Interview: Capitán Fernando Rivero Diaz, PLM del Servicio de Montaña de la Guardia Civil

Capitán Fernando Rivero Diaz, PLM del Servicio de Montaña de la Guardia Civil, discusses the demanding training and broad remit of the Spanish Civil Guard Mountain Rescue Service with Jon Adams

How did you get involved in mountain rescue; were you interested in mountaineering before your career?

In my childhood and youth, I had some experience of life and travel in the mountains, but never with technical activities or sports, such as climbing or canyoning.

However, in March 1988, I joined the Civil Guard from the Army and, during my training at the academy, the call for the entrance exams to the Mountain Specialist Course was published. It seemed like a very attractive specialization to me, I took the exams and gained a place in a very selective course that had started with 70 applicants and ended with 23 civil guardsmen.

You’ve travelled internationally on search and rescue (SAR) operations; how does SAR differ outside of Spain?

Actually the Mountain Service (SEMON) of the Guardia Civil has only participated in two cross-border operations, both in 2015.

One operation was in Morocco, in the Uandras gorge, where the bodies of two Spanish mountaineers had to be recovered.

The other, in which I had the honor of participating, was during the search for seven Spaniards missing in the Langtang Valley, Nepal, after the earthquake of 25 April 2015 and the resulting avalanche that devastated this valley from the separation of part of a glacier.

I am also able to assess the differences with other SAR groups at international level due to our relations with rescue groups in Latin America and elsewhere in Europe, mainly from police teams.

There are different models in different countries. For instance, some Latin American police services alternate their police intervention groups in anti-terrorist actions (or with dangerous crime) with mountain rescue actions, even in some high altitude work. Whereas in European countries, almost all police forces have dedicated mountain rescue groups that carry out the missions in mountainous terrain and places that are difficult to access, including underground cave rescue. Something that differentiates police rescue groups from other rescue groups is the prosecution of certain accidents, since we are also in charge of investigating those accidents involving guides, minors, broken equipment and generally those that result in the death of a person, serious injuries or the possible involvement of a third party.

In Spain, each region has its own rescue model and – with the exception of Catalonia and the Basque Country, which have their own police rescue groups – we carry out this judicial police mission in the rest of the nation, working with the various rescue groups.

What does a typical day look like for you as a Captain in the Mountain Service of the Guardia Civil?

After 18 years operating in different rescue units (Grupos de Rescate e Intervención en Montaña; GREIMs), I am currently in charge of the Instruction and Doctrine Area of the Mountain Service and the Communication Office, reporting to the Chief Colonel of the Mountain Service.

The rest of the specialist captains of the Mountain Service are each in charge of their own Mountain Area. The national territory is divided into four Mountain Areas with between five and eight GREIMs.

The Area Chief schedules the training periods during the year and inspects the specialists of his GREIM. They are also the coordinator of the rescues where more than one GREIM is involved and of the rescue operations that are considered complex.

All GREIM and Area Chiefs collaborate with the different regional federations and mountain clubs in the prevention of accidents, with talks, training periods and the management of statistics that allow the development of effective prevention campaigns.

What sort of operations are you most regularly called out on and which ones are the most challenging?

The rescue of hikers usually comprises 52 per cent of our interventions (2022 data). Generally, it is the people with little experience who need to call on our services, and interventions of this type are not usually very complex.

However, for more technical activities, such as high mountain climbing or caving, rescues increase in difficulty. Rescues in underground caves can often last several days and require the coordination of personnel from different groups (including volunteers), and may require specialist intervention – for instance, we have specialists in micro-blasting who condition the tunnels to allow stretchers to pass through narrow passages.

What aircraft do you use for your work and how are they fitted out to aid with SAR?

The first helicopters, which have been in use since 1973, are the MBB BO105s. They have great maneuverability, but they are now becoming somewhat obsolete. Our Air Service also has some units of the high-powered MBB-Kawasaki BK117.

The helicopter in general rescue use today is the Airbus H135

However, the helicopter in general rescue use today is the Airbus H135. It is equipped with a hoist and sometimes with the EAD 01 Fast Rope bar, which is used for ‘long line’ operations.

Regarding medical equipment, in general, stretchers, splints and first aid material are carried. In some regions we also have medical personnel (doctors or nurses) from the health services of that community, who are integrated into the SAR team and who already carry more technical equipment to care for the wounded. Where we cannot rely upon medical technicians, the care of the victims is done by our SAR team specialists who have gained first aid training from the specialization course.

We have considered including a device for searching cell/mobile phones, but those currently on the market do not yet meet with our expectations.

What responsibilities does your team have beside SAR operations?

As a police force, we monitor administrative infractions that may be committed in our mountains, as well as criminal offenses.

We also support our judicial police teams in case they need to obtain evidence of a crime in places that are difficult to access.

Within our SAR missions we help coordinate searches for missing persons not only in mountainous terrain, but also in rural environments and we provide search dogs in large areas that are mainly trained to locate those who are buried in snow/avalanches.

What special equipment do you need on a SAR mission and what couldn’t you live without?

Actually, apart from clothing and traversal gear – such as crampons, ice axes, rope blockers etc – there is nothing ‘totally indispensable’ to carry out the rescue.

The fact that the Mountain Service has 56 years of experience in rescue has made us subsist with very few resources since the 1960s and mid-1970s, so we know how to do things with limited means.

That said, we will always still try to integrate everything at our disposal in our rescue operations, in order to make it more efficient and safer for the victims and for the SAR team members.

