Interview: Markus Lapitsky, Chief Pilot for the Aviation Unit in the Gwinnett Police Department, Georgia, USA

Policing the skies of Gwinnett County: Markus Lapitsky talks to Jon Adams about the increasingly diverse role of the police aviators of Gwinnett County

How did you get interested in aviation and why specifically in policing?

I grew up in New York and, since I was a young boy, the New York State Police appealed to me – they were smart and squared away. Also, the lights and sirens, of course, it didn’t matter what vehicle it was, I was out there watching. But I’m also a firm believer that policing is a calling. The ability to lock up bad guys, and to help people and solve their problems was what guided me. I felt it was my duty to serve. Once I got into the Police Department in Georgia, I worked in a couple specialized units and had some interactions with our aviation unit – one of the pilots in the aviation unit was in the police academy with me and that helped me to develop the bug to get into the aviation. He would call on me to be a tactical flight officer (TFO) – essentially the second officer in the aircraft who works all the police equipment and the radios. I started doing that on my own time but, inevitably, I wanted to sit in the pilot’s seat.

What aircraft do you and the department operate?

We have two McDonnell Douglas 530Fs – known as ‘Little Birds’. We’re fully trained on those and as the only aircraft that we operate at the moment, we’re specialists in it.

Wwhat are the different responsibilities of the TFO and the pilot?

I like to call the pilot, essentially, an Uber driver. The TFO, however, is the most important position, arguably not only in the aviation unit but within the whole department. The ability to multitask and operate under high stress situations is paramount for that position. This means that the TFO is essentially the officer who runs the mission or the call for service. They work the radios, talk to the pilot so that the aircraft can be positioned over the scene of a call or a target location, use a camera spotlight, and are another set of eyes for the pilot. They also have a minimum amount of flight hours – should the pilot become incapacitated or have some kind of an emergency, then they would be able to take control and land the aircraft safely. They’re the quarterback of the operation.

The TFO, however, is the most important position, arguably not only in the aviation unit but within the whole department

What kind of missions do you tend to fly? Are there any particular types of missions that are more challenging than others?

Every mission serves its own challenges. For our department here in Gwinnett, pretty much what we’re used for is to support our ground units and the department. We do a lot of missing persons, whether it’s someone with Alzheimer’s or a child that didn’t say he was going to his friend’s house. We also work hand-in-hand with our canine unit – anytime they get deployed and go into the wood line or start to track a subject, we’re up above, giving out locations and trying to scan ahead to see if we can divert them, or protect them from an ambush.

We’re lucky enough to do some patrol flights during our shift, just like an officer driving on the streets through a neighborhood, we’re out there watching high-crime areas – like the malls – for entering automobiles and parks for suspicious persons, and backing up officers on traffic stops. We’ll listen to the police radio, if there’s a call that we think that we would be good and utilized as a resource, then we’ll head that way. We have a quite a bit of autonomy when it comes to going on missions.

Do you have any particular hazards that you encounter with police operations that wouldn’t necessarily be experienced by non-special missions?

We actually had almost a dozen laser strikes in 2022. Thanks to our advanced camera that we have on the side of the aircraft, we had four to six arrests for those laser strikes, and a couple of them were even newsworthy. We also have other hazards because of the job that we do, for example, if there’s an officer down or gets hurt or injured or shot, that pressure may be a little bit different than typical.

What kind of enhanced equipment do you have on the aircraft that helps you with your work?

We have a TDFM-9000 Technisonic radio onboard. The TFO can use it to listen to up to six channels. For example, here in the Atlanta area, we can not only monitor all of the precincts within our department, but we have our neighboring precincts’ channels, State Patrol’s channels, Atlanta PD’s channels, fire channels and any other channel that we may need to talk to anybody on, and who we would be able to assist. Being able to talk on all the channels allows us to navigate and communicate with anybody at any time. It’s an abundant amount of talking and listening, but it’s such a quick and easy button press to switch between them, and it operates so much better than the two separate radios that we had in the past: one was an ‘old school’ car radio and the other was one of our portable radios.

