Provider Profile: Dauntless Air

Oliver Cuenca talks to Jesse Weaver, Dauntless Air Director of Operations and Chief Pilot, about fighting fires and maintaining high standards of safety

Dauntless Air is an aerial firefighting provider that delivers flexible services on a contractual basis – rather than being tied to a specific area, aircraft and pilots are relocated according to need. As a company operating across the entire US, Dauntless has to adapt to regional differences as required.

“Geographically, from the Midwest to Alaska, to the Western States and Southern States, you’ve got a lot of different terrain and fire types,” said Jesse Weaver, Dauntless Air Director of Operations and Chief Pilot. “Some areas are more mountainous, so they definitely see the value of small, highly maneuverable planes. Others, like Florida, have a lot of retardant exclusion zones because of all the wetlands, so scoopers work well in those places.”

Additionally, political dynamics can impact government contracting: “Some areas are more adept at using scoopers and deploy them aggressively – whether in rapid initial attack roles or as part of an extended attack. They’ll also launch us if they get requests from cooperating agencies,” Weaver said. “However, some locations aren’t as quick to send us out because they don’t want to risk the resource being unavailable in the event of an initial attack need. On the other hand, some states are reluctant to use scooping aircraft at all, even though they have lots of water sources.”

Dauntless is one of the leading US operators of the Air Tractor AT-802F Fire Boss amphibious water tanker – with a fleet of 15 of these fixed-wing aircraft. It was supported by a team of 27 pilots and around 20 ground crew members during the 2022 wildfire season.

“There are a variety of operational and financial benefits that come with employing a Fire Boss, compared to a larger scooper or helicopters,” said Weaver. “For the operating cost of a single CL-215T or CL-415, you could contract eight to 10 Fire Bosses.” He added that while ‘one 215T or 415 is going to do an excellent job, it can only be in one place at one time’.

“Tactically, you can spread out the eight or more Fire Bosses over your district, increasing coverage area and giving you the ability to fight several fires at the same time,” he added.

The Dauntless Fire Boss fleet is versatile in its own right, with the aircraft modified ‘with technology that doesn’t come as standard’ to suit the company’s specific needs

Additionally, Weaver added that the Dauntless preference for smaller aircraft is also guided by the locations – remote, rural and often sparsely populated. Compared with a larger aircraft, such as the Canadair CL-215 or CL-415, the Fire Boss is ‘smaller, simple and tough, and doesn’t need to be close to a major airport or maintenance facility’. He added that: “It requires less space on a ramp, less fuel in a day, and fewer crew to support it, which means fewer people taking up the available hotels or living space. It can go live in the weeds for long periods with very little support.”

Weaver added that the Dauntless Fire Boss fleet is versatile in its own right, with the aircraft modified ‘with technology that doesn’t come as standard’ to suit the company’s specific needs. “We’ve got heads-up displays (HUDs) to improve safety and reduce pilot fatigue,” he explained. “We also have infrared imaging to help pilots safely maneuver through thick smoke and trees, and to reliably hit important targets like the fire’s edge and hotspots. Height above surface alert systems (HASAS) are also installed, to enhance safety for pilots working off glassy or smooth water, where it’s difficult to determine the plane’s distance from the surface.”

Other modifications include gel mixing systems that inject environmentally safe water enhancers into each load – making the water less likely to evaporate before landing – and the Electronics International MVP-50 engine monitoring systems that ‘simplifies instruments and records engine mechanics’.

“A final thing I’ll highlight are the smokers we have on all planes,” explained Weaver. “These are smoke generating systems that allow our pilots to make themselves visible when needed, which is really important if there’s an unidentified aircraft in the fire traffic area. We also use smokers to check wind drift, but they’re primarily to identify ourselves and communicate without having to use the radio.”

As a US-based operator, Dauntless Air works through the ‘Interagency system’, that ‘consists of federal and state agencies that each contribute resources or funds into a more or less shared pool of US firefighting assets’. This resource-sharing system allows operators to provide support to other government agencies with minimal bureaucratic mess.

“At Dauntless, we have at least 18 different federal and state contracts that we can work on through this system. Some of them are on-call, or call-when-needed, and the others are exclusive use, but they’re all in Interagency.”