What advances in training or technology do you think is making the biggest impact on SAR, and are there any advances that you’d like to see in the work you do?

We have our own training center, and the training period to become a Civil Guard SAR team specialist involves passing a nine-month selective course.

We have our own training center, and the training period to become a Civil Guard SAR team specialist involves passing a nine-month selective course

It has been specifically in technology where we have advanced the most in recent years. Regarding the location of missing persons, this has been directed towards the location of personal cell/mobile phones. To locate people in an environment without cell coverage, there is a developing technology included as part of an application with the Spanish Ministry of the Interior (ALERTCOPS). It has a functionality for broadcasting and locating a Wi-Fi signal and is being developed by the University of Alicante, with whom we are collaborating.

The search for buried people in an avalanche with devices to search for victims in an avalanche (DVA; such as Arva devices), has improved significantly in recent years. Basically, the broadcast mechanism remains the same, but both the reception and search techniques have improved and allow the location to be found more effectively.

The adoption of new materials that increase safety in helicopter transport has made us include a training period on this subject, and the emergence of new sports modalities (such as winter canyoning), has made us study the new equipment and techniques associated to each modality.

We are currently examining the use of drones. Although the Civil Guard already has drone equipment, efficient devices for searching for missing people – such as thermal cameras, chromatography object detectors, etc – are also already well established and we hope to incorporate them into our search resources.

What piece of advice would you give to people to prevent them from getting into trouble on the mountainside, or that would help them after they do get into trouble?

It’s a very simple piece of advice, although it involves many actions prior to any type of sporting activity that takes place in the natural environment: ‘Plan all your activities well in advance’

This includes correctly studying the terrain that you are going to cover, choosing the right materials and equipment, consulting a reliable weather forecast, checking the telephone coverage in the area, identifying any bodies of water that may be in the way, and having a ‘plan B’ in the event that the scheduled activity cannot be carried out.

And in addition, carry spare equipment that you may not use, such as dry clothes in a watertight area of the backpack, a whistle, a high visibility vest, etc, just in case of emergencies.

Carry spare equipment that you may not use, such as dry clothes in a watertight area of the backpack, a whistle, a high visibility vest, etc, just in case of emergencies

What does the future hold for you and the Mountain Service?

In my case, I have four more years until I get posted to another role, but in the case of the Mountain Service of the Civil Guard generally, we just want to continue to serve in our mountains in the best possible way and to make the Spanish mountains safer.

As I mentioned before, we are adapting the technological and technical improvements that allow us to make rescues more efficient and safe. And for the last 12 years we have been collaborating with the Spanish Federation of Mountain Sports and Climbing to obtain statistics that will allow us to work on accident prevention.

June 2023

Issue

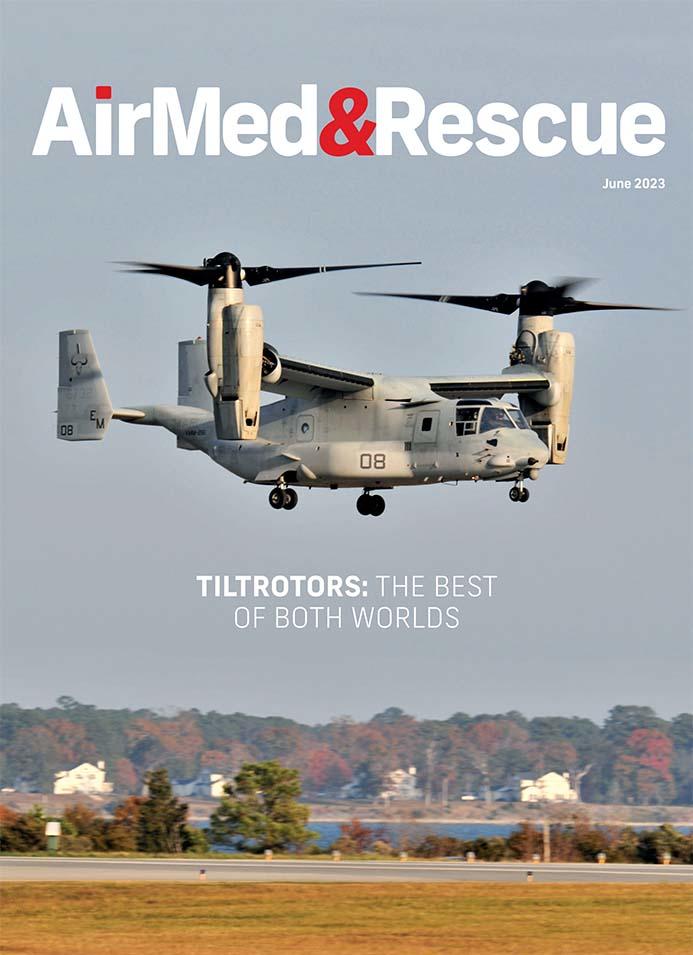

We find out about attracting the best staff; what is being done to improve sustainability; how tiltrotors compare with conventional aircraft; how rescue services approach sudden and extreme flooding; and the challenges facing MRO supply chains; plus all of our regular content.

Jon Adams

Jon is the Senior Editor of AirMed&Rescue. He was previously Editor for Clinical Medicine and Future Healthcare Journal at the Royal College of Physicians before coming to AirMed&Rescue in November 2022. His favorite helicopter is the Army Air Corps Lynx that he saw his father fly while growing up on Army bases.