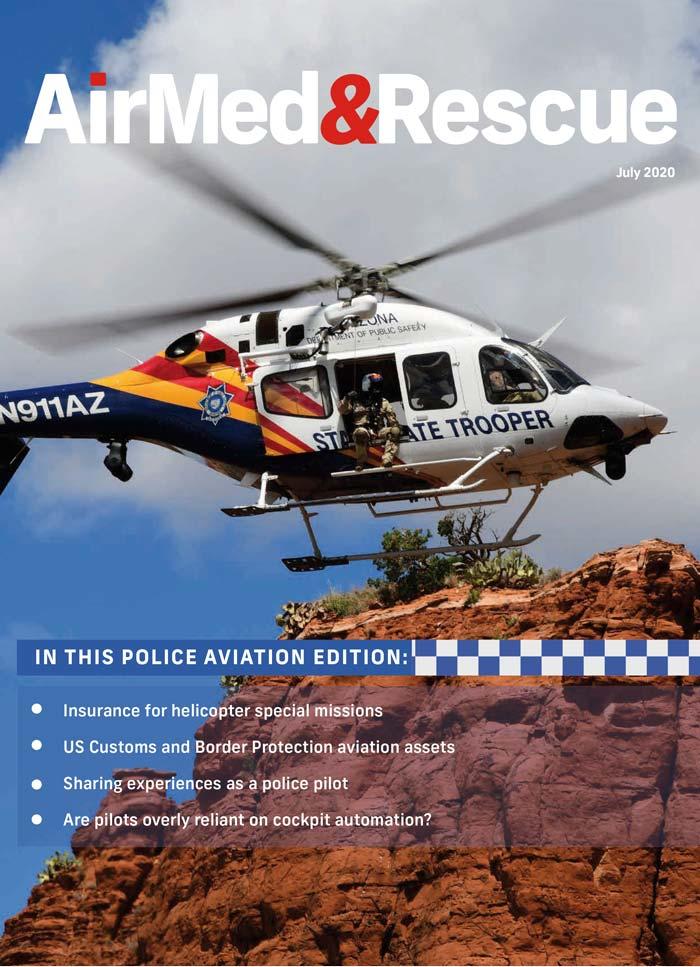

Aerial assets of US Customs and Border Protection

A border is more than a wall, a fence, a divider or a boundary line. Amy Gallagher found out how the US Customs and Border Protection and Air and Marine Operations agencies work together to effectively police borders, as well as operating an EMS program

While the United States Border Patrol (USBP) has changed dramatically since its inception in 1924, its primary mission remains unchanged: to detect and prevent the illegal entry of aliens into the US.

At the nation’s more than 300 ports of entry, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers have a complex mission with broad law enforcement authorities tied to screening all foreign visitors, returning American citizens and imported cargo that enters the US. Along the nation’s borders, the USBP and Air and Marine Operations (AMO) are the uniformed law enforcement arms of CBP, responsible for securing US borders between ports of entry.

Today, with more than 60,000 employees, US CBP is one of the world’s largest law enforcement organizations and is charged with keeping terrorists and their weapons out of the US while facilitating lawful international travel and trade. Under CBP, as an agency, may be found the following component Offices:

o United States Border Patrol (USBP)

o Office of Field Operations (OFO)

o Air and Marine Operations (AMO)

- All three internal Offices are staffed by agents and officers who are the “uniformed law enforcement arms” of CBP, not just BP and AMO.

- OFO is comprised of highly trained Customs and Border Protection Officers who are armed as frontline officers.

Domain awareness: detect, monitor, track

Domain awareness for land surveillance includes situational awareness co-ordination with the USBP to enable the detection, identification, classification, and tracking of land threats using a variety of capabilities. “Situational awareness is a more comprehensive understanding of a domain; it fuses domain awareness with information and intelligence that provides a detailed overview of the operating environment,” said Dennis Michelini, Executive Director, Operations, US CBP-AMO.

Both domain and situational awareness are critical elements in AMO’s ability to successfully execute the surveillance continuum of predicting, detecting, tracking, identifying, classifying, responding, and resolving threats, he explained.

