Retired pilot Byron Edgington on the joy of flying single pilot

Byron Edgington, a retired military and commercial helicopter pilot, shares an excerpt from his book, PostFlight: An Old Pilot’s Logbook, in which he addresses the benefits and perils of choosing rotary-wing over fixed-wing aircraft

I had the opportunity to fly for the airlines many years ago, but I decided to stay with helicopters, and I’m glad I did. Rotary-wing aviation was a perfect fit for me, and I’ll never regret it. For one thing, virtually all commercial flying in helicopters is single pilot.

Why I love flying single pilot

I enjoyed flying single pilot because I was the one making the decisions. It was all on me whether to accept a mission or not. All on me to fly the machine, to interpret the weather, to manipulate the controls, and to manage the aircraft systems and fuel etc. When something went wrong, it was my responsibility to deal with it correctly. It was on me to take the machine into the sky, keep my passengers and the aircraft’s owners happy, and to bring it all back at the end of the day in one chunk. I liked that sense of agency.

Helicopters typically have more moving parts than airplanes, thus there’s more to preflight, (some say more to go wrong). Helicopter operators, by and large, work within a smaller profit margin, so a helicopter malfunction can be a bigger potential problem for your boss, thus the pressure on you to fly a marginal machine could be higher as well.

As for engine malfunctions, helicopters have the advantage of a maneuver called autorotation, which allows a gentle, controlled landing in the event of a failure. So if things get eerily quiet, and your fuel consumption drops to zero, as a helicopter pilot you’ll have better options than a fixed-wing pilot on where to put the machine down.

The negative aspects of commercial helicopter operations aren’t numerous, nor onerous, but they are noteworthy. For one thing, as a rotary-wing pilot you’ll commonly work at the end of the road, especially when you’re a rookie. The upside to taking such jobs is that they often provide you more real-world experience than others do, for richer, more memorable flying.

Another advantage to jobs in the bush is that you’ll often be the pilot. That is, when you arrive at the job site, there’s no need to look for a fellow pilot, because there ain’t one. You’re it. Being the sole operator of a helicopter day in and out gives you the opportunity to really know the machine’s flight characteristics, its quirks, and its limitations. It also demands from you a thorough understanding of the maintenance aspects of flying the machine, and keeping it Federal Aviation Administration legal.

Never the same flight twice

Helicopter jobs can be mundane, crude, and often remote. However, that aspect of it could be a plus for you. If your preference is for remote, out-of-the-way places, and exotic, arcane flying missions, there are likely more of those positions on the rotary-wing side of aviation. My air medical flying experience was an example. For 20 years, I flew a medical helicopter for a hospital, which was far and away the best flying job I ever had, and even after all that time, I can say with confidence that I never experienced two duty shifts that were the same. Beyond that, with the exception of a power pole counting job, and a few times flying news and traffic when I could have phoned the information in, I never had a boring day of flying.

In much of the helicopter community in days gone by, if you flew in remote areas, for example, forget crew rest regulations. They were lax at best, and pretty much unenforceable in the bush.

Sublime power of vertical lift

I couldn’t imagine a better, more fulfilling life in the sky for myself than being at the controls of a helicopter. There’s something sublime about hovering. Raising the collective, feeling the helicopter rouse itself, then defy gravity and leave the ground, is superbly gratifying.

Regardless of which helicopter I flew – the two-seat Hughes 269, the Bell UH-1 Huey, the AS-350 AStar, on up to the 50,000-pound gross weight Boeing CH-47 – the thrill of hovering never diminished. Holding 7,000 horsepower in my left hand on the thrust lever when flying a Chinook was an amazing feeling, and an awesome responsibility.

Yet another reason for you to fly helicopters is the sheer thrill of it. Flying an airplane can reward you in many ways. It can offer you a degree of maneuverability, and the visceral thrill of being airborne, but nothing provides you thrills like flying a helicopter does.

Another personal consideration is the vanity of being able to fly a helicopter, something very few people can do.

July 2021

Issue

- Adapting skills and aircraft for police multi-mission capabilities

- How UAVs can boost force efficiency

- Selecting the right equipment for police surveillance and SAR

- Interdisciplinary HEMS crew integration in Norway

- An exclusive excerpt from PostFlight: An Old Pilot’s Logbook

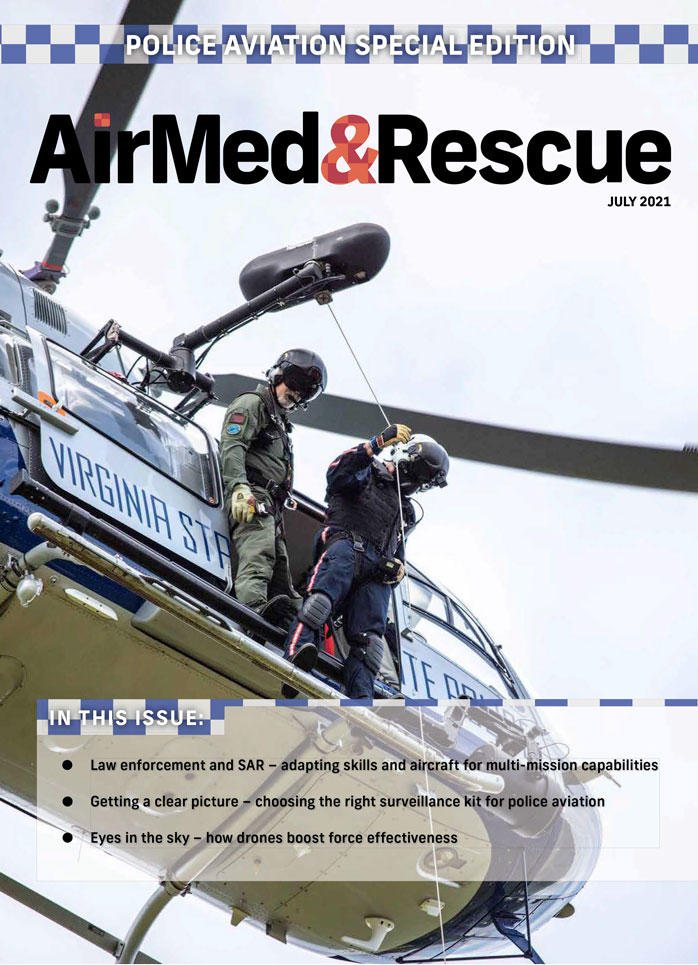

- Interviews: Tab Burnett, Alaska Department of Public Safety; Kevin Kissner, Virginia State Police

- Provider Profile: European Air Ambulance

Byron Edgington

Byron Edgington is a retired military & commercial helicopter pilot. A Vietnam veteran Huey pilot, he flew all over the world, in 25 different aircraft types, including 20 years in Air Medical in Iowa, where he flew 3,200 patient missions. In 52 years in the cockpit, Edgington logged 12,500 hours of flight time. He is the author of four books, and numerous aviation essays. His latest book is PostFlight: An Old Pilot’s Logbook, Tips for Pilots, and for Those Who Wish to Be. The book is aimed at young people, especially young women, who dream of a flying career.