Better together: how Babcock & Ambulance Victoria are keeping patients safe

Babcock Australasia’s Darren Moncrieff and Alex Tooms, Managing Director of Aviation and Critical Services and Pilot respectively, and Michaela Malcolm, MICA Flight Paramedic at Ambulance Victoria, outline their collaborative approach to HEMS operations

Which rotary-wing aircraft does Babcock operate? Why was this model chosen, and how has it been adapted and upgraded to ensure it is optimum for patient transport?

Darren Moncrieff (DM): Babcock Australasia’s fleet of rotary wing aircraft play an integral role in delivering world-class emergency aeromedical response, patient care, and recovery from remote and challenging environments across Australia. We are the biggest operator in Australia of the Leonardo AW139 helicopter. We operate the aircraft for Ambulance Victoria from four bases: Essendon, Latrobe Valley, Bendigo and Warrnambool in Victoria, Australia. Since 2016, we have supplied five AW139s, plus a service assurance aircraft, to support Ambulance Victoria’s Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) operations.

Our fleet include early adoption of new technologies, custom configuration of specialized on-board aeromedical equipment, as well as bespoke aircraft cabin designs and fitouts suitable for HEMS and SAR operations. The improved range that the AW139 has compared to previous models, coupled with the increase in speed, means the aircraft can quickly reach urban and remote places in Victoria, Australia from the four bases without refueling.

How are services coordinated with Ambulance Victoria and the Babcock teams?

DM: Ambulance Victoria runs its own Flight Co-ordination Centre (FCC) aircraft dispatch service from the Essendon base. Ambulance Victoria make the request for an aircraft in accordance with clinical guidelines to the FCC and the most appropriate aircraft is then dispatched.

What is the crew formation for the aircraft? When selecting your chosen crew formation, what were the main considerations you included? Can this crew formation be changed if a mission requires it, for example, if there were multiple causalities?

DM: The typical crew for standard pre-hospital and inter-hospital tasks is one Mobile Intensive Care Ambulance (MICA) flight paramedic, a pilot, and an aircrew officer. Babcock pilots and aircrew officers work in a close-knit team with Ambulance Victoria’s MICA flight paramedics. The MICA flight paramedics are highly qualified and capable of handling a range of patient issues while in transit.

The crew composition can be varied when required. Adult Retrieval Victoria tasks include the addition of a doctor during transport to attend to unwell inter-hospital patients. Similarly, pediatric and neo-natal specialists may be added for transporting children or infants. This approach to collaboration and teamwork between Babcock and Ambulance Victoria is critical when conducting operations at short notice at all hours of the day and night, often in challenging weather conditions and involving traumatic circumstances.

What makes the MICA flight paramedics stand out from other flight paramedics?

Michaela Malcolm (MM): MICA flight paramedics are specialists in aeromedical retrieval of critically unwell patients in challenging environments throughout Victoria. They work primarily on the AW139 helicopter but are also trained to work on fixed-wing aircraft. They respond to both primary response (such as major trauma) and secondary retrieval (such as inter-hospital transfers).

MICA flight paramedics provide the highest level of clinical care for Ambulance Victoria, and are able to perform interventions that include both adult and pediatric Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI), point of care ultrasound, blood gas analysis, arterial line insertion, administration of blood products, and perform chest thoracostomy. MICA flight paramedics are also trained in SAR operations, including both land and water winching.

Do the Babcock pilots and crewmen undergo any training to help the flight paramedics?

DM: Babcock aircrew officers are required to be qualified as Certificate III Paramedic Assistant. This training is delivered by Ambulance Victoria and requires Babcock’s aircrew officers to obtain practical experience in a road ambulance in order to qualify.

Do the flight paramedics undergo any flight skills training to prepare them for the environment of the aircraft?

MM: MICA flight paramedics are trained in Helicopter Underwater Escape Training and personal preservation or wilderness survival training. Babcock also provides specialist aeromedical training to Ambulance Victoria’s MICA flight paramedics, which enables them to conduct HEMS operations. This training includes down-the-wire land and water winch rescue operations in addition to their medical duties.

Is there a particularly memorable mission one of your crew could recount for our readers? Why does this mission stand out from the others?

Alex Tooms: We first received notification of the tasking from Australian Maritime Safety Authority SAR Joint Rescue Co-ordination Centre (JRCC) early in the morning. I was on shift as the Pilot in Command of HEMS2, the Ambulance Victoria AW139 based at Latrobe Valley in Victoria. Initially, the JRCC indicated that a Personal Locater Beacon (PLB) had been activated approximately 60nm North of Tasmania in the Bass Strait. At this point, the JRCC was not able to provide much more information as to what the situation was at the search location. With the rest of the HEMS2 crew, I prepared for an overwater search and potential water winch rescue operation, expecting that there might be a vessel in distress that had activated the beacon.