“Knowing the domains and an awareness of the domains within a well-described vision, to assess and identify the threats, then identifying yourself within your responsibilities and skill set, combined with the situational awareness and co-ordination to execute the mission is a big area of law enforcement in what we do,” explained Michelini.

Extended border and foreign operations

AMO’s extended border and foreign operations include US and foreign government partners. This mission area involves detecting, identifying, classifying, tracking, and interdicting targets and exploiting signals in the source and transit zones while conducting combined and joint operations, such as missions conducted in the Western and Southern hemispheres.

These operations foster partnerships with foreign governments and collaboration with foreign law enforcement operations.

“Transitioning to a rescue mission using the UH-60 and responding to any kind of operation can happen at any time,” said Michelini. “We are in a transitioning state all of the time."

We are in a transitioning state all of the time.

Having been with the CBP for 25 years, Michelini’s second position with the CBP, after serving as a border agent, was in his role as an Air Interdiction Agent (AIA) pilot, where he was trained at the AMO NATC in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Here, he participated in records review, structured interviews, an oral examination and practical flight evaluations, requiring 1,500 flight hours, 250 hours of pilot-in-command, 75 hours of night flying, 75 hours of instrument, followed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) First Class 1 medical certificate following his ratings in a rotorcraft helicopter with instrument.

In his former position as an AIA pilot flying the Airbus AS350 A-Star, Michelini described one situation when he was flying about 100 feet from the ground in a deserted area. “As I flew over the terrain, I noticed an injured man on the ground,” he said. “I got on the radio to request immediate aid and brought the man to safety. I learned later that he had survived the night after a gang fight from the day before.”

AMO fleet

The CBP AMO holds a large aircraft fleet covering the US borders and in drug transit zones in Central and South America, said Michelini. Within the CBP AMO agency, the fleet of rotor, fixed and unmanned aircraft also includes the AS350 A-Star and the EC120, and the agency will take delivery of 16 new H125 helicopters later this year for patrol and surveillance capabilities.

“Our teams are proud to build helicopters right here in the US that play a critical role in protecting our country,” said Romain Trapp, President of Airbus Helicopters, Inc. and Head of the North America region. “For many law enforcement and parapublic agencies, the H125 has become an indispensable tool in the air to support operations on the ground.”

Among the CBP AMO fleet’s fixed wing assets, the CBP AMO aircraft includes the Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion Airborne Early Warning (AEW) and the P-3 Long Range Tracker (LRT).

The P-3 LRT aircraft are high endurance, all-weather, tactical turbo-prop aircraft primarily used to conduct long-range aerial patrols and surveillance missions along the US borders and in drug transit zones in Central and South America. CBP’s AMO operates the P-3 LRT and AEW aircraft, which perform a wide variety of operational missions, especially those that require long station time overhead, hemispheric range, and missions throughout all weather and environmental conditions. The P-3 LRT aircraft often fly in tandem with the P-3 AEW. Deployed in this manner, the P-3 AEW detects and tracks multiple targets and the accompanying P-3 LRT intercepts, identifies, and tracks those targets.

In 2019, Astronautics Corporation of America agreed to update the CBP agency’s AMO fleet of Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion turboprop maritime surveillance aircraft with new primary flight and navigation displays. The purchase order, which was submitted by Lockheed Martin, included upgrades for both CBP P-3 Orion variants.

Each of the CBP’s 14 P-3 aircraft will receive Astronautics’ AFD 6800 electronic flight instrument system (EFIS), including four modern six- by eight-inch digital multifunction displays, wiring harnesses, and additional spare displays for maintenance and repair. The four liquid crystal display (LCD) screens will be split into pairs of primary flight displays and navigation displays for the pilot and copilot.

Photo by Astronautics

AMO: In the field

Norman Montgomery, Director, Tucson (Arizona) Air Branch, holds a different set of challenges on the field level, maintaining a constant posture of readiness while managing ongoing daily missions. The crux of that readiness is in the training realm, both the initial and the recurrent training. At the Tucson Air Branch, initial training is priority one, said Montgomery.

