Helicopter medical evacuations from Everest – too many, and at what cost?

The signals coming from Nepal are that all is not well in the local rescue helicopter industry. If commentators are to be believed, a slew of middlemen are colluding with trekking guides to put mountaineers on rescue flights they do not need and artificially inflating the bills charged to insurers, all in order to earn a commission. The helicopter operators, though, have begun to speak out. James Paul Wallis reports

In February, Nepal’s Department of Mountains restructured the fees it charges foreigners for licences to climb Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak. Discounted fees for groups have been scrapped in the hope that people will start to climb in smaller teams. The new flat fee per climber is just US$11,000, compared to a previous fee for individual climbers of $25,000; the previous group permit, which is no longer available, cost $70,000 for a team of seven climbers. Madhusan Burlakoti, head of the department, explained: “We hope to attract more climbers and also at the same time better manage the climbing teams. This will allow smaller teams and individuals more freedom when they climb Everest.”

Commentators have expressed concern over the environmental impact that an increase in climber numbers could have; Everest is already described as the world’s highest garbage dump due to the amount of food wrappers, used oxygen cylinders and discarded climbing gear littering its slopes. This could be countered by rules recently put in place that require climbers to bring all of their own gear and litter off the mountain, along with a quantity of rubbish left by previous visitors.

Another worry, though, is that if climbing as an individual or in a small group becomes more affordable, a spike in demand for guides could result in climbers signing up with inexperienced – or worse, unscrupulous – guides. Simon Lowe, managing director of Jagged Globe, a company that runs mountaineering expeditions, commented: “This will open the flood gates for anyone to say ‘I’m an expert mountaineer’, get a client and away they go.”

The prospect of poor-quality guides romping up the slopes and getting clients into situations they can’t handle is a worry. There is also the possibility here that we could see an increase in the number of guides willing to engage in helicopter rescue fraud, an issue of growing concern.

the prospect of poor-quality guides romping up the slopes and getting clients into situations they can’t handle is a worry

Fraud allegations

Emergency assistance company Global Rescue wrote in December 2013 that although only a small number of operators are involved, ‘unnecessary evacuations in Nepal have the potential to damage the climbing and trekking industry’. Earlier in 2013, an article published by the British Mountaineering Council’s (BMC’s) Summit Magazine presented details of the alleged misuse of rescue helicopters in Nepal. Although helicopters have ‘an important role to play in the inevitable rise in trekkers seeking medical evacuation’, wrote the BMC, ‘weak regulation and the chance to tap into insurance premiums have made the rescue business tempting to a new network of middlemen and agents’. According to the article, helicopter charter companies (i.e. brokers), trekking guides and agents are involved in playing helicopter operators off against each other in a search for commissions.

The BMC’s claims were echoed by Nepalese helicopter rescue provider Alpine Rescue Service, which spoke out in November 2013, saying that a number of evacuations are ‘preposterous attempts to tap into the insurance policies of clients’.

financial considerations aside, this makes flights where there is no expected medical benefit to the climber an ethical issue from the perspective of patient care

The BMC quoted an unnamed Nepali helicopter pilot, who said that if a client falls ill, trekking companies stand to make more money from the rescue helicopter kick-back than the original cost of the trek. Whereas a client might pay $1,500 for a trek in the Everest area, the company could earn twice that on the back of the flight. According to the pilot, thanks to good mobile phone signal coverage, a guide on the mountain can call up agents and charter companies, who will then haggle with a number of helicopter rescue providers to get the lowest price possible while also requesting inflated bills from the providers. Acting as middlemen, the agents and charter firms can therefore make money off the back of the flights, said the pilot, whereas the helicopter providers themselves may struggle to make a profit thanks to low margins and high insurance costs.

Another commentator, David Hamilton, one of Jagged Globe’s guides, told the BMC: “Imagine you’re a local guide leading a trek of six people for a fairly low-budget outfit. The agent will only be making $500 out of the whole deal. You’ve got someone who’s going a bit slow and it’s a pain waiting for them, you tell them they’ve got altitude sickness (mountain sickness), you call in a helicopter and your company gets 10 or 15 per cent of, what, $10,000?”

