The challenging world of urban police aviation

David Pearl speaks to the Los Angeles Police Department to gather its perspective on the universal challenges of aerial policing and their solutions

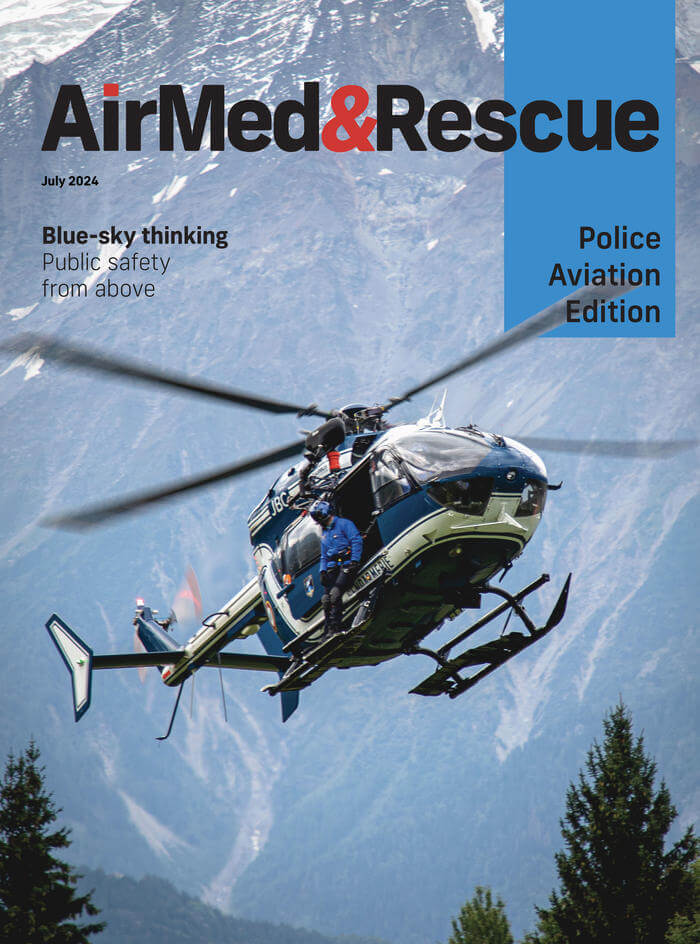

Police departments have been using helicopters since the mid-1950s. Much faster than patrol cars and able to operate above congested streets, helicopters have added an exciting and highly impactful dimension to urban crime fighting.

As technology has evolved, the capabilities of police aviation units have expanded correspondingly to the point where they have become integral components in virtually everything police are called upon to do. They confront ongoing challenges on multiple fronts while adjusting to a dynamic crime-fighting landscape, increased responsibilities and higher expectations from the public.

As this article will illustrate, police aviation units face two basic challenges:

- Technological: are the helicopters they have capable of performing the missions they are assigned? Are they fast enough, equipped with the appropriate equipment – cameras, search lights, navigation, data management, flight following and communication systems?

- Personnel: do the aircrew (pilot and tactical flight officer) have the right skill sets and experience to utilize the technology effectively and carry out the missions successfully? Is the ground support system sufficient to ensure that the aircraft and onboard systems are properly maintained, and effective procedures are in place to facilitate communication between the helicopters and police officers on scene?

The article will examine big city police aviation through the lens of the LAPD Air Support Division (ASD). First formed in 1956, the ASD, or Helicopter Unit, as it was known back then, is not only one of the oldest urban police aviation units in the USA, but one of the largest as well. Its example and experiences over nearly 70 years are representative of how large urban police departments approach the dual challenges referenced above.

The ASD commenced operations as the Helicopter Unit with one Hiller UH-12C helicopter. Two more were acquired by 1965. These resembled the helicopters used during the Korean War. Sergeant Manuel ‘Manny’ Dickerson, a senior Tactical Flight Officer with ASD, recalls that they looked like they came right off the set of M*A*S*H.

The vast potential of helicopters was obvious immediately. Their superior speed and ability to fly point to point and over or around obstacles reduced response times significantly. Figuring out the best way to utilize this new asset and transform helicopters into a powerful force multiplier, however, required decades of trial and error, technological advancements, and redefining training procedures as well as the expectations for ASD’s aircrews and ground support personnel.

The Hiller UH-12C helicopters proved to be too slow to support a wide variety of missions. Patrol officers often joked that they could drive faster than a UH-12C could fly. Additionally, as ASD’s responsibilities expanded to include search and rescue missions, and pursuing suspects in uninhabited areas at night, the need for better searchlights, camera equipment, and navigation systems became acute. The UH-12Cs could not accommodate these needs.

