Interview: Mark Scotland, Winch Paramedic, Bristow Search and Rescue

Mark Scotland discusses the July 2020 rescue that granted him the Royal Humane Society’s bravery award after he submerged himself underwater to support a struggling child

Can you tell us about the incident?

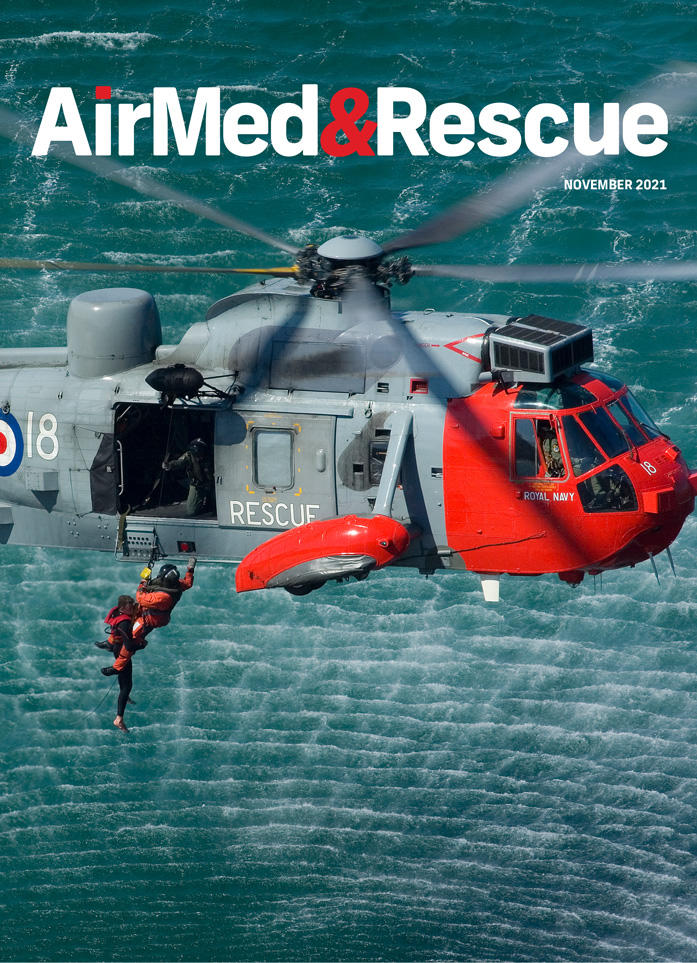

We were setting up for a two-hour training session, planning to go along the Essex coast on a navigation exercise. A couple of minutes into the flight, the call came in. When you know someone is already in the water, it’s one of the most urgent calls you can get. It was a quick rescue. The pilot took a few seconds to check the beach and, knowing I was getting into the water, I used those vital seconds to get into my kit and my equipment ready. There was a turning descent, and could see quite a few people on the beach but not so many in the water. A small girl was not far from an inflatable dinghy and her face was just above the surface. Her lips were blue and she wasn’t moving. There wasn’t a lot of wind as I was coming down the wire but the rotor wash (a vertical down wash of air turbulence caused by the helicopter blades) was starting to affect us. There was a choice of climbing higher and clearing the wash, but that meant not being as accurate with dropping me, and her condition meant getting me to her as quickly as possible. With children, we have to pay particular attention to getting the strops around them. Typically, this means pushing them away for space and I was conscious of how long she had already been under the water, so I felt it was necessary to get her on my shoulders for a moment to breathe. It wasn’t the longest time underwater – I’m probably shy of the Guinness world record by about 20 minutes! – but , even in the rotor wash, she seemed grateful and recovered enough to be coherent. After this, I had to push her away, got two strops on her, secured them, and got her out of the water.

What informed your decision to submerge yourself, or was it instinct?

It was more instinctive, but she was clearly in difficulty. You have to consider drowning and airways, their temperature, whether they’re supporting themselves. Ideally, you just want to get them out of the water, but I had to think about how affected she was – which might lead to struggling. You want to be absolutely certain about securing in a child and this can mean staying in the water a little longer. But having calmed her and letting her catch her breathe meant a few extra seconds. I could take my time to make sure those strops were secure. She’s a tough little girl. We had a report of three people in the water, but I only saw her. In the aircraft, she was calm and coherent and I was able to ask about the others and know her responses weren’t panicked or flustered. Between her and the coastguard report, we were confident there was no one else in the water. Regardless, because she had taken water in, we went straight to hospital as a lifeboat was launched to continue the search.

Is it common to be called to a rescue during a training exercise?

I wouldn’t want to put a percentage on it, but I think it is. Weather and task permitting, we’re mandated flying hours each shift to allow us to train in the various skillsets we need to be proficient in, so it isn’t uncommon to be on training when called to a rescue.

Any rescue requires the support of the entire team. How did their response change following your decision to submerge yourself?

When I’m flying with a crew, all four of us are in constant communication. They know what course of action they need to do in certain instances – the pilot got us down flying through visual reference but, at this stage, they’re reliant on the winch operator communicating through the radio. Simultaneously, the operator is responding to my hand signals and getting me where I need to be. The winch operator is also monitoring the situation at the end of the winch, the effect of rotor wash or the not uncommon instances where a rescue has panicked and tried to climb up me! The second they see I’m ready to go or I’m incapacitated, they’re keeping enough tension to make sure we can be lifted immediately.

After this rescue, when we got back to base, he was beating himself up a bit about whether we could have gotten her out more quickly. But I think he’s turned three-to-five seconds into 20. He was controlling the scene and the second she was prepared, he was ready. It’s a bit of a cliché but this is a team effort across the board. The alerting teams, rescue teams, coastguard, lifeguard, rescue boats; we all fulfil a role within it, and it’s rewarding being a part of that. Everyone involved will say the same thing, and it is immensely rewarding and flattering to be a part of that.

October 2021

Issue

- The demand for automation reveals its shortcomings meeting the human factor

- How virtual and augmented reality meets the needs of SAR/HEMS training

- Keeping critical communications infrastructure live during Hurricane Ida

- How logistics is the critical challenge of neonatal air transport

- The latest SAR equipment that pairs innovation with affordability

- Interview with Rob Pennel about the EASA South East Asia Partnership Program

- And more

Khai Trung Le

Khai Trung Le is Editor of AirMed&Rescue. He is an experienced science writer, having previously been embedded in Cardiff University College of Physical Sciences, Innovate UK research council, and the UK Institute of Material Sciences. His writing can also be found on Star Trek and Vice.