Part of the problem here is that altitude sickness can be difficult to diagnose – especially after the client has been brought down from the mountain, given that the main remedy for the condition is to descend. A doctor working at a Kathmandu clinic told the BMC that three out of five trekkers arriving by helicopter fall into a grey area where no clear determination of altitude sickness is possible. The trekkers themselves may not be in a position to assess their own conditions, either, said the doctor, who added: “If someone comes to you because you feel a bit lousy and says you’ve got to get in the helicopter because you’re going to feel a lot worse, then you get in the helicopter.” It’s easy to see why a climber might be easy to persuade to climb onboard – speaking at ITIC Global in Vienna in 2013, Mark Rands, managing director of assistance provider Specialty Group, reflected that for the amateur climber whose goal was to reach the summit, there may be little motivation for them to walk back down again.

According to Alpine Rescue Service, in some cases, the climber may not be aware that a pre-arranged agreement is in place to involve them in an unnecessary, and therefore potentially fraudulent, flight: “This agreement is set between the trip operator [and helicopter] charter companies to force the client to opt for evacuation, even at the slightest hint of mountain sickness. The victim is further convinced that the condition may worsen and thus is provoked to opt for the easy way out. Fearing the threat to their lives, the clients are then compelled to take the suggestion at hand. They are then requested to call upon their insurance/assistance companies for approval and guarantee of payment for the outrageously inflated quotes.” Such flights may also take place before insurance company approval is received, said Alpine Rescue Service, with the insurer being told afterwards that an urgent evacuation was needed to avoid risking the client’s life.

The company described a further scenario where a trip operator, a charter company and a client collude to enable the climber to knowingly partake in a ‘free helicopter tour’, under the pretence of it being a necessary rescue flight, all at the insurance company’s expense.

Impact

Where such fraud occurs, the impact on the insurers is obvious – higher or unnecessary spending on helicopter rescue flights. Alpine Rescue Service has said: “These issues need to be addressed abruptly, as otherwise, the insurance companies are bound to witness a sharp rise in their travel insurance policy claims in the near future.” The costs are passed on to the trekkers, however, through inflated premiums. For example, the BMC’s trekking insurance is provided by ACE Group, which raised premiums for a policy covering a 17-day trek in Nepal from £68.03 to £84.56 in 2013.

the climber may not be aware that a pre-arranged agreement is in place to involve them in an unnecessary flight

Alpine Rescue Service even stated in January 2014, shortly after it became an assistance partner of the International Assistance Group, that the level of helicopter rescue fraud in Nepal could ultimately lead to a fall in the number of trekkers heading for the country: “If such outrageous endeavours are not controlled and eliminated altogether, we will see the proliferation of such immoral institutions that will definitely create a large barrier for not only the insurance companies at large, but also to trekkers and climbers who want to explore and embrace the holy Himalayan peaks of Nepal.”

Along with escalating insurance premiums and a surge of claims, Alpine Rescue Service reflected that the situation could begin to tarnish the image of honest service providers. Ram Nepal, the company’s executive director, told us: “Such instances of fraud can also hamper the reputation and credibility of honest companies. Retrospectively, these attempts are also responsible towards making Nepal an expensive tourist destination as the policy prices increase, and altogether, this will lead to damage of the industry.”

It’s worth noting that a helicopter evacuation carries an element of risk – the risk of suffering injury or death should an aircraft accident occur. As with any ‘medical’ intervention, the risk should be balanced by the potential benefit to the patient. Financial considerations aside, this makes flights where there is no expected medical benefit to the climber a moral issue from the perspective of patient care. Where a trekker is duped or coerced into taking a helicopter trip they don’t need, they are being exposed to risk without a compensating medical benefit.

Action

The pilot quoted by the BMC suggested that one step insurers can take to combat fraud is to make thorough checks on the bills received for rescue flights – for example, by checking the number of hours quoted against the flight log of the helicopter involved. Another course of action is to rigorously assess the climbers. Mark Rands explained that Specialty Group works with a medical provider in Nepal to evaluate evacuees after their arrival at a clinic.

Climbers themselves can also play a part. Writing on this topic in December 2013, emergency assistance provider Global Rescue urged members heading to the Himalayas to educate themselves on the facts of altitude sickness, and to research tour operators and guide companies to understand their perspectives on helicopter evacuations in order to avoid being duped into taking a flight they don’t need.

We spoke to Shree Airlines, a Nepalese owner and operator of a fleet of helicopters that recently took delivery of the first of five AS350 B3e rotorcraft ordered last year from Airbus Helicopters. Anil Manandhar, corporate manager of the company, noted that although he has heard of the types of helicopter rescue fraud described in this article, Shree Airlines ‘is not involved in any such unscrupulous or fraudulent activities’. He added: “Which may be the reason why we are not called for medevac [missions] frequently. As a matter of policy, we will not agree to anything that we feel is unethical. I think it is one of the main reasons for our low involvement in medevac[s] brought in by some intermediaries.” In terms of how fraud can be reduced, he said: “Such activity will reduce significantly if the insurers eliminated middlemen and entered into long term contracts directly with reputed air service providers, especially ones with a strong emphasis on safety in operation.”