For the planning of the task, we were fortunate to have good weather, a reasonably calm sea, and light winds. Due to the range of the search location, we would have approximately 20 minutes on scene to conduct a rescue before a return to Melbourne, or a little bit longer with Wynyard in Tasmania as a refuel point. The crew briefed the mission based on what little information we knew, and on all the likely possibilities. We completed the flight plan, reconfigured the aircraft for the overwater search with life rafts, flares, and donned the immersion suits that we use for overwater operations in cold conditions. From when the initial call was received until we departed on the task was approximately 20 minutes.

During the flight to the beacon location, an update from JRCC confirmed that the PLB belonged to a kayaker. Whilst transiting to the search area, we were communicating over the radio with an Air Traffic Controller (ATC). The Controller used transiting commercial aircraft, Virgin and Qantas, to both relay communications to us as well as to update the PLB location that they were receiving on their aircraft.

On arriving at the search location, the weather conditions made it challenging to identify the kayak. The use of the Direction Finding (DF) equipment on the aircraft to the PLB meant that we were able to locate the kayaker within 5-10 minutes on scene. Once overhead, we could then see that the kayak had overturned and there was a person in the water holding onto it. We prepared for a winch rescue, and lowered the MICA flight paramedic down to the ocean’s surface. The kayaker was placed into a rescue strop and they were both winched back into the aircraft. The paramedic assessed the patient’s injuries in the aircraft, and identified that the survivor’s was very cold and his hands were lacerated.

Once the patient was secured to the stretcher in the aircraft, we departed the search location for the 15-minute flight to Wynyard. Local ambulance and police were waiting who then transported the survivor to the local hospital. The whole operation from departure of Latrobe Valley to Wynyard was approximately two hours.

This task stood out for a number of reasons; the initial lack of information lead to the crew having to plan for multiple scenarios. Excellent co-ordination between ATC, our aircraft, and civilian airline traffic meant that the time taken to locate the individual was drastically reduced. The survivor said he was planning a solo crossing from Tasmania to Victoria. Sometime after midnight he fell asleep from exhaustion and his kayak subsequently rolled. He was unable to right himself and could only get out and hold on to the side of the kayak. Without his PLB he would most likely not have been found. The overarching reason this mission is memorable is because through teamwork and effective planning, the crew found a lone person in the middle of the Bass Strait in distress, whose life was in critical danger.

August 2021

Issue

In this issue:

The Frisco Three’s journey to safeguard crash survivability and resolve loopholes in FAA regulations

How technology innovation and new materials are changing the test pilot role

Line operations safety audits in live combat aeromedical evacuation

The cockpit equipment keeping pilots safe

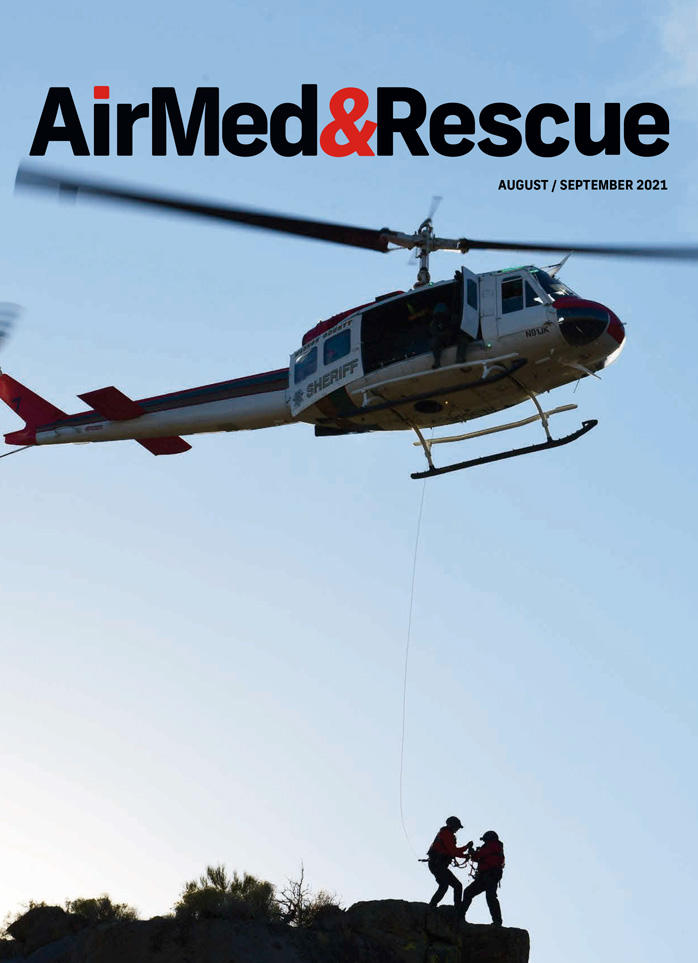

SAR innovation by necessity across three US states

An interview with London’s Air Ambulance Charity’s Dr Mike Christian

Provider Profile: Babcock Australasia and Ambulance Victoria

And more

Mandy Langfield

Mandy Langfield is Director of Publishing for Voyageur Publishing & Events. She was Editor of AirMed&Rescue from December 2017 until April 2021. Her favourite helicopter is the Chinook, having grown up near an RAF training ground!