Being able to talk on all the channels allows us to navigate and communicate with anybody at any time

Another piece of equipment is our SHOTOVER mapping system (formerly known as Churchill Navigation), which is an augmented reality system (ARS). It gives the TFO the ability to punch in an address and then it’ll tell the pilot where to go and how long it takes to get there. It will also sync with the camera and point it directly at that address. There are times where we’ve been close to an emergency call and as soon as the TFO punches in the address, the camera is already on target giving a high probability of capturing whatever is happening. The mapping system also provides an overlay of our clear camera. For example, if we were watching a subject run, we would be able to give out the exact address; also if they’re behind two units on the ground, we can set up perimeters because we can zoom out and get the neighboring streets. It’s also got the ability to do speed verifications with motorists. Additionally, we can both record and take still pictures, and it has the ability to replay the recording in situ. For instance, if we have three suspects run from a vehicle in different directions and we stay with subject one, while still in the air, we can just stop the video, replay the recording and disseminate the information about what subjects two and three are wearing and which direction they departed. There’s no time gap or delay. In the past, we would have to download that video, come back to the hangar, shut down, watch the video and only then be able to give out that information.

How do you navigate and manage the priorities and responsibilities for crossover between neighboring authorities when there’s an incident on the border between those two areas?

Our radio dispatcher has a point scale system based off the call on how it’s ranked as a priority. We also know through our training and experience which call we would be more useful for. We have policies that state what we can and cannot do for external agencies, including plans for who goes first and when we’re able to respond. Regarding the agencies within the county, we have a lot of support from our upper management. We’re police officers and we’re here to serve, so if they need help or assistance, it’s no problem for us to go and help out.

We’re police officers and we’re here to serve, so if they need help or assistance, it’s no problem for us to go and help out

What’s the weather like in Gwinnett County and do you manage to fly most days?

Generally, the weather is amenable to flight operations. We are visual flight rules (VFR) only, so we have to be able to see, and abide by the rules and regulations set in place by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). But the weather in Georgia this year has been pretty awkward. In certain months, like February, we get a lot of fog and some rain, and then in the summer months, we get these pop up thunderstorms. We do fly both day and night – using night vision goggles at night – and if we fly in rain, as long as I can see through it, we’re good to go. We are a support unit, so if weather prevents us from flying, there’s no reason for us to go in the air and take risks.

When you’re not flying, is that time spent mostly training for operations or do you do other police work?

We are still primarily police officers. There are requirements set by the State of Georgia that officers need to meet a minimum amount of hours of training every year. So, if the weather is bad, or an aircraft is down for maintenance, we try and schedule our training on those days; such as qualifying with our firearms (‘in service training’). We also do other training to get certifications – intermediate or advanced – for me, it’s developing into a leader/manager. We’ve also got instructor classes to help you be a better teacher and mentor, and other classes like that.

We are all also part 107 certified to operate drones. If the aircraft is down and the weather is still good enough to deploy a drone, we go out in a patrol vehicle and respond to calls with the drones

There’s a lot of administrative duties in the aviation unit; we have to keep up with flight hours, monthly reports, fuel logs and everything else. We train with the aircraft manuals as well, going over emergency procedures. We have a flight simulator here, so we can practice procedures on it and work on some instrument flight rules training. We do our inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions (IIMC) training on it. For the FAA, we’re allowed to log up to 21 hours of instrument time with it. The two newer officers here swear that they learned to hover sooner than from a real aircraft by just playing with the simulator. It allows you to create muscle memory and is safer to operate all our emergency procedures on the simulator.

We are all also part 107 certified to operate drones. If the aircraft is down and the weather is still good enough to deploy a drone, we go out in a patrol vehicle and respond to calls with the drones, backing up officers that way. There is, of course, another door of training there. So we’re constantly staying up to par with the rules and regulations, as well as making sure we’re keeping up with our flight hours for the drones. We’re very busy even if the aircraft’s not in the air, that’s for sure.

Do you train with other agencies on different types of aerial policing across the mix of rural and urban landscapes?

We go over to Atlanta PD to assist them and they train us on how winds come over their buildings. Their blocks are a lot shorter than ours but we do have a couple of major interstates that run through our county. We also train with our State Patrol agencies for marijuana detection. But for the most part, the only challenging thing is going from one environment to the other. For instance, you set up your camera to suit the needs of a well-lit area and when you move into the darkness of the night, you’ve got to then readjust the settings. The mentality of the TFO has to be able to understand and adapt to it.

As pilots, we’re always learning. Every day we’re just trying to enable that opportunity and then to grow

Do you have any planned changes or developments ahead for you or the Gwinnett Police aviation units that are coming up?

As pilots, we’re always learning. Every day we’re just trying to enable that opportunity and then to grow. In the past, we’ve just gone to find bad guys and missing persons, but within the last two years, we’ve upgraded our capabilities. We became aerial firefighters, so we do Bambi Bucket operations. We also do aerial platform shooting, where we have qualified members in the back of the aircraft just in case we need them for an incident. And we’re starting to develop our medevac provision. If we have a downed officer or a SWAT operator, we’ll be able to extract them and get them to some kind of advanced medical care. We’re trying to expand our resources beyond just going out on missions and finding people.