Ram Nepal further suggested that it might help if all operators were to insist that medevac missions be preapproved by an insurer, or be paid for upfront. This, he said, would give the climber a good incentive to only fly when necessary.

Suman Pandey, CEO of Nepal-based helicopter operator Fishtail Air, told us that his company is taking firm action to discourage fraud: “Some insurance companies have agreed to work with us together and solve this issue. In this, we are sending a doctor with every evacuation mission and if the doctor finds that client is in a safe condition, we have been told to drop the client and return with an empty helicopter.”

a number of evacuations are ‘preposterous attempts to tap into the insurance policies of clients’

Conclusion

Alpine Rescue Service has stated its goal is to ‘wipe out the contamination that has been persisting in the field of emergency medical evacuation in Nepal’. Ram Nepal emphasised that it is not the air rescue providers themselves, but rather the helicopter charter companies, tour operators, travel agencies and trekking guides, who are responsible for fraudulent evacuations: “The helicopter operators do not have any role to play in the fraud. [They] have no prior knowledge of a fraudulent evacuation and only charge their standard rates. However, these intermediaries are the ones to grab hold of a large margin which is not an honest income.”

Suman Pandey reflected that although insurance companies are affected by being made to pay exorbitantly high prices, helicopter operators are the main victims in this scam, as the actions of the middlemen lower the income that they receive. He called for insurance companies, assistance companies and helicopter operators to work together, as the current situation is unsustainable.

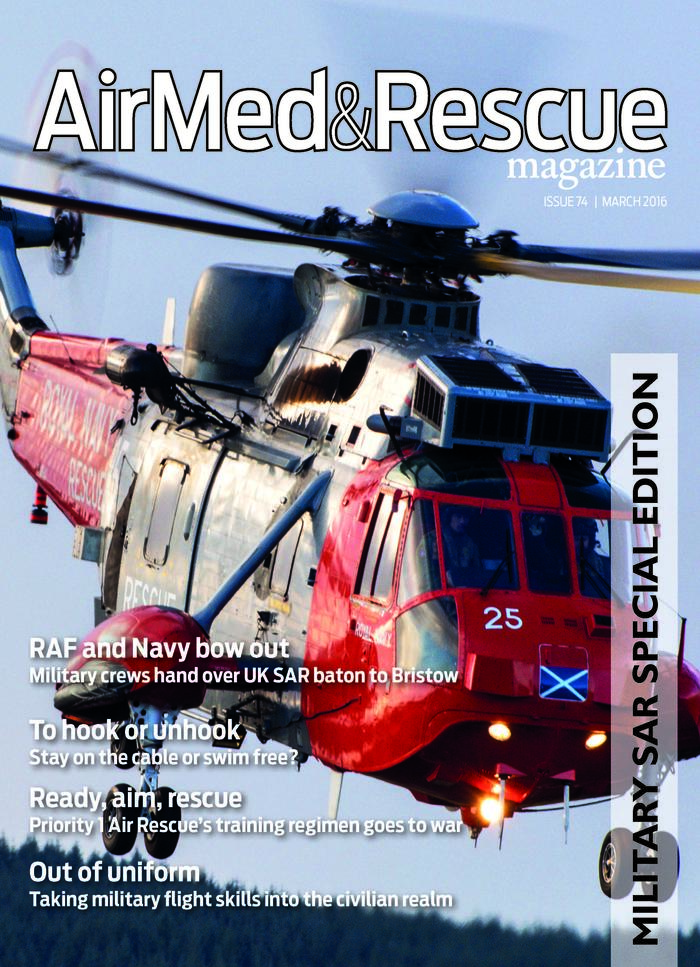

March 2016

Issue

In this issue:

RAF and Navy bow out - Military crews hand over UK SAR baton to Bristow

To hook or unhook? Stay on the cable or swim free?

Ready, aim, rescue - Priority1AirRescue's training regimen goes to war

Crew resource management

Interview: Kevin Weller, Chief technical rearcrew, Bristow Helicopters, HM Coastguard Caenarfon SAR

Aircraft Spotlight: Quest Kodiak 100

James Paul Wallis

Previously editor of AirMed & Rescue Magazine from launch up till issue 87, James Paul Wallis continues to write on air medical matters. He also contributes to AMR sister publication the International Travel & Health Insurance Journal.