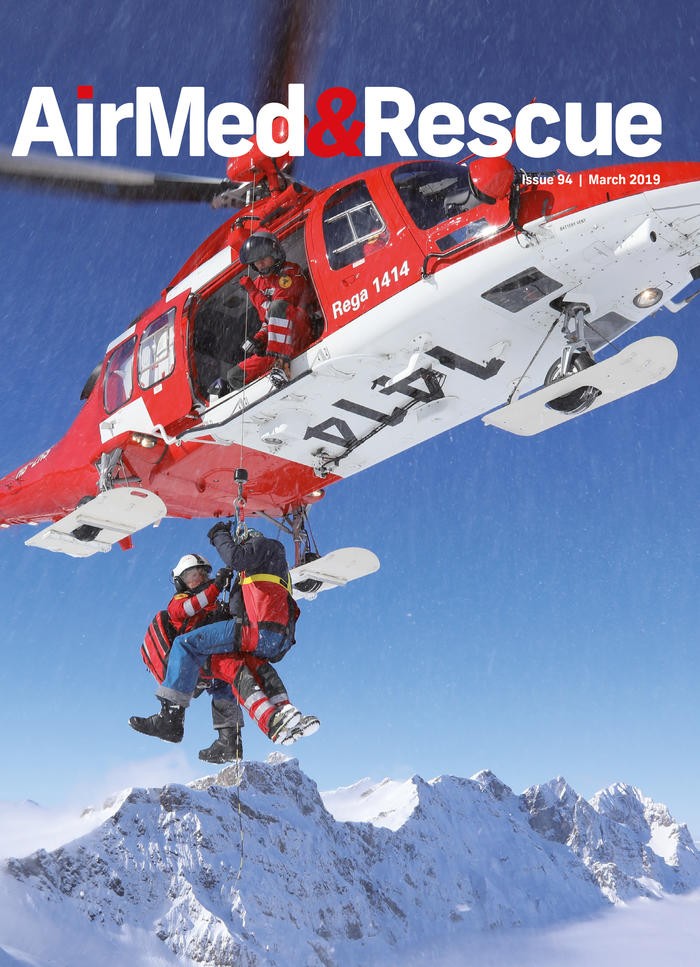

For those conducting aircraft operations, the survival vest is an excellent and comfortable way to carry survival equipment. They are extensively used by military and civilian aircrews (usually engaged in SAR/remote work). Vest types can range from complete, whole body vests with built in life preservers as pictured, to smaller purpose-built platforms such as the Switlik constant wear aviator vest and similar vests with modifiable pouches for custom fit.

I utilise the Tac-Air G2 vest that has the integrated hoisting harness. You can get it without this at a more affordable price. What I really like about this vest is that essential survival gear is housed within removable ‘trays’ that slide in each side of the vest. This leaves the MOLLE platform free for you to customise.

Build your own

It is easier to build a generic kit that applies to most world conditions, and then expand your individual knowledge on how to survive more effectively using your kit in the climatic region you are working in. Remember: knowledge weighs nothing. For example, here in Guatemala, it is perfectly feasible to survive for an extended period of time in the jungle with nothing more than a machete (and I mean three weeks or more). A machete can build shelter, produce fire-making devices, access drinking water from plants, and prepare traps and snares for food. You just need the knowledge on what to use it for.

Once you have your kit – practise! It doesn’t need to be a full paid course. For example, take your firelighter (whatever the weather) and walk into a grassy area. Then, with a limit of 100 meters, gather what you need to make and start a fire. Rain, shine, or snow – practise!

March 2019

Issue

In this issue:

Traumatic brain injury transports - best practice

Survival of the fittest - ALSE - Staying alive after a helicopter crash

Surf's up - Surf-based rescue techniques

Never forget - the lone survivor of a helicopter accident

Patient safety is the number 1 priority for ER24

Interview: Mikko Dahlman, Coptersafety

Provider Profile: LifeFlight Network

Company Profile: Sikorsky / Lockheed Martin

Case Study: AirLec Ambulance describes the challenges of an evacuation from a warzone

Chris Sharpe

Chris Sharpe is a contributor for the education company Heavy Lies the Helmet. His experience includes Project Manager, Chief Aircrewman, and Flight Paramedic for HeliSOS HEMS/Rescue Helicopter in Guatemala, and the Chief Aircrewman at Black Wolf Helicopters. Sharpe has been flying for over 28 years; having over 15,000 flying hours and 6,000 rescue operations to his credit. He is a safety and survival expert, teaching survival techniques to both civilian and military helicopter crews in Guatemala. He is also the recipient of the HAI 2019 Salute to Excellence Safety Award.