Interview: Sean Bryan – REVA’s Director of Medical Operations – Western Hemisphere

Knowing the demands of flight nursing inside and out, Sean Bryan, REVA’s Director of Medical Operations – Western Hemisphere, explains to Jon Adams why fixed-wing healthcare is so important to him and the patients he cares for

What made you interested in pursuing a career in nursing?

I was born and raised in the northeast part of the country, up in the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh area. I initially wanted to pursue a medical path in the military because my father was a Navy Corpsman, providing direct medical support to the Navy and United States Marine Corps. But my mom politely told me, ‘No, you’re not going to do that lifestyle again’. So I ended up going to university for nursing. Initially, I wasn’t really feeling it much as you don’t typically get to do critical care / emergency medicine in the first year of the program – it’s a slower pace – a little floor nursing, learning the basics and fundamentals, which is fine, but not for me. I was going to hang it up and then, unfortunately, I was losing my grandmother to lung cancer. When she passed away, I had a self-evaluation and decided to give nursing a try again and became a Registered Nurse. I didn’t really know if nursing was for me, but after I experienced how the work of nurses impacted my life and my family’s life, I changed my mind.

You mentioned the desire to follow your father into combat medicine – is the pace of it what got you interested working in intensive care and emergency rooms?

I was pretty stubborn going through nursing school. When I got to the critical care portion – emergency, trauma, and intensive care unit (ICU) education – I was dead set that this was what I was going to do as soon as I passed my board examinations. In 2012, it was difficult for a new graduate nurse to get into an emergency setting straight away. I was very lucky to be given an opportunity with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center straight out of school, working in the emergency room (ER) in McKeesport, Pennsylvania; I had friends who already worked there that were able to vouch for me. My desire for a fast pace, excitement, and something different every day –a controlled chaos – got me into the ER early.

With the pace, your focus and your desire to be in that arena, what made you change discipline to become a flight nurse?

When I graduated, I had multiple goals in place: the first was to get a job in emergency medicine, which I was able to do; the next goal was to get my time in to become a flight nurse. We had a family friend who was a medevac pilot for STAT MedEvac. I was able to shadow them for a day or so, and once you get a taste of the flight industry, it’s kind of a bug. Also, flight medicine is really one of the most demanding jobs in emergency and critical care medicine – there’s literally no day that’s the same, making it very rewarding. You’re truly helping people who are in a very desperate situation and really need you. I was able to achieve my second goal after three years on the dot – due to accreditation standards, you have to have a minimum of three years of ER/ICU experience to get into flight nursing.

You’re truly helping people who are in a very desperate situation and really need you

As you say, every day is different and you’re helping people that desperately need it; what sets flight nursing apart from standard emergency medicine and is it what you expected?

When I first got hired as a flight nurse, I wasn’t 100 per cent ready. It was just something I was very aggressively and persistently pursuing. I kept knocking down the door at REVA until I had my three years in the ER. At REVA, we do a lot of high-acuity critical care transports and we help people in dire need; well, we do that every day in the ER/ICU as well, but the main difference is that, in the air, there’s much more autonomy – it’s just you and your partner (or maybe an additional partner or a physician). There’s very little support up there, and you are expected to be able to operate at a very high level at all times, to be able to maintain your composure and have a solution for whatever may arise, or understand where to find an answer. Early on, I had to learn a couple of lessons the hard way – the most important thing is that you do learn from those opportunities.

Is there a typical day for a flight nurse, doing repatriations, internal transfers, air ambulance, medevacs etc?

Our days range a little bit differently in the fixed-wing world. I have a number of nurses on call – the full-time nurses do eight days on and seven days off, that’s eight straight 24 hour shifts. When they get called in, they’ll be wheels up and execute the mission, then afterwards they get minimum of 10 hours of rest before they can be called again. We have four main bases: Florida, Puerto Rico, New York and Ireland. REVA does a little bit of everything, from repatriation to commercial medical escorts, and also domestic interfacility transports – anything that you could think of, REVA is able to offer. For instance, we just did a transport where I flew with a patient – critically vented with external ventricular drains in place – from Vietnam to Nashville, Tennessee. Expanding into Europe has really helped with our global reach. Largely due to our main hub here in Fort Lauderdale, we complete many critical care transfers in and out of the Bahamas, Caribbean and Latin America every day, primarily back to South Florida or elsewhere in the USA. During the cruise industry peak season in the area, we receive calls more frequently. On average we complete roughly four international to domestic patient transports a day and we anticipate the transport volume to continue to increase.

