Communication versus expectation – flight in IMC demands an exacting compliance

Aeromedical pilot Mike Biasatti discusses the importance of having a thorough knowledge of what to expect when flying in IMC, how to recognize when that picture isn’t developing as it should, and a confidence to question and confirm what’s happening versus what you’re expecting

US entrepreneur Jim Rohn and success coach Tony Robbins, as well as many others I suspect, have said that ‘success leaves clues’. To an even greater degree in aviation, so does tragedy. Examining those clues and learning from them is the responsibility of every aviator, professional or private, air transport pilot (ATP) or student.

In 1994, I was in Oakland, California, and I remember hearing of (and later reading) the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report of a Bell 412 EMS helicopter that, while being radar vectored for an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach, collided with mountainous terrain killing both pilots and the two flight nurses on board.

The controller responsible for issuing the approach clearance to the aircraft observed the helicopter about three miles from the airport at an altitude of 7,000ft. Even now, 27 years later, the part of the report that I’ve never forgotten was the air traffic control (ATC) supervisor’s comment. When being questioned about why the helicopter was still at 7,000ft after being cleared for the approach (and why that didn’t give cause for inquiry by the controller of the pilot), where the Initial Approach Fix (IAF) was 5,600ft and the airport elevation 2,857ft, he advised that because the aircraft was a helicopter it would be capable of going over the airport and descending vertically to land. Weather at the time the approach was initiated was 500ft broken, 3,000ft overcast, with two miles visibility in fog and drizzle.

My initial thought was that there were many breakdowns in communication, but I think it’s more precise to say that there were numerous breakdowns in understanding.

When asking for vectors the pilots said, ‘you don’t have to bring us in too close to the outer marker’. The controller replied with ‘Roger’, which he later explained had no particular significance to him, other than to acknowledge the transmission from the flight crew.

The controller vectoring the helicopter onto the approach provided a heading that wouldn’t result in it intercepting the localizer.

The controller’s supervisor thought that a helicopter could descend vertically upon arriving over an airport under instrument meteorological conditions (IMC).

This flight took place in 1994 long before the advent of moving maps and area navigation (RNAV) approach overlays. There’s no way of knowing for certain what conversation the pilots were having among themselves as the circumstances of this approach developed, but it might be fair to assume the following: that they put their faith in the controller to provide vectors, which would result in intercepting the localizer; that the controller’s ‘Roger’ to their comment about not being brought in too close to the outer marker was understood by the controller to mean what they intended it to mean; that they didn’t want to be vectored in too close to the outer marker so they would have time to get established on the localizer and lose some altitude from their assigned 7,000ft down to 4,600ft, which would provide for a smooth intercept from below the glideslope.

It’s possible that this prior assumption resulted in the aircraft paralleling the localizer, with them expecting it to come in or the controller to provide an additional vector. After some time and nearing the middle marker they corrected their heading, but by that time they were over or just passing the airport and the helicopter began descending from 7,000ft, possibly thinking they were above the glideslope and on the front side of the approach instead of now on the back side.

I’ve been on instrument flights and received, as well as overheard, what I felt were ambiguous instructions and replies from aircraft under ATC. You always read back instructions, particularly altitude changes, heading changes and approach clearances, but if you have any doubt what the instruction was, what I do is reply with ‘confirming out of 8,000ft for 6,000ft’, or 'confirming ‘right turn to 230’. That can alert the controller that you’re uncertain and need clarification. Controllers have a lot going on and are responsible for many aircraft. By alerting them with your need for confirmation, you can draw their attention back to their instruction so that you can both be certain of what’s expected.