Weaver added that it was a requirement for all operators within the system to have their aircraft and pilots ‘federally carded’. “Operators have to meet a certain standard, so the cooperation starts right there,” he said.

We have at least 18 different federal and state contracts that we can work on

Weaver explained that the US aerial firefighting community is ‘relatively small’ and tight-knit, ‘particularly for scoopers and Fire Bosses’. “Most everyone knows each other,” he explained. “I have good personal relationships with other managers and owners, and we cooperate quite frequently on how we can integrate our different companies into an effective firefighting tool.” He added that this community spirit was in part a product of the job, driven by the need for ‘safety and efficiency’.

“At the end of the day, when we’re on a fire, it doesn’t matter who we work for. Fire is the mission, and it’s in everyone’s best interest to work together and get the job done.”

Aerial firefighting missions are a dangerous business, so regular, rigorous training is a priority for Dauntless. “We take a lot of pride in our annual training program, which spans two weeks,” Weaver said. “We cover the contractually required classroom training, but decided years ago that we needed to expand that classroom portion and add a significant number of training and proficiency live-flying scenarios.”

He added that while the company has found in the past that flight simulators can be ‘helpful’, ‘nothing quite compares to actual flight time’.

Over the course of these two weeks, there are ‘upwards of 140 sorties’, while Dauntless pilots spend between 120 and 140 hours in the air. During the same period, mechanics are on-site to practice maintaining the aircraft and to take additional maintenance-related classes, while crew chiefs simulate dispatches and loading aircraft ‘as if it’s fire season’.

“It gives everyone a chance to work on their technical skills and ability to collaborate and work as a team,” Weaver explained.

This rigor extends even further when training rookies. “Across the industry, new Fire Boss pilots typically fly only seven to 10 hours before the wildfire season starts,” said Weaver. “However, we’ve found that it’s really difficult to evaluate and train up a new pilot in that standard period of flight time, so we’ve doubled that.”

New Fire Boss pilots at Dauntless Air fly between 20 and 30 hours in the pre-season, including both solo hours and flights with an experienced pilot in a two-seat Fire Boss.

“I can’t overemphasize enough the training value that you get from a two-seat Fire Boss,” said Weaver. “When I did my new pilot training around two decades ago, two-seaters didn’t exist. Instead, like all Fire Boss pilots at the time, I was trained over the radio by someone sitting in a boat below me.

“Naturally, there are limitations to that approach, and it caused me to pick up a few bad habits that took several seasons to unlearn. There’s no reason for a new pilot to go through that today,” he added.

Another key aspect of annual training is multi-crew exercises. In 2021 and 2022, this included bringing in an Air Attack platform to fly above the target training area, alongside a total of 75 Dauntless crew members, 31 Texas Forest Service incident commanders (IC) and various stakeholders from the US Office of Aviation Services and Bureau of Land Management. “While one group of pilots worked with the Air Attack platform … another group worked with ICs on the ground, giving both Dauntless and the ICs practice in calling in aircraft and performing rapid initial attacks on a simulated fire drop zone,” Weaver explained.

Other things touched on in annual training include:

- CPR

- Human factors: leadership and effective team building

- Water reading, natural navigation

- Tanker base etiquette and model behaviors training

- Appropriate assistance to

- downed aircraft

- Tips for mental health management

- Formation flying and rough water scooping.

“Separately, we also send our people to the Marine Survival Training Center in Lafayette, Louisiana,” he continued. “As part of that program, our pilots practice underwater egress in a simulator. They also learn how to use an aqualung if they get stuck. There’s a big focus on self-rescue and how to survive long periods of time in the water.”

While training is important, foundations at Dauntless are built on its ability to find and hire the right people. “Beyond prior work experience, there are specific traits that we look for,” said Weaver. “You must have a team-first mindset. What we do is impossible without teamwork. You’ve got dispatchers, pilots and ground crews all relying on you to be part of a unit.”

Another key trait is ‘willingness to learn’. “You’ve got to be open to learning from others. That’s why we like folks with diverse backgrounds, so everyone can bring different piloting experience to the table and learn from each other.

The best teams are full of friendly, sociable people who socialize outside the job

“Sociability is another trait we look for,” he added. “Fighting fires can be a really lonely job. You’re usually far from home and gone for months at a time, so we’ve noticed that the best teams are full of friendly, sociable people who socialize outside the job.”