How do you find these changes and adaptations to your work, and what it is about them that interests you particularly?

Two years ago, we started getting more involved with networking and meeting new people. We met Dave Callen, a retired Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Aviator who started SR3 Rescue Concepts, he did the training for our two new recruits from zero flight hours all the way up. Being able to expand our capabilities with his company was how we were able to get into firefighting, platform shooting and, now, medevac training.

It’s a different kind of flying, we don’t let new pilots start off with it. It’s our policy to have a minimum of 1,000 hours before starting that kind of training. Then you go through the courses and maintain certifications and proficiency to be able to continue to operate those missions. It’s definitely a challenge, but it is more enjoyable than just flying around looking for bad guys.

Now, we would rather have a good person on the unit and train them to be a pilot than somebody who’s already a pilot and train them to be a good person

You mentioned that your new colleagues had no flight hours, is that normal?

When I first came over to the unit, you needed a rating to get in. So, I went out on my own time and got my private rating just to be able to be considered before being accepted onto the unit. Now, we would rather have a good person on the unit and train them to be a pilot than somebody who’s already a pilot and train them to be a good person. We are a small unit and it’s not about any single person – it takes all of us to operate. When I talk to especially young officers who are on the road, they say: “I don’t think I could ever fly. I don’t have the time or the finances to get my rating.” I’ll reply: “Hold on, you don’t need that. Go out there: work hard, be a good person, be a good police officer. And when it comes time for us to send out a letter of intent, if you want to come to our unit, your chances of being looked at and possibly selected are just as good as somebody who already has a pilot rating.”

December 2023

Issue

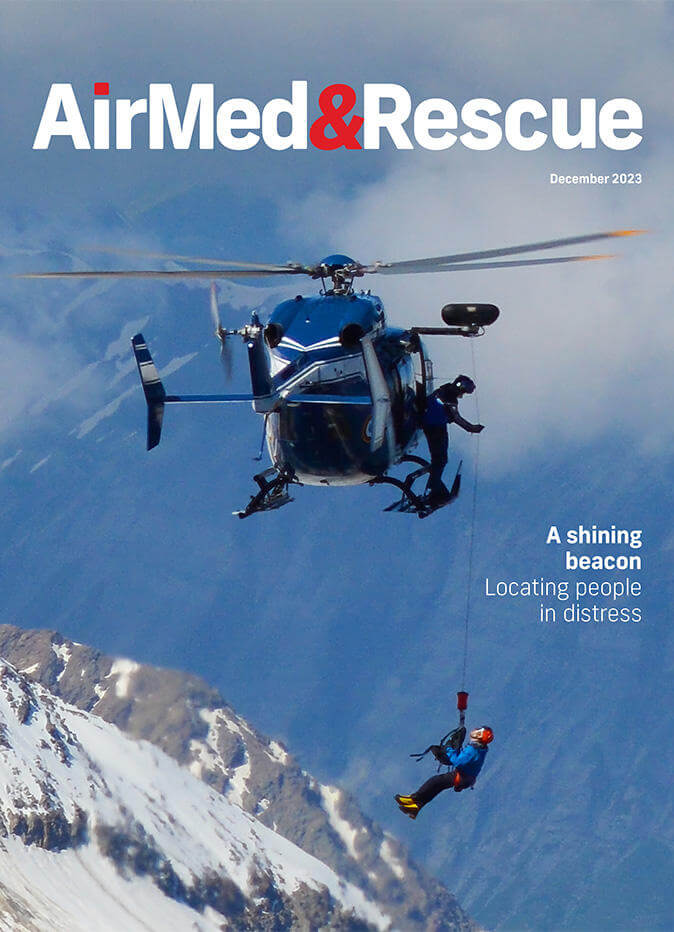

In the December edition, we cover personal locator beacons to aid with rescue; rescue operations in Mediterranean Sea; preparation for southern hemisphere fire seasons; and the value of sleep and rest for safe operations; plus more of our regular content.

Jon Adams

Jon is the Senior Editor of AirMed&Rescue. He was previously Editor for Clinical Medicine and Future Healthcare Journal at the Royal College of Physicians before coming to AirMed&Rescue in November 2022. His favorite helicopter is the Army Air Corps Lynx that he saw his father fly while growing up on Army bases.