Helicopters operating IFR in the US are not as common as in some other countries. Often, we operate at lower altitudes, on direct (off airway) routes and at slower speeds than our fixed wing brothers and sisters. If an ATC isn’t accustomed to working helicopters into the approach sequence, they will generally treat and expect you to operate as the aircraft do. As one example, an instrument approach I flew very often was the RNAV 35 into KBAZ (New Braunfels), Texas. Our flightpath was typically a direct leg to intercept the initial approach fix (IAF) at FORES at about a 90-degree angle. The approach called for an outbound procedure turn with a four nautical mile outbound racetrack-style leg. On one occasion, since we were already at the prescribed altitude, we were allowed to bypass the right outbound turn and proceed direct to the final approach fix (FAF), turning left on course. Night after night I made and received the request to bypass the outbound procedure turn, so much so that I started to drop it from my request and just continue inbound. On one unusually busy night I did as I had been doing, not knowing that the controller was fully expecting me to follow the instrument approach procedure (IAP) to the letter. He had conflicting traffic and my turn without approval caused a reduction in separation of my aircraft and another. It was just that simple. The error was mine and mine alone and serves as a humbling reminder that there are no routine flights and the need to communicate – but, even more importantly to understand what’s expected over what’s been accepted – is critical.

Flight in IMC demands an exacting compliance with altitudes, headings and assigned changes, but to an even greater degree a thorough knowledge of what to expect, how to recognize when that picture isn’t developing as it should, and a confidence to question and confirm what’s happening versus what you’re expecting. Trust, but verify.

Your place in the National Airspace System sequence is part of a beautifully orchestrated aerial ballet. ATC needs to know what you’re doing and that you’re doing what he expects so that he can keep everyone safe. Never hesitate to question and confirm ATC instructions. Human factors play a huge role in keeping us safe, and we all need to work together.

April 2022

Issue

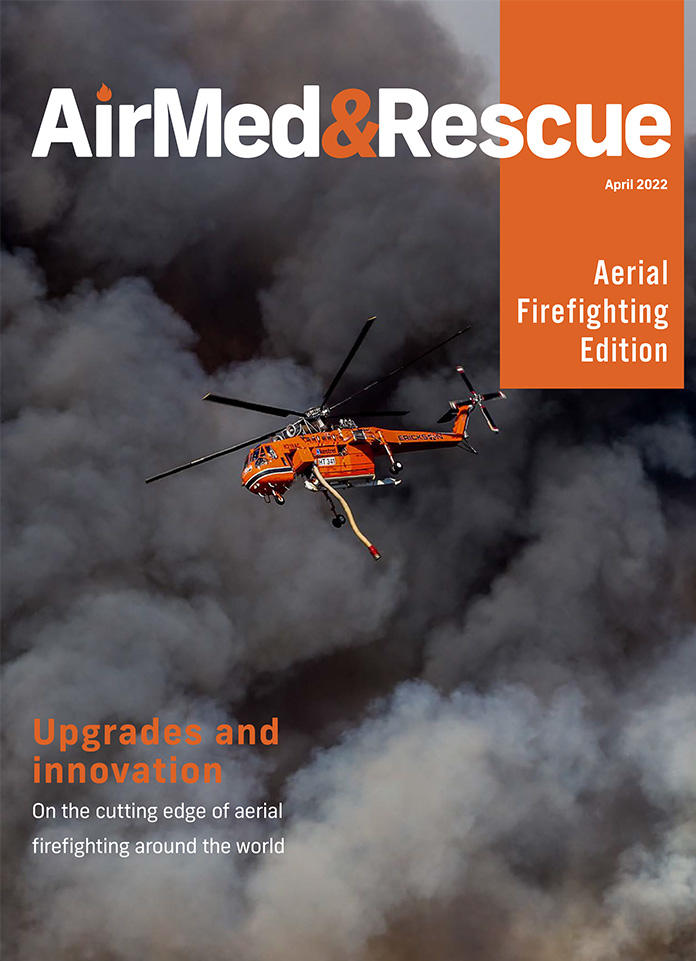

This edition of AirMed&Rescue contains in-depth analysis of firefighting aircraft and equipment innovation, the pros and cons of amphibious and land-based air tankers, using drones as fire surveillance machines, and the issue of federal versus state coordination of aerial firefighting assets in the US.

Mike Biasatti

A helicopter air ambulance (HAA) pilot in the US for 20 years and a certificated helicopter pilot since 1989, Mike Biasatti continues to enjoy all things helicopter. In 2008, the deadliest year on record in the US HAA industry, he founded EMS Flight Crew, an online resource for air medical crews to share experiences and learn from one another with the goal of promoting safety in the air medical industry. He continues to write on the subject of aviation safety, particularly in the helicopter medical transport platform with emphasis on crew resource management and communication.