In terms of previous work experience, Weaver looks for an agricultural pilot with ‘some kind of other experience as well, such as in the military or corporate spheres’.

“Agricultural pilots are used to a single-engine environment, low-level flying and a variety of terrain. That translates well to aerial firefighting. Also, it’s common in ag flying to pilot smaller stick and rudder, or tailwheel planes without automation – which is really helpful experience, because there’s no automation or autopilot in aerial firefighting.”

He added that ‘the best ag pilots know what it’s like to jump into an airplane at the crack of dawn and … maintain a grueling pace without sacrificing diligence’.

Weaver added that military pilots also ‘have a lot of transferrable skills’ – most notably, ‘they know how to be at their best in high-intensity situations … communicate effectively and know how to work together as a team’.

When talking about safety, Weaver mentioned that the growing popularity of civilian drones ‘definitely complicates things’. “Whenever one is spotted [in an active firefighting zone], that often means all aerial resources have to go away until law enforcement can show up and make sure the drone is on the ground,” he explained, adding that ‘a pause in aerial support can make all the difference for fire containment – so it’s a very big deal’.

Despite this, he said that ‘we don’t actually encounter civilian drones too often’. Instead, a bigger issue is the presence of aircraft ‘that aren’t supposed to be in the fire traffic area’. “More often than drones, we’ll have general aviation or military aircraft flying through our areas,” he said. “Fortunately, those aircraft are manned and are bigger, so they’re easy for us to see … and clear out.”

January 2023

Issue

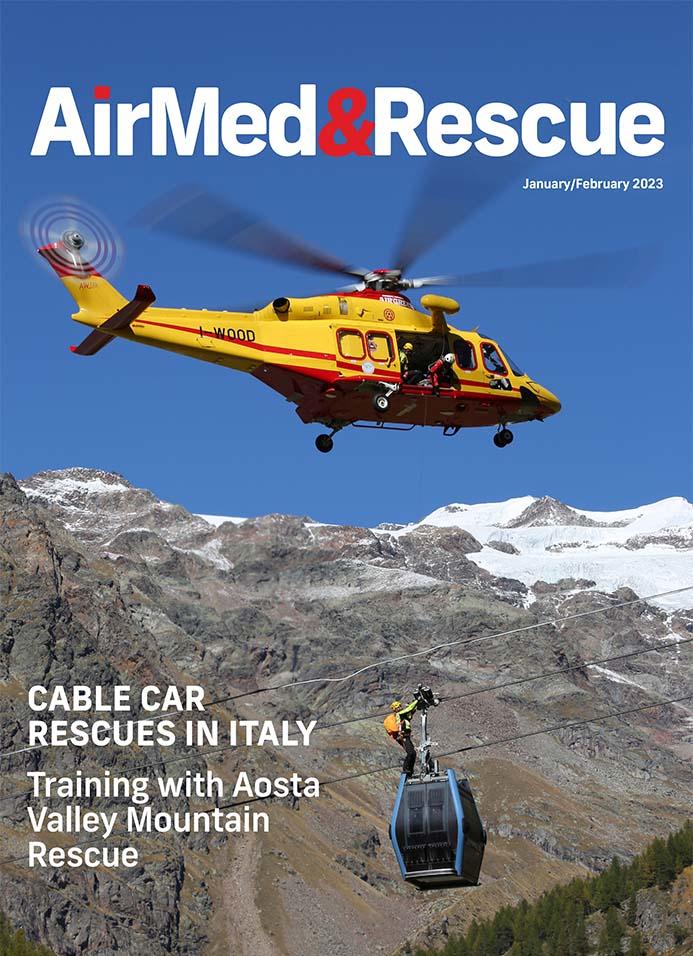

In the January/February 2023 issue

Technology to aid, enhance and support you in the cockpit; how do HEMS operators around the world approach SAR with different rules and technology; what do people know about AA: who can access it, when can they use it, how much does it cost, and how is it funded; plus a whole lot more to keep you informed and good to go!

Oliver Cuenca

Oliver Cuenca is a Junior Editor at AirMed&Rescue. He was previously a News and Features Journalist for the rail magazine IRJ until 2021, and studied MA Magazine Journalism at Cardiff University. His favourite helicopter is the AW169 – the workhorse of the UK air ambulance sector!