Evolving with new technology

ASD first addressed this need in 1968, acquiring some Bell 206A Jet Ranger helicopters. These were jet powered, significantly faster and able to carry better searchlights, cameras, and other advanced equipment, thus enhancing their mission capabilities. Further expansion took place in 1974 with an increase to 15 helicopters. The Helicopter Unit was also then rechristened the ASD. In 1976, the Special Flight Section (SFS), a unit dedicated to supporting undercover police operations, was added and ASD’s role expanded to include narcotics and serialized criminal investigations.

For 20 hours a day, two helicopters are always in the air, flying three-hour shifts

Over the ensuing years, ASD has continued to upgrade its helicopter fleet and their technological capabilities. Today, ASD operates 16 modern helicopters, including the Bell 206 B3 Jet Ranger, the Bell 412, the Airbus AS350 B A-Star, and the Airbus H125. Each aircraft is equipped with sophisticated imaging, search, communication, and data management technology, enabling aircrews to prosecute missions beyond the capabilities of the older helicopters.

Other than mechanical issues, bad weather is the only thing that keeps ASD helicopters on the ground. They must adhere to visual flight rules (VFR). Because they are not rated for instrument flight, whenever the cloud ceiling is lower than 1000ft and/or the visibility is less than three miles, the helicopters are grounded.

ASD has its own heliport, which sits atop a building in downtown Los Angeles. For 20 hours a day, two helicopters are always in the air, flying three-hour shifts. ASD can operate 24 hours a day if needed. The helicopters typically operate at 800-1,000ft while patrolling a 500 square mile area.

The ASD helicopter fleet utilizes forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera systems made by Teledyne FLIR. Brian Spillane, a senior Teledyne marketing executive, summarizes the benefits of the FLIR system as “reducing cockpit workload to facilitate focus on the problem at hand”.

Larry Krieg, Director of US Sales for Teledyne FLIR Defense, concurred: “Teledyne FLIR’s airborne sensors feature cutting-edge target assist technology, allowing operators to maintain situational awareness with minimal input, helping them to spend more time on critical mission tasks. Leveraging geopoint technology and auto-tracking software, these sensors enhance precision, and can help operators save valuable time while in the air. The latest HD optics, combined with advanced functions like geofocus, enable rapid identification of targets of interest, providing unprecedented clarity essential to their mission.”

The FLIR cameras are integrated with the helicopters’ mapping systems and significantly enhance the aircrews’ ability to track targets in virtually any environmental condition: darkness, daylight, fog, smog, rain, etc. They produce real-time, high-resolution, continually updated images that help the aircrews find persons of interest and enable them to assess whether a target is armed, and what type of weapon is involved. The cameras are also very useful in locating evidence at crime scenes.

It is not just the targets that these sensors are used for, but also to increase fields of view and situational awareness, said Krieg, particularly in a crowded urban space: “Teledyne FLIR sensors provide airborne law enforcement operators with precision optics designed to maximize fields of view and situational awareness at any operational altitude. This is key for urban areas where airspace is crowded due to commercial traffic requiring flight crews to fly high or fly low. Maintaining visibility of buildings, towers and other structures is made easier for air crews using Teledyne FLIR multi-spectral sensors. This increases not only the safety of the crew, but also provides critical surveillance capabilities during missions key to public safety.”

The mapping systems previously mentioned simplify navigation for aircrews and are a significant upgrade from printed road maps (Thomas Guides, etc.) and visual reference points. Modern mapping technology enables aircrews to utilize GPS to reach their targets by the most direct route, which reduces response time.

ASD helicopters are equipped with satellite communications (satcom) technology made by SKYTRAC, a Canadian company. Iain Ronis, a SKYTRAC executive, described the benefits of this communications technology as “reliable, real-time video and data transmission, secure, push-to-talk voice and text communication, and automatic flight following”. He added that SKYTRAC’s hardware is compact, lightweight, and easily accommodated by ASD’s helicopters.

Sergeant Dickerson endorsed satcom as providing clear, 100% reliable and secure communications, irrespective of weather or other environmental conditions that often degrade the performance of other communication systems. Additionally, the ability to pass and receive video data obtained from FLIR cameras in real time substantially improves mission performance.

Lastly, the automatic flight-following component of the SKYTRAC technology permits ground support personnel to monitor all facets of a helicopter’s performance in real time. This feature improves aircrew safety and provides real-time position, fuel status, and engine performance data. Ground personnel can report anything of concern to the aircrews, whose focus may be distracted by mission requirements.