During the pandemic, we converted a 737 into a flying hospital to fly 25+ Covid-positive patients from Uruguay to Miami. We also converted a 787 and flew roughly 50 chronically-ill children and their families from Philadelphia to Abu Dhabi. Those are a couple of examples of what we do besides our core air ambulance business.

Over the past year, I was fortunate to play a large role in developing a program with Tropic Ocean Airways, we are now executing medevac missions on Cessna 208B seaplanes, allowing us to fly in and out of the Bahamas, landing on the water roughly every other day of the week and getting people out of isolated islands.

You mentioned that you’ve got a lot of autonomy and not a lot of support; do you find that you need special equipment to help you to provide a level of care that is required for critically-ill patients?

REVA does an amazing job in making sure that all of our staff have the appropriate tools to be successful at any time. We carry X Series Zoll cardiac monitors and Hamilton-T1 ventilators, we also have backup Zoll ventilators in the event that there is something wrong with the primary. In addition to that, we carry multiple IV pumps; a portable ultrasound, giving us ultrasound in the air; an i-STAT device that we can use to draw labs at any time; and we have the capability to carry blood – we have it available 24/7/365.

In addition to the physical tools, we focus heavily on training. We do our training towards accreditation standards, and we also do iterative training through quality assurance and quality improvement.

We do our training towards accreditation standards, and we also do iterative training through quality assurance and quality improvement

We’ll train quarterly on hot topics, such as cardio issues, neurological issues, advanced airway courses etc – whatever the staff feel that we’re seeing often and we could use a little bit more education on. We also make sure to have our protocols available to our staff at all times. International cell phones are given to staff for each flight so they’re reachable in every country that we go to, allowing us to call when we get to the bedside with a report; for extreme cases, we carry satellite phones.

In terms of really ensuring that what we’re doing is safe, we have four medical managers on call 24/7 in addition to our Medical Director, Dr David Farcy. When a flight is going, there’s a medical management team member on call that day, and they’re very involved with the planning and execution of each mission. If there is a critical care patient that day, that resource manager is involved early on, making sure the mission is staffed appropriately and making decisions on if it needs to be escalated to our medical director for additional assistance. We also have a medical coordinator back at base, on call and ready to assist.

What comprises the teams that operate in the air and how are they organized?

Our primary team is a nurse and paramedic. Our second most common team is nurse and critical care paramedic (CCP). We also have nurse and respiratory therapist team. To any one of those combinations, we’re able to add a physician, depending on the patient acuity, or maybe at the client or family member request. The CCP is a very common role for us – they’re signed off to run a ventilator, managing airways efficiently and appropriately, and they’re very utilized, bringing such a tremendous skillset to our team.

As a Director of Medical Operations, do you still maintain active flight status?

I flew nine missions in March in addition to my Monday–Friday job. As a director and as a leader in the company, you need maintain that skillset and fly! Showing your team that you understand the job – the stressors and challenges – and that you can still do it goes a long way. It’s leading by example. I do absolutely maintain an active flight status and I enjoy it – it’s nice to go back to doing what was my early goal, becoming a flight nurse.

What are the most challenging types of flights and how do you prepare?

We’re fairly lucky in the fixed-wing world in that we’re typically not going in blind anywhere. A really a nice part of the industry is that whenever we get a request through our operations center, we’ll have some basic medical information on the patient. Our 24/7 medical coordinator – also a flight nurse or flight paramedic – will get this request and directly call the hospital for an intake report. We’ll be able to speak with the treating physician or nurse in whatever destination we’re going to go pick up; that allows us to have a good general idea of what is going on, such as if the patient’s ventilated, critically ill, on vasopressors etc. We get this basic info so we can prepare on the way, if we know what medications the patient is on, we’ll have our staff premixing the intravenous (IV) drips on the flight down, so that when we get to the hospital, it’s a relatively quicker turnround. It’s just about communication and being prepared.

What advances in training or technology have you seen that have made the most significant difference in flight nursing, and what changes do you foresee coming in future?

Some of the biggest improvements that have made our jobs easier at REVA have been the advancements in cardiac monitors, monitoring capabilities and ventilators. The change to the Hamilton T1 ventilator was just tremendous, especially post-pandemic with some of the very complex pulmonary cases that we’ve encountered. The Hamilton T1 ventilator is essentially a hospital ventilator that is a transport size, it’s very compact – almost everything you can do in the hospital, you can do with this ventilator. Also the i-STAT, being able to draw labs anywhere: you can be 40,000ft in the air or in another country and have access to this readily available resource that’s very beneficial with a critical patient.

What is the one thing that people should know about flight nursing that doesn’t get enough coverage?