“Our pilots and crew members conduct hoist and rescue operations with law enforcement responsibilities first and foremost,” he said. “The CBP AOM is a law enforcement mission which requires personnel with medical training. Many of our EMTs and critical care paramedics volunteer their medical services while serving their law enforcement duty as required.”

Although relatively new to hoisting, the CBP ensures standardization as the focal point of training.

“The last few years, we’ve conducted initial hoist training and rescue operations, which is a three-week program at our Tucson center,” said Montgomery. “While we maintain a constant training program in Tucson, we also train in San Diego, Miami and Puerto Rico, where we may have potential aircraft going to one of those areas for a natural disaster or humanitarian mission.

We may just need to send our pilots; not every rescue requires a UH-60 or hoist.

We may just need to send our pilots; not every rescue requires a UH-60 or hoist.”

“For example, for Hurricane Maria, we deployed a C-17, followed immediately with three additional aircraft,” he said.

With a strong and established skills set in rescue entities, the CBP AMO boasts a large and robust instructor pilot program. “We are essentially cross training our pilots to incorporate three different designations to increase hoist capabilities and abilities,” said Montgomery. “We do not operate like an air ambulance, but we are fully trained and capable with professionally-trained pilots.”

To maintain and monitor requirements, the CBP AMO is implementing and introducing new technologies. “We are taking delivery of UH-60 Lima to Tucson complete with increased technology in avionics and navigational capabilities and flight management systems, which are changing rapidly, with moving map systems, and infrared systems,” he explained. “We’re on the forefront of those initiatives,” Montgomery said.

AMO’s emergency medical service

As program manager of the Air and Marine Emergency Medical Service (AMEMS) program, Michael Naujoks ‘seconded the motion’ with his colleague Montgomery regarding the greatest challenge of overseeing AMO’s EMS Program: maintaining a constant state of readiness. “The collateral duty of the ‘EMS world’, combined with the responsibility of a constant state of readiness, is challenging,” said Naujoks. “It is a very large responsibility to hold. We are in a unique position in any category to transition immediately,” he added.

“Our training emphasis is on the law enforcement agent, not practising medicine such as [is done in an] air ambulance,” he added. “Our agents hold a wide range of skill sets.”

A secondary challenge is fostering relationships with the local and state medical communities requiring intentional and focused communications.

How to maintain the proficiency requirements in medicine is another challenge overcome by ‘building bridges’ within the communities, the cities, said Naujoks: “We’ve strategically addressed that need by partnering with local EMS agencies to provide comprehensive services in any mission,” he said. Maintaining proficiencies while maintaining relationships is a ‘win-win’.”

“Our agents conduct ride-along missions at local hospitals and EMS communities,” he explained. By introducing programs such as this, crews’ exposure to better medical practices is enhanced. When making calls with the hospitals’ doctors and nurses, the relationships with agents are strengthened. “We have a great rapport with our aviation crews and EMS professionals," concluded Naujoks.

We have a great rapport with our aviation crews and EMS professionals

Local communities are extremely supportive knowing the relationships benefit the entire community, he added.

“Although AMO does not specifically seek pilots with medical experience, they are more than welcome to apply and join our ranks,” said Naujoks. “We are not an air ambulance service; flying is our primary mission. It is a unique position in any category to transition immediately to a national service security event, natural disaster or a humanitarian crisis. When we are activated, we immediately identify mutual aid by state and local officials who provide the mutual aid requested, including medical.”

July 2020

Issue

In this Police Aviation issue:

Provider Profile: San Diego Police Department Air Support Unit

Aerial assets of the US Customs and Border Patrol

The cost of special missions insurance

Sharing experiences and CRM as a police aviator

Automatic reactions: When technology isn’t an asset

Multi-agency management: Designing, creating and building a response system

Case Study: AirLec Ambulance

Interview: Cameron Curtis, AAMS President and CEO

Amy Gallagher

Amy Gallagher is an internationally published journalist covering aviation, rescue, medical and military topics, including evidence-based research articles. As a journalist by education and certified English instructor, Amy has worked in both agency and corporate communications, providing educational and promotional writing and training services through her agency, ARMcomm Writing & Training, www.ARMcomm.net.