Patrol officers first, aircrew second

As far as ASD has progressed over the years, it is still a work in progress. Nowhere is this more apparent than in how aircrew are selected and trained – the second of the dual challenges ASD has confronted since its inception.

With more helicopters and a growing range of missions, ASD needed more and better trained aircrew and ground support personnel. Its selection and training procedures had to evolve with the new technology and mission capabilities. ASD devised life-long learning programs for all personnel to ensure that their knowledge and skill sets evolved with new technology, changing mission requirements and rising expectations.

The most important quality for any prospective aircrew, pilot or tactical flight officer (TFO) is patrol experience. The two-person aircrew for each helicopter consists of a pilot and a TFO, each with at least five years of patrol experience. Sergeant Dickerson explained the rationale behind this: “If you don’t understand what the guys are doing on the ground, whether it’s a car chase, foot pursuit, missing person, or anything else, you can’t help them from the air. ASD can’t teach you how to be a good cop. You must be able to take control of a situation, to multi-task, anticipate, and stay calm. You must be confident and a good communicator. The guys on the ground must trust you, and if you don’t have enough experience on patrol, it shows, and you won’t make it as an aircrew member.”

ASD trains its aircrew in house. It is a very challenging program. Less than 30% of the candidates graduate. Tactical flight officers can become pilots and vice versa. It is essential that everyone in the cockpit understand each other’s role. This improves the team’s overall performance and capabilities. Additionally, given that every new technological development and change in mission parameters and procedures requires aircrews to adjust, ASD requires aircrew to undergo recurrent flight and ground training using simulators once a calendar quarter.

Recognizing the common bond that all aviators share, ASD conducts a week-long training course open to aviation operators from anywhere, not just those involved with urban policing. In these sessions, ASD officers share experiences, observations, best practices and other valuable information of interest to a diverse aviation-focused audience.

Aware of the complexities and attention saturation that occurs during missions, Teledyne FLIR aims to make its systems as easy to use as possible, reducing the need for overly extensive additional training. “Teledyne FLIR sensors are operated by a dedicated TFO or systems engineer in the cockpit using an ergonomic hand controller positioned in front of a tactical display. The advanced Auto Tracker feature enables the TFO to easily track vehicles and individuals. Additionally, Teledyne FLIR’s geopoint technology ensures precise pointing, allowing the system to remain focused on the scene with minimal operator input. The new 380X technology offers touchscreen control for key features, streamlining tasks and providing quick access to commands, which can make the difference during a pursuit or other critical public safety mission,” said Krieg.

If you don’t understand what the guys are doing on the ground, whether it’s a car chase, foot pursuit, missing person, or anything else, you can’t help them from the air

Looking to the future

The pace and scope of change characteristic of police airborne units such as ASD over the past seven decades likely will pale in comparison with what is yet to come. Dan Schwarzbach, Executive Director and CEO of the Airborne Public Safety Association and an experienced police helicopter pilot, predicts a future dominated by drones and artificial intelligence (AI).

“All police departments recognize the significant tactical advantages associated with airborne platforms, but only 350 to 400 out of approximately 18,000 police agencies in this country operate manned aircraft. 8,500 of these agencies now utilize drones in some capacity,” he said.

Schwarzbach observed that, while police departments already are incorporating drones and AI technology into their operations, this is just the tip of the iceberg. “We are still in the proof-of-concept stage, developing a comfort level with and trust in [them], and overcoming deep-seated fears and misconceptions.”

He likened this process to the gradual public acceptance of remotely driven trains such as those commonly used at airports. People don’t even think about them now. “We’ll get there. Big companies like Amazon already are, as they utilize drones guided by AI for package deliveries. Drone usage is exploding, and public acceptance will follow.” Schwarzbach envisions police drones situated throughout cities that launch autonomously in response to 911 or other distress calls and are guided by AI to potential crime scenes. “This will revolutionize police work,” he concluded.

Police aircrews have always embraced exacting expectations and new technology. Continuing their long tradition of excellence, the men and women who will protect and serve from the skies of tomorrow can face the future confident that they are more than equal to any challenge they will face.

July 2024

Issue

In our special police aviation edition in July, discover the considerations for urban public safety; read about the way drones are being used by the police; and discover how law enforcement agencies work with other agencies on complex operations; and find other features on treatment for major bleeding injuries; why health and usage monitoring systems are finding growth in the air medical sector; and the modification of aircraft for special missions; plus more of our regular content.

David Pearl

David is a former Navy pilot and an attorney specializing in aviation law. He defended pilots, aircraft manufacturers, airlines, and aviation businesses including several significant jury trials.

Flying and airplanes are his passion. Now a freelance writer, David writes for a wide variety of clients on range of topics.