As I was going through nursing school and early in my career, I didn’t hear much talk about fixed-wing flight nursing, it was all very heavily rotor based. When considering flight nursing, everybody immediately thinks of helicopters. Continued education on that aspect of flight nursing and the critical care transport world is something that needs to be blasted out there because there’s a significant need. Prior to the pandemic, we were doing roughly 1,500–1,600 transports a year. That’s a lot of patients. And, in a jet, those are mostly eight to 14 hours per flight. When I was speaking in a conference to emergency and critical care nurses on fixed-wing nursing, nurses came and told me that they didn’t even know this existed. For most patients that we transport, their families and loved ones also had no idea it existed until the moment they needed it.

You spoke about the novel work that you and REVA are doing with seaplanes, can you expand on that?

No one else is doing this. Over the last year, we formed an alliance with Tropic Ocean Airways who own the largest amphibious aircraft fleet in the world, based out of Fort Lauderdale. We’ve been trying to solve a problem for years: how to evacuate people off private islands and hard to reach areas. The solution was to outfit 14 Tropic Ocean aircraft, Cessna 208Bs, and put everything that we use in our jets into these aircraft. Now, we are able to literally land anywhere – we’re landing on the ocean and picking people up that do not have medical access aside from basic clinics.

We’re landing on the ocean and picking people up that do not have medical access aside from basic clinics

We’ve picked people up off the beach and done middle of the ocean boat and jet-ski dock transfers. In the last couple months, we’ve done 27 of these emergency calls with seaplanes. We would have actually executed probably another 15 more of those missions if not for the global pilot shortage and other limitations, such as being a daylight operation because of the water. This expansion is one of the things I’m most proud of being a part of, and it’s just continuing to grow. The team loves it, it’s like a mix between rotor- and fixed-wing work because we’re going to a unique scene – a beach or the ocean – rather than simply landing at an airport or going to a hospital.

June 2023

Issue

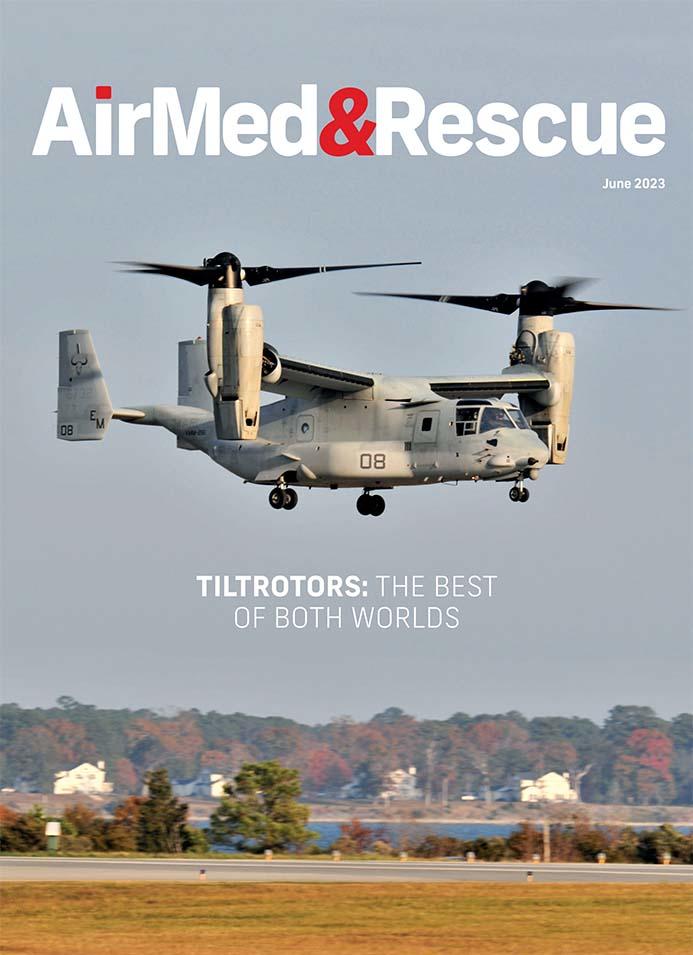

We find out about attracting the best staff; what is being done to improve sustainability; how tiltrotors compare with conventional aircraft; how rescue services approach sudden and extreme flooding; and the challenges facing MRO supply chains; plus all of our regular content.

Jon Adams

Jon is the Senior Editor of AirMed&Rescue. He was previously Editor for Clinical Medicine and Future Healthcare Journal at the Royal College of Physicians before coming to AirMed&Rescue in November 2022. His favorite helicopter is the Army Air Corps Lynx that he saw his father fly while growing